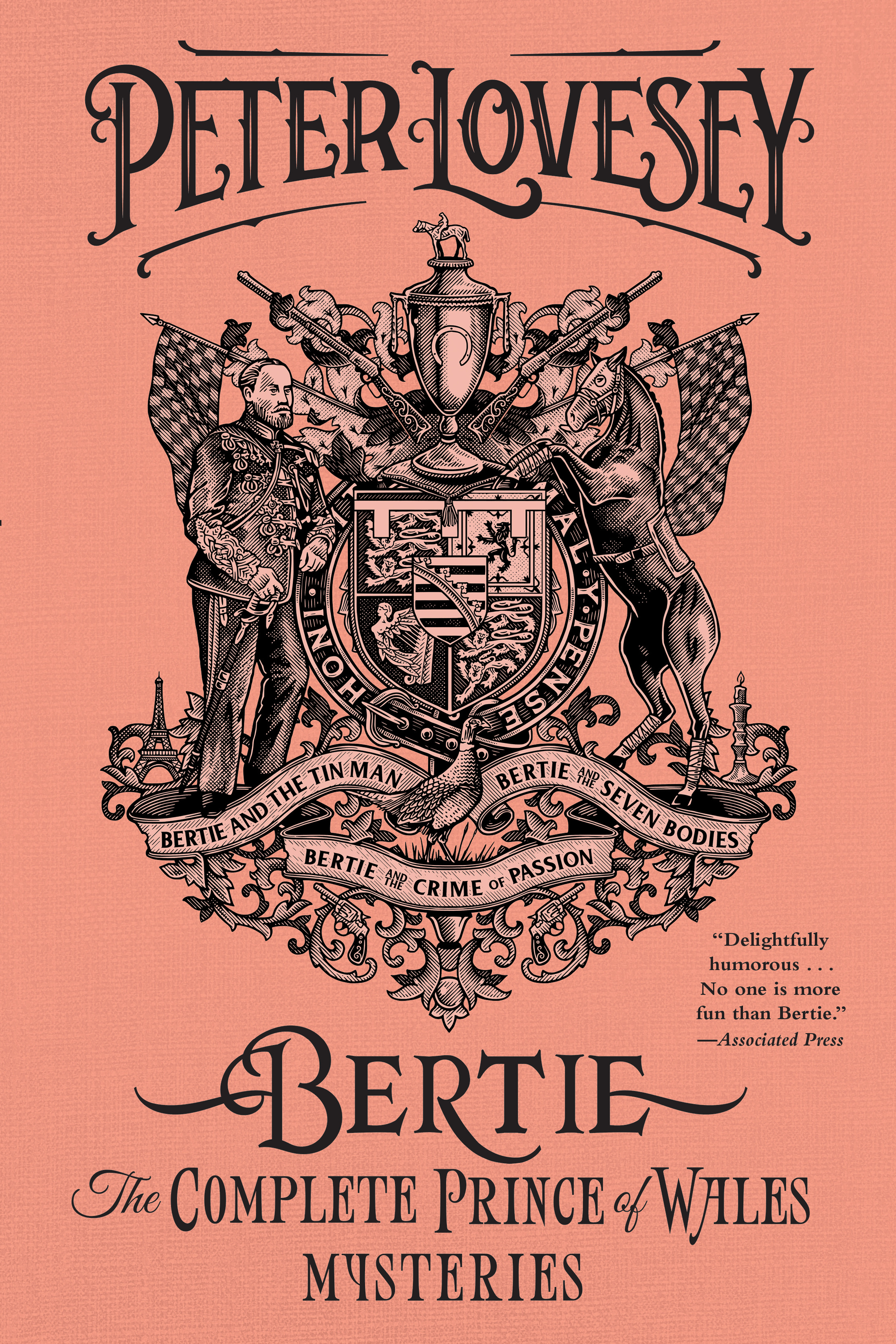

The detective memoirs of Bertie, the Prince of Wales, appear here as a single volume for the first time and I was asked to explain how this self-appointed sleuth arrived in my writing life and took over.

