Going back in time, I discovered that the first-ever crime fiction hero was a Vizier called Ja’far, as told by Scheherazade in One Thousand and One Nights. In this story, a fisherman found a big chest floating in the Tigris River. He took it to the Caliph, and when he opened it, he discovered it contained the body of a young woman, cut into nineteen pieces. In true Arabian Nights style, Ja’far was told by the Caliph to solve the crime or else get put to death within three days. That crime ended up being solved when the murderer came forward at the last minute and confessed to his deed.

As a reward for his superb detecting skills, the Vizier was given another crime to solve and another three-day time limit to do it or be killed. By chance, he discovered an important clue that allowed him to solve the crime through reasoning, and save himself once again from certain death. I’m not sure if he was given yet another case to solve after that, but I think this story is interesting because it’s the only incident I know of anywhere in fiction where a Vizier has ended up being a hero.

Usually, as soon as you hear the words Grand Vizier, you know for sure he’s a villain and he is shortly, and without fail, going to commit a series of dastardly crimes involving hidden serpents and poisoned sherbet and turbanned thugs wielding scimitars. The role of the Vizier has definitely evolved as far as crime fiction is concerned, and so have the roles of heroes and villains right here in South Africa.

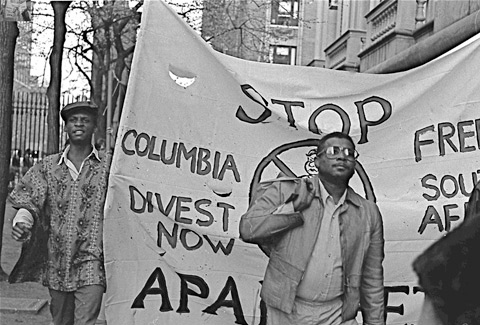

The end of apartheid has had one very important benefit for crime fiction characters. It’s levelled the playing field, and given everybody the same license to be good or evil – it’s created far more of an equal-opportunity country in that way.

Books are still written today featuring Nazi war criminal villains who have somehow managed to live in hiding and go unpunished for decades until their past evils catch up with them. The same thing is happening here today in South African crime fiction with regards to the apartheid regime. Some villains have their roots buried in its rotting carcass, while some stories are set in that era.

Flawed, wicked characters have always fascinated me. I must confess that when I have to kill a villain off in one of my own books I grieve for them, really I do, even if they were psychopathic murderers who cut their victims up into nineteen pieces. But it’s wonderful to have such a wide field of races, cultures, personalities and backgrounds to choose from when creating another one.

However, when a South African crime writer sits down to dream up the cast of heroes and villains for their next book, they must bear in mind that although apartheid is officially over, it is not yet entirely dead. It exists in the minds and attitudes of many people from all walks of life, and its legacy is still affecting our society today. So as a post-apartheid writer, I have to take this into account when creating my characters, whether they are good or bad. I don’t have complete carte blanche; I am bound by a set of unwritten rules that dictate each character must be a plausible product of the society they come from, with a background and a set of belief systems that will not seem out of place.

Where I think it gets interesting is that South Africa’s apartheid history has allowed writers to create more complex characters that combine elements of good and evil in a way that everybody can now understand better. They’re either flawed heroes in the very best traditions of Greek tragedy, or they’re sympathetic villains. I’d like the reader to think: if I had grown up in those conditions, would I have turned out any differently?

My series heroine Jade de Jong is as flawed as the best of them, being a killer who is capable of cold-blooded murder. Her redeeming qualities—I hope—are her strong sense of justice and her compassion, particularly for those who are not in a position to be able to defend themselves.

The good news is that having South Africa back on the world stage means that crime fiction writers in this country can write a compelling story for an international audience as well as a local one without having to turn our books into struggle literature.

Jassy Mackenzie is the author of The Fallen (Soho Crime, April 2012), the third installment in the acclaimed Jade de Jong investigation series set in contemporary South Africa. In 2008, the South African edition of Random Violence—the first book in the Jade de Jong series—was shortlisted for Best First Book in the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, Africa region. In 2011 the Soho Crime edition was nominated for the Shamus Award. Mackenzie now lives in Kyalami, near Johannesburg.