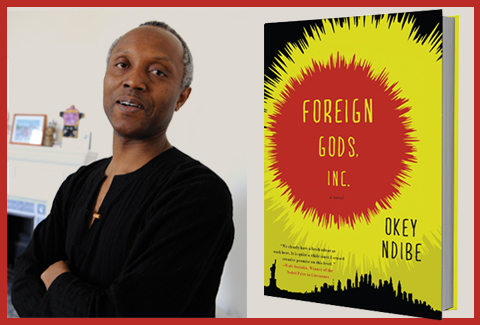

Okey Ndibe has written a novel that wrestles with bad faith and the post-colonial condition in equal measure.

Foreign Gods, Inc., of which Wole Soyinka, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature said, “We clearly have a fresh talent at work here …” releases this January from Soho Press.

Below is the second in a three-part interview with the author conducted via email (read part 1 here and part 2 here).

Paul Oliver: “A heist story like no other” is how Booklist described the core plot of Foreign Gods, Inc. This novel really does succeed in creating tension of the kind usually found in genre fiction. Weighty themes concerning race, identity, greed, and religion are apparent from the outset and clearly the reason you wrote the novel. But how much did you worry about writing a page-turner as well?

Okey Ndibe: Did I set out to write a page-turner? To keep the reader invested, captivated, viscerally moved by the turns and twists of the story – those goals shape my narrative choices. Inevitably, I hope, it all boils down to something like a page-turner. You can’t interest someone in polemics if they have little care about what happens next.

PO: On January 9, 2011, Nigerian security agents arrested you on your arrival at the international airport in Lagos. You were subsequently detained, and had your Nigerian and US passports confiscated. Did you see the arrest coming? How did you react to what followed?

ON: Did I see the arrest coming? Yes and no. In late 2009, I had received two anonymous calls warning me not to show up in Nigeria. The callers disclosed that the Nigerian government, then under Umaru Yar’Adua, had put my name on a list of “enemies of the state” and ordered my arrest if I showed up at any Nigerian port of entry. It was all so bizarre, so sordidly Orwellian. My weekly column for a Nigerian newspaper had apparently riled the Yar’Adua regime. However, Mr. Yar’Adua died in May 2010, and Goodluck Jonathan took over Nigeria’s presidency. On Mr. Jonathan’s first official visit to the US, two of his aides rang to invite me to meet with him in Washington, DC. I declined the invitation, but raised the issue of my status as “an enemy of the state.” The two officials assured me that Mr. Jonathan had ordered that the “enemy list” be erased. So, yes, I knew that I had been branded an enemy, but I was under the impression that the whole list had been tossed. So I was somewhat surprised when an immigration officer at Murtala Muhammed Airport told me he was going to hold on to my passport, and that I should grab my luggage and return to him because the Nigerian security agency at the airport wanted me. I used the occasion of picking up luggage to call friends and colleagues in the US. Within a few minutes, news of my detention was on the Internet. Wole Soyinka (winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize for literature) issued a statement condemning my arrest. From there, it became a whirlwind. The news was widely reported by newspapers around the world. Writers, writers’ groups, newspaper editorials, columnists, academics, and numerous Nigerian organizations voiced their outrage. Three days later, a top security official returned my passports, assured me that my name had been erased from any list of “enemies,” and blamed it all on the deceased Yar’Adua. Later, Nigeria’s top security official told the editor of the newspaper that carries my column to ask me to write a petition to him officially demanding the removal of my name from the list. I refused; since I had not, after all, asked anybody to put my name in the roster of enemies of the state, it was not my place to urge deletion. I have since been stopped and briefly detained five times, most recently in January 2012 when I was held overnight – for more than ten hours – at the same Lagos airport. My reaction is a cross between amazement and indignation. Some of Nigeria’s worst criminal elements, including governors and ministers who looted millions of dollars of public funds, go in and out of Nigeria with no impediment whatsoever. My only crime is that, week after week, I call out the corrupt in my column, and expose the scam that passes itself off as governance in Nigeria – and occasionally elsewhere. I can’t see much of a future for a country that makes a point of shielding, even glorifying, scoundrels, but hounding innocents.

PO: It seems to me that African literature is enjoying a bit of a renaissance at the moment. Writers like NoViolet Bulawayo, Teju Cole, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Mukoma Ngugi have all enjoyed success with their recent books. Not to mention the likes of Wole Soyinka and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o . . . Do you have any theories about why African literature is popular at the moment?

