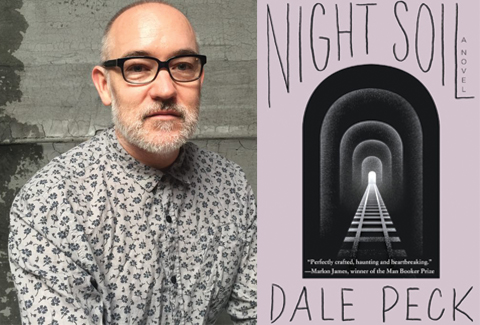

Dale Pecks’s Night Soil is now available in stores everywhere. Like the rest of his work, the prose is compelling and lush and it drives forward a “brilliant, beautiful, provocative novel about art, society and human consciousness itself.”

With that in mind, we combed through Peck’s other Soho Press novels for more instances of terrific writing (they were not hard to find). Here they are in no particular order.

Enjoy!

The Garden of Lost and Found:

The city cracked. That happens sometimes: eggs, ice, glass (also frescoes, facades, knuckles, and of course nuts, but I’m trying to be literal here). The city cracked, but didn’t break. Before, New York had simply been dying, but afterwards the focus changed, as the city insisted it wasn’t dead yet. The declarations were everywhere, the ribbons, flowers, candles, photographs, personal belongings (birth certificates, T-shirts, favorite poems; then more esoteric items: house keys, chunks of volcanic rock, a braided tassel of wheat), all sealed in plastic and taped to walls and lampposts and windows, as if the dead needed only a few reminders of who and what they’d been in order to find their way back. There were other things. The ash, of course. The flags and graffiti, pro-American, anti-Arab. The soldiers and camera crews. But all this proved transitory. In the days following the attack a series of thunderstorms washed a lot of the mementos away, and what the rain didn’t take was eroded by sun and wind over the course of the next several months. Sun and wind, street sweepers and souvenir seekers and terrorism tourists, not to mention a convoy of flatbed trucks that carted away the I-beams and body parts late at night, while people were sleeping and traffic was thin. Within a few months the city looked more or less as it always had, save for a few memorials here and there, the altars in front of firehouse, the notices of subway rerouting. And, of course, that one big hole, out of which the city’s soul threatened to pour like the white of an uncooked egg.

***

Martin and John:

On the night my mother died, a hard dry wind was blowing in off the ocean. You’d think that a west-moving wind would carry moisture, but it didn’t: it was dry and gritty as sandpaper, the kind of wind that blows in Kansas. It bit my cheeks as I hailed a cab, and inside the car, hot dusty air filled my throat. The air gave the city a grainy impression, and I found myself looking for a hidden camera recording me, the only child on the way to retrieve his mother’s last effects. If someone asked about her, I used to say that she was dead, she died a long time ago, I don’t even remember what she looked like. But my mother’s face hides just behind mine; I need only glimpse myself and I see her, and every memory I have of her life before she went to the hospice. I know nothing of her life since then. This was my doing, not hers: just before she left I asked her not to mail any letters she might write.

***

Night Soil:

Over the previous few years I’d developed the habit of turning my right ear toward people so I could hear them better. I didn’t realize I was doing it at the time, and most people, I’m sure, thought I was simply shielding them from the mottled left side of my face, which infuriated me, especially since I could feel them take advantage of my averted gaze to stare. My mother was as guilty of this as any stranger. Now, when I jerked my face back toward her, her mouth dropped open in a gasp and she looked away, only to gasp again, one wrinkled hand, prematurely aged by her work and her penitent baths, flying to her mouth and trying vainly to stuff the breath back into her body.

***

Greenville:

The boy stares at him as the doors of the yellow Bluebird close and the bus heads east down 38. His fists remain drawn for a moment, then all at once he throws his books on the grass, plops down and unlaces his boots, chucks them into the ditch. There is a splash as one of them lands in a puddle and at the noise the boy throws himself on his back and stares up into the pale green five-fingered leaves of the silver maples in the Flacks’ front yard. Star pasta, he thinks, but he can’t remember its proper name.

***

The Law of Enclosures:

On a map Long Island’s roads resemble a skein of yarn that’s been had at by a cat: they’re a tangle of bypasses, detours, alternate routes looping in and out and over and under each other so many times that it’s impossible to know quite where you are, and yet impossible to lose yourself either, owing to the finite nature of an island’s geography. In practice this meant that Beatrice could drive for hours without going anywhere, and this relieved her worry that something would happen to Henry and she wouldn’t be able to get him home. What would happen, she wasn’t sure, but in her imagination it took the shape of a fit, an epileptic seizure, convulsions and spasms and vomiting; and it was home she had to get him to, not a hospital, and why that was she also didn’t know.

***

Now It’s Time to Say Goodbye:

Abandonment is impossible. Memory persists, despite all the odds, despite all our efforts. Amnesia is like the color black: it effaces by inclusion. Excluding nothing, no one thing can come to prominence. And so I return to my abandoned beginning, my false start: If it’s after midnight it’s my birthday. If it’s after midnight then I have somehow managed to live for twenty-one years, and now I embark on my twenty-second. For the past five of those years Colin has orbited me like the moon orbits a planet, and what seems like years and years before Colin I orbited another man like a planet orbits a sun. But now I declare myself to be a comet, a celestial body with its own path, neither dependent upon nor depended on by anything else. This book is a telescope. Look through it; look for me: my bright and shining eye, my halo, my tail, stretching out behind me. You might view that tail years after I’ve passed by; I might have imploded, exploded, collided with something else and disintegrated, I might have run out of gas or, who knows, I might be blazing still, but in any case my tail lingers on, fading, but fading so gradually that you’ll never know if what you see is real, or merely a shadow burned into your eye.

***

Visions and Revisions:

So we were being killed in the summer of 1993. This, too, is a simplification, and probably melodramatic as well. Nevertheless most queers know we are being killed every summer, in ones and twos, in fives and tens and twenties. The summer of 1993, however, the killings were brutal enough and numerous enough, the details of the cases sensational enough, that for two weeks the story of gay death was considered “newsworthy,” which is another way of saying that it was “of general interest,” which meant, in short, that straight people could be assumed to want to read about gay death. At any rate it was more interesting than yet another closeted actor dying of AIDS.

***

Buy from IndieBound | Buy from Barnes & Noble | Buy from Amazon | Buy from Soho Press