The Critic

“It’s easy, after all, not to be a writer. Most people aren’t writers, and very little harm comes to them.” —Julian Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot

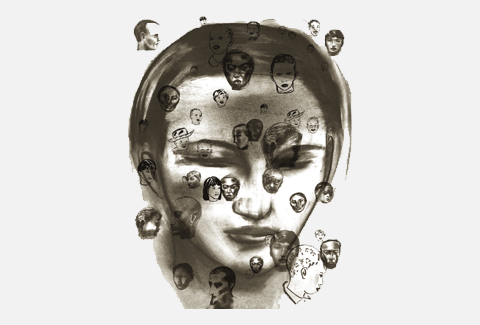

Everybody’s a critic. The problem for writers (for artists of any kind, really) is that everybody is a self-critic. We’ve all got that yammering, nattering inner voice that deprecates our talent, sneers at our work, snickers at our attempts to make it better, and generally tells us we’re a waste of the planet’s water and oxygen.

The critic’s one and only goal, when we’re writing, is to get us to quit. You quit, it wins. You finish, it loses. Then it slinks away into its dank cave, littered with the bones of our abandoned ideas, and waits for next time.

I personally believe that this little bugger is the most disagreeable of our inner children, the one whose head we held under water when we decided to grow up to become acceptable human beings, and it’s come back from the dead for revenge.

And we listen to it.

I listen to it. I listen to it even though I know it has my worst interests at heart, even though I know it has nothing constructive to suggest, even though I know it has the easiest job of any of the various versions of me that pop their heads up and chime in when I’m writing.

Think about it. There you are, with all your faculties fully engaged: Your imagination is at work, you’ve summoned up courage, you’re exercising discipline, you’re ransacking your heart to find something that matters, you’re using every available atom of your talent and skill to get that something onto the page. This is an enormously complex activity.

And what does the critic have to do? It has to stick its thumbs in its ears, wiggle its fingers, and go, nyaaa nyaaaa nyaaaa. This is about as complex as learning not to drool. The lizard-brain could handle it, with energy to spare for picking its teeth.

But we take the critic seriously. In fact, it can terrify us. It can make us quit writing.

It would dishonest of me to tell you I always know how to handle my inner critic. There’s no ritual that sends him muttering away in defeat. I haven’t got an uncomfortable stool in a corner I can make him sit on. There are days (especially in the middle of my book) when he gives me a real run for my money. There are days he actually makes me take my fingers off the keys, get up, and go do something—anything—else.

But I can’t allow him to keep me away for too long, because my book will die. Sooner or later, and it really has to be sooner, I have to slap him into shape.

Here are a few of the ways I deal with my inner critic. I hope fervently that you find some of them helpful.

I tell him to go f**k himself. Seriously. It’s not like he can hit me. I summon up all the scorn at my command, command him to buzz off, and write like hell. After all, that’s the point. If you don’t stop writing, he’s lost the battle.

I write something else. He often attacks by ridiculing the scene I’m writing or telling me that my characters are thinner than the page they’re printed on. Rather than wasting energy on arguing any of those points, I hang up that scene temporarily and go do something else—tidy up something I wrote a few days ago, start a scene that’s a little bit down the line, or find a new way to describe something. Or I use him to force myself to do some real good. By the time I’m halfway through a book, I know there are lots of places that, for want of a better word, are zits. Little pieces of writing that didn’t work the first or even the second time. Maybe it’s someplace I wrote “rhubarb” (see “The Dread Middle”). One way to tie my critic into knots is to use his or her interference as an excuse to go back and make one of these little snarls better. Then I do another one. (Look – I’m writing!) If he won’t go away, I just do this kind of tidying up for the rest of the session, and then go back to the original scene next time.

I take a shower. When I’m having a hard time writing, I’m the cleanest human being in whatever hemisphere I happen to be in. There’s something about the flow of warm water that just opens all the channels to the dreamworld in which my story already exists. It frees my mind to consider connections, consequences, alternatives. Dialog pours down with the water. By the time I’m clean, I usually have so much to get down that I wish there were some way I could actually write in the shower. (Anybody who invents something that would let me do that should advertise it in Writer’s Digest.) And once in a while, I actually visualize myself washing that critic off my back, which is where he usually seems to sit. Taking a walk also works, and for all I know, pumping iron or baking a cake would, too.

I give myself some credit. I remind myself that I actually have written good scenes before. I ask myself why I should even imagine that I can’t do it again. And I remind myself to be as kind to myself as I would to another writer. If someone reads her work to me, I’m not going to roll my eyes or make raspberry noises behind my hand, or say, “Hey, is there going to be a quiz?” I’m going to listen sympathetically, looking for the strongest bits, and then offer (if I’m asked) my thoughts on how to make the whole thing work a little better. I have to treat myself that nicely, too.

I talk to somebody. My critic is really only effective when it’s just him and me. Ninety percent of the time, if I take the scene he’s sneering at and the doubts he’s raised, and discuss them with someone else, the solution appears before I’m halfway through.

I give him a name he doesn’t like, and I use it. Sound childish? It is. But so is going, nyaaaa nyaaaa nyaaaa. My inner critic doesn’t like to be called “Herbie.” If I just say (often out loud), “Oh, Herbie’s arrived,” or “Shut up, Herbie,” or, “Hey, Herbie, your pants are falling down,” or any of a number of other really sophisticated things, Herbie will sometimes subside. On a really good day, I can make him burst into tears.

You’ll undoubtedly develop your own techniques for banishing your inner critic to the outhouse (although, of course, he or she will be back). But here’s what you don’t want to do. You don’t want to confuse your inner critic with the part of you that asks, “Would this be better?” Or, “Instead of doing this, what would happen if I did that?”

If the little voice in your ear is offering something even vaguely constructive, listen. If your characters do or say something unexpected, listen. That’s one way your book will grow, and you need to remain open to it.

But when your inner critic pipes up, you need to shut that little sonofabitch down. And the way to do that is to keep writing.

* * *

Ed. note: This is the twenty-fourth post in a series. Check out the Table of Contents to see what’s in store, and be sure to come back next week for a new installment.

Information about Timothy Hallinan’s next book in The Junior Bender series, HERBIE’S GAME, is here.