ON: I suspect that several factors built up, slowly, inexorably into this current renaissance in African writing. But I’d argue that the wide interest in works by African authors isn’t altogether a new phenomenon. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart has sold more than 10 million copies in English, and been translated into some 60 languages. We’re all indebted to him in a significant way, because his commanding presence in the canon of world literature went a long way in making what we call African literature visible, familiar, and desirable. Then we must not forget Wole Soyinka’s Nobel in 1986, with the traction and gravitas that come with the prize. Soyinka’s Ake: The Years of Childhood was a New York Times bestseller. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, whose roundedness and eminence as a literary artist make him one of my favorite writers of all time, has apparently – deservedly – emerged as a serious candidate for the Nobel. Then there’s the Caine Prize for African writing, which awards some $15,000 to a short story. The prize has its annual buzz index. It’s created a certain ferment. So there’s all of that. But there’s also the factor of serendipity, the fact that a few US and British publishers gambled on works by younger African writers – and discovered that there was a huge, excited and attentive audience out there. Ben Okri’s Booker for The Famished Road provided a huge tonic for African writers. Chimamanda Adichie’s radiance and stupendous talent command attention. Teju Cole’s Open City dazzles with the sheer luminousness of its style, its effortless intelligence. There are many others – Zakes Mda, Nuruddin Farah, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Chika Unigwe, Emmanuel Dongala, and Helon Habila among them – whose extraordinary writings continue to stamp our literature on the world’s consciousness. One can’t minimize, much less discount, the Internet’s role: how it has unbound once-repressed voices, how it’s catalyzing the bursting forth of some magnificent writing, a variety of styles and accents of storytelling. For all the wonderful things happening around African writing, I’m often deeply sad that the “metropolitan” publishers in New York, London, Brussels, and Paris are mostly responsible for husbanding much of African writing, introducing it to the world – and, in many cases, to Africa. I’d like to see a robust publishing industry take root throughout Africa to match the continent’s energetic creative talent.

PO: The late Chinua Achebe played a significant role in your life and career. From giving you your first big interview for the Nigerian Sun to co-founding Africa Commentary with you, Achebe was a huge influence for you. It almost didn’t happen, though, thanks to a tape recorder malfunction, and you very easily could have got off to a bad start with the great writer. How did that go down?

ON: My first interview with Achebe, in 1983, was also my very first significant assignment as a rookie correspondent for the now long defunct African Concord, a weekly magazine. That first interview set a mood for my relationship with the author – he saved my career.

I met Achebe quite by accident. I was visiting a girl from Ogidi, Achebe’s hometown. I raved on and on about Achebe and his best known work, Things Fall Apart. The girl listened for a while, a bemused smile creasing her cheeks. Then she said: “Achebe is my uncle. His house is a short walk away. He happens to be home this weekend. Do you want to visit him?”

Did I ever!

The Achebe I met in his country home personified grace. I still remember that he served us cookies and chilled Coke. He regarded me with penetrating eyes as I gushed about his novels, his short stories, his essays, even reciting favorite lines. I told him I had just got a job with the Concord magazine and would be honored to interview him. To my surprise, he gave me his telephone number at Nsukka, the university town where he lived and ran the Institute of African Studies.

A week later I flew to Lagos, reported for work, and told the magazine’s editor that I had Achebe’s telephone number—and a standing commitment that he would give me an interview. Elated, the editor dispatched me on the assignment. It was my first real task as a correspondent.

Achebe and I retreated to his book-lined office at the institute, its air flavored with the scent of books stretching and heaving. Five minutes into the interview I paused and rewound the tape. The recording sounded fine and our interview continued for another two hours. Afterwards Achebe told me it was one of the most exhaustive interviews he’d ever done. I took leave of him and, heady with excitement, took a cab to the local bus stop where I paid the fare for a bus headed for Enugu, the state capital, where I had booked a hotel.

That evening several of my friends gathered in my hotel room. They asked questions about Achebe, and then said they wanted to hear his voice. I fetched the tape recorder, happy to oblige them. Then I pressed the play button. My friends and I waited – not a word! I put in two other tapes, the same futility. How was I going to explain this mishap to my editor who had scheduled the interview as a forthcoming cover?

I phoned Achebe’s home in panic. I begged that he let me return the next day for a short retake. “Thirty minutes—even twenty —would do,” I pleaded. I half-expected him to scold me for lack of professional diligence and then hang up, leaving me to my distress. Instead he calmly explained that he had commitments the next day. If I could return the day after, he’d be delighted to grant me another interview. And he gave me permission to make the next session as elaborate as the first.

Two days later we were back in his office for my second chance. This time I paused every few minutes to check on the equipment. I stretched the interview to an hour and a half before guilt—mixed with gratitude—compelled me to stop. It was not as exhaustive as the first outing, nor did it have the spontaneity of our first interview. But it gave me—and the readers of the magazine—a prized harvest. My friends got a chance to savor Achebe’s voice, with its mix of faint lisps and accentuated locutions.