My career as a crime writer began with eight novels featuring Sergeant Cribb, a Victorian policeman who, unlike Bertie, was pretty good at the job. Each story unfolded against a background of some Victorian sport or pastime and I immersed myself in accounts of go-as-you-please races, bareknuckle boxing, the music halls, séances, river trips, the seaside and waxworks. A TV series was made and my wife, Jax, and I wrote a further six plays featuring such events as a wedding, a school reunion, Christmas carol–singing and the London Zoo. TV was a wonderful boost, but it quickly used up my stock of ideas for future books. Worse, I found that the characters I had in my imagination had been dulled by the power of the TV images and the brilliance of the acting. I wrote no more Sergeant Cribb novels.

Nine years later, I came across a book about Fred Archer, the foremost jockey of the nineteenth century, the rider of more than 2,700 winners. At the high point of his career, aged 29, he spoke his last words—“Are they coming?”—put a gun to his head and killed himself. Any crime writer would find such a scenario irresistible. Why did poor Fred do it and who were the mysterious “they”? Horse racing was a sport I hadn’t considered as a setting when I was writing the Cribb series. How about writing a Victorian version of a Dick Francis thriller? But I couldn’t see Sergeant Cribb as the protagonist. I needed a new detective.

The largest wreath on Archer’s coffin when it was driven through Newmarket to the grave had been from his royal patron, the Prince of Wales. In one of those lightbulb moments I pictured Bertie as my sleuth. There were clear advantages to having the future king on the case. Obviously, he must have taken an interest in the mystery. He could call on Scotland Yard for help if needed. Equally he had the power to send them packing. He knew about racing and he had limitless time to devote to an investigation. But would he be any good?

Probably not.

At this stage of his life, in 1886, he was 45, more renowned for indulgence than intelligence. He had a sense of his own destiny and a liking for ceremonial affairs, but his mother, the queen, denied him the opportunity of reading state papers and he frittered much of his life away in gambling, shooting game and being unfaithful to his long-suffering wife, Princess Alexandra. I couldn’t imagine him as a serious investigator, but he would relish the chance of playing private detective.

Bertie as an inept sleuth intrigued and inspired me. This would be his case and his book and his voice would tell the tale. Up to then I hadn’t written a book in the first person. Already Bertie was taking over.

I promised myself I would portray him as truthfully as I could, allowing that there was no evidence he had ever investigated a crime. The scandals, the mistresses and the gambling, were well-known. But the qualities that eventually made him a successful king were evident as well. He was confident, good-humored, a fine organizer and far more forward-thinking than his mother.

I still have a thick file of all the notes I made on Fred Archer. I travelled to Newmarket and saw the section devoted to Archer at the National Horse Racing Museum and photographed the silver revolver that fired the fatal shot. I visited Falmouth House, where the suicide took place, and I walked the funeral route and found the impressive headstone. The events of 1886 became more immediate to me. I wanted as far as possible to do justice to the memory of the tragic jockey. I would devise a fictional plot that worked within the constraints of the real events of a century ago.

There were enough strong individuals around Bertie and Archer in real life to allow me to involve them in the plot rather than creating imaginary characters. And I would set the story in real places. If the events came to life for me, I reckoned my readers were more likely to believe in them.

My working title was Are They Coming? But by the time I had written the book I wanted something closer to the jovial heart of the story. Fred Archer had been known to the racing public as the Tinman because he was said to have been careful with his money. I opted for Bertie and the Tinman.

The book was enthusiastically received. The quote that pleased me most was from Peter Grosvenor in the Daily Express: “It’s Dick Francis by gaslight.”

I hadn’t thought about writing a sequel until a review came in from Marilyn Stasio in The Philadelphia Inquirer: “One doesn’t wish to put that nice Sergeant Cribb out of a job; but we can’t wait to go out on another case with dear Bertie.”

Nothing as ready-made as the Fred Archer tragedy suggested itself, and I wrote another book set in 1946 and called On the Edge before returning to Bertie. The inspiration this time was the Queen of Crime. I knew the centenary of Agatha Christie’s birth would be celebrated in 1990. Like most other crime writers, I admired the audacity and ingenuity of her plotting. A whole group of her books featured lines or themes from nursery rhymes: Three Blind Mice; Hickory Dickory Dock; One, Two, Buckle My Shoe; Five Little Pigs; A Pocket Full of Rye; Ten Little Indians and Crooked House. In tribute perhaps I could devise a Bertie story using a well-known rhyme.

