A few weeks ago when I was in the UK for the CWA Daggers ceremony I took advantage of a free weekend to fly to Northern Ireland and impose upon Stuart Neville, his brilliant and forbearing wife, Jo, and their two adorable kids.

I first met Stuart long before I worked at Soho. (In fact, he was one of my personal references when I started here as the crime editor back in 2010.) I’d already read and loved his first novel, The Ghosts of Belfast, for its incredible story and especially its main character, Gerry Fegan, an ex-paramilitary hitman on the Catholic side of the Northern Irish conflict (the Troubles). Gerry is a hard man who was by no means a nice man and yet whom you, the reader, love to root for.

I can’t really tell you just how excited I was to see in person the places Stuart had brought to life in his fiction. Stuart knew he only had about 6 daylight hours to show me Belfast, but he made those hours count. The black taxi tour through downtown Belfast was one of the most memorable travel experiences of my life.

Our black taxi tour guide, Joel, and Stuart in front of a Shankill mural

We met our black taxi tour guide, Joel, near St. Anne’s Cathedral in downtown Belfast at 1pm on a Saturday afternoon. The first place Joel took us was the Shankill, the heart of historically working-class Loyalist west Belfast.

In the Loyalist Shankill, Dutch Protestant King William of Orange’s 1690 defeat of Catholic King James II at the Battle of Boyne is a proud historical turning point. (Hence the Orange Order, and the political significance of the color orange in Ireland, etc.)

It is a neighborhood of long row houses lined by narrow grassy lawns through which we saw children running. It is also famous for being the organizational center of such Loyalist paramilitary groups as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), both of which would eventually be formally classified as terrorist organizations. (As, of course, would the “other side,” the Provisional Irish Republican Army, often called the IRA or the Provos.)

Jackie Coulter was a UDA hero who was killed by a rival Loyalist faction in 2000, a reminder that even after the Good Friday Agreement the legacy of paramilitary violence didn’t just disappear magically.

Over the course of the tour and Joel’s illuminating narrative (he was born and bred in the Shankill himself), I was forced to realize how soft my knowledge of the actual history of the Troubles was–knowledge based, embarrassingly, on such vague and unhelpful pop culture masterpieces as the 1997 movie The Devil’s Own. (Heads up, folks, in case you’re thinking of going out to rent it: it manages to include all of *zero* explanations about what the conflict is or why anyone is involved in it. It’s actually almost amazing how the movie manages to sidestep its own core issue so entirely. Kudos, Hollywood.)

I’m going venture to say most Americans are probably pretty much in my boat: they have a concept that there was some bad blood between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, and that there was some low-grade terrorism and civilian tragedy for a period, but now it’s basically over.

Well, as it turns out, the truth is much, much more complicated, fascinating, tragic, and thought-provoking. The roots of the conflict stretch back at least 300 years, and putting it in the “religious conflict” box misses many of the core issues that perpetuated high feelings and then violence for so long. Stuart gave me a book he thought (correctly) might help, and which I then read cover to cover: it is called Voices from the Grave, and I talked about it a lot over here. It definitely helped me understand more about the two sides of the conflict, their respective histories, and the formative moments of the Troubles whose effects can still be seen in the Northern Irish psyche today.

Joel described this mural as “the Mona Lisa of the Shankill,” since the muzzle of the shooter’s gun points at you no matter where you are standing.

I found our long stroll through the Shankill Road deeply affecting. I confess I was upset to see the children playing beneath the murals whose pictures I’ve pasted in here, to know that they live in these very buildings and come and go every day under this kind of imagery. When I was repeating this story after the fact, one of my friends chided me gently for being so surprised, reminding me that the majority of the children in the world grow up under these kinds of representations of violence, and that it is only this very ring of iron and steel that privileged nations have laced through our colonial victims that allows us to live cushy lives of relative peace.

At the Falls Road memorial to fallen Republicans and Catholic civilians, a metal mesh backs the side of a Catholic house, so that any bombs or debris thrown over the Peace wall will be deflected from the house itself.

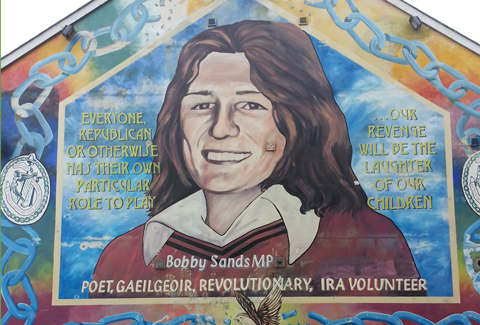

After the Shankill, we went to visit the Falls Road, the working-class Catholic neighborhood that would become the center of the IRA/Nationalist movement. We visited the memorial to fallen Republicans and stopped to observe the mural that adorns the side of the Sinn Fein headquarters building: hunger protest martyr Bobby Sands, who died at age 27 after 66 days of self-starvation in the notorious Long Kesh prison, called the H Blocks, which both Catholic and Loyalist political prisoners and paramilitarists made famous in the 1970s and 1980s. (Only by reading the book Stuart gave me did I discover that Bobby Sands was also a lyricist, and had composed in the jail where he would die a song my father used to play for me when I was a kid.)

The Bobby Sands commemorative mural painted on the side of Sinn Fein headquarters.

A Shankill mural commemorating those who served time at Long Kesh, the infamous prison that was home to the 1980/1981 hunger strikes.

Joel also took us to the Peace wall that separated the Shankill from the Falls. I was encouraged to leave my graffiti, like many a tourist before me (including Justin Bieber).

Guess what I wrote?

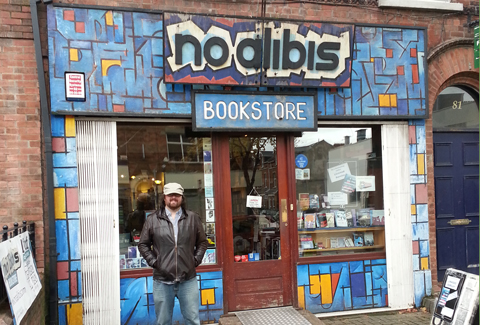

Just as we ended our political tour, the skies opened up, as the poets say, and Stuart found us refuge in exactly the kind of place I like to find refuge: No Alibis, a wonderful crime specialty store in downtown Belfast. I think we were in there for at least two hours. The owners, David and Claudia, are terrific, and I had a great time browsing. I’m afraid I came away from Ireland with a lot more luggage than I arrived with.

Stuart, in front on No Alibis Bookstore

The few hours I was able to spend in Belfast were exhilarating and eye-opening. It was a trip I came home from desperate to read as much as I could get my hands on about all the things I had seen. Since I first met him, Stuart has written three more books, each as wonderfully character driven, atmospheric, and politically complex as The Ghosts of Belfast. But I think before I visited Belfast I hadn’t wrapped my head around the true scope and nature of the Troubles–nor had I realized how real Gerry Fegan is. He might be a fictional creation, but he represents one facet of a generation-long conflict. I do look forward to revisiting Stuart’s books with fresh, better-educated eyes as soon as I can.

(Sorry, everybody, for the lousy photo quality; these were taken with my phone and I have never been famous for my photography. We editors are encouraged to cultivate other skills.)