I was lucky to find one that the prolific Agatha hadn’t used. It was the rhyme beginning Monday’s child is fair of face. Suppose I substituted the word “corpse” for “child” so that the next line would be Tuesday’s corpse is full of grace. And so on, through the days of the week. The next step would be to plot seven murders that fitted the predictive words of the verses. The setting was ready-made: a stately home; and the occasion a house party of the kind Bertie regularly dignified with his presence. Happily for my plan, Agatha Christie was renowned for her country house murder mysteries.

I planned the book carefully. Early on, it became obvious to me that the characters—seven of whom would be murdered—couldn’t be based on real people. But I would make sure that the setting (I’d better not say which house and estate I portrayed) was accurate and the social conventions of a shooting party were followed.

Well, I finished in good time for the centenary. I was vice-chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association that year and we held our annual conference at the Grand Hotel, Torquay, and visited Greenway House where the great writer had lived. A huge banquet and fireworks display was hosted by Agatha Christie Limited at the Riviera Centre and among the guests were the actors Joan Hickson (Miss Marple) and David Suchet (Poirot). Bertie and the Tinman was published to quite a fanfare from the press.

And—would you believe it?—not a single reviewer picked up on the fact that Bertie and the Seven Bodies was intended as a nod to Agatha Christie. I felt much the same as Bertie when his best intentions had misfired.

Three years went by. I busied myself with a new character, a modern policeman called Peter Diamond, the head of CID in the city of Bath. This was a departure. Up to then, all my crime writing had been set in the past and I wasn’t entirely confident I knew enough about police procedures to embark on a contemporary series. Diamond resigned at the end of The Last Detective and became a freelance sleuth on a mission to Japan in Diamond Solitaire. Both books were popular and the first won the Anthony Award, yet I couldn’t see a way forward. Diamond was no amateur. He had hit the buffers.

I heard the call of Bertie again. He was an amateur, of course, but on his own terms.

Pumped up, I wrote the third book of the series, Bertie and the Crime of Passion, set in Paris in 1891. The Prince had a great partiality for France and visited there as often as possible. As early as 1881, he had paved the way for the Entente Cordiale by meeting the French statesman Léon Gambetta at the Château de Breteuil and discussing an alliance between the two countries to oppose Germany’s imperialism. Twenty-three years later, as King Edward VII, he insisted against the advice of the British cabinet on making a state visit to Paris that boosted Anglo-French relations and undoubtedly helped the politicians on both sides of the Channel to sign their famous declaration of 1904. In the years between, he achieved some ententes in private with the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt. Bertie’s love of Paris and the ladies of France was the inspiration for the new novel.

This one wasn’t to be a story of serial murder. Most of the characters were survivors, so Bertie was able to interact with some of the people who really did frequent the Moulin Rouge: Louise Weber, known as La Goulue, and her partner, Jacques Renaudin, known as Valentin le Désossé, and the artist Toulouse-Lautrec. He would also lock horns with the celebrated detective Marie-François Goron, chef de la Sûreté. If I say more this will turn into a spoiler instead of an introduction.

That’s enough of me. Bring on Bertie, the sleuth who outwits Scotland Yard and the Sûreté and is at least the equal of Hercule Poirot—if he is to be believed.

Read more from BERTIE: THE COMPLETE PRINCE OF WALES MYSTERIES

~

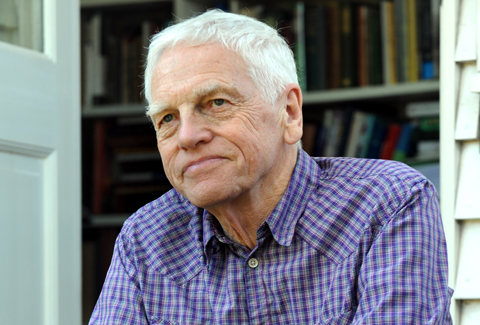

Peter Lovesey is the author of twenty-six highly praised mystery novels and has been awarded the MWA Grandmaster Award for Lifetime Achievement, the CWA Gold and Silver Daggers, and the Diamond Dagger for Lifetime Achievement, as well as many US honors.