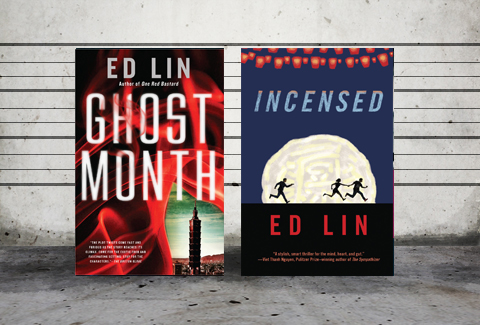

You have two choices if you want to visit the beautiful tropical island of Taiwan. Either buy a plane ticket and suffer through a seventeen hour flight, or pick up copies of Ghost Month and Incensed by Soho Crime author Ed Lin. Either way, you will find yourself on a lush, green, humid island surrounded by fascinating people of multiple ethnic groups and numerous dialects and eating exotic food laced with explosive flavors and tripping over secrets from the past that erupt like land mines during every few steps of your journey.

I studied in Taiwan many years ago when it was still ruled by the Kuomintang and the family of Chiang Kai-shek. Many of my memories had started to fade but when I read Ed Lin I’m transported back in time and I’m feeling the heat and hearing the firecrackers and gazing into the snarling red lips of porcelain dragons in temple courtyards infused with the odor of burning jasmine.

The character of Jing-nan (aka Johnny) and his food stand in the Shilin Night Market and the corrupt cops and the all-pervasive triads and the ancient superstitions that seem to invade every nook and cranny of Taiwanese life, give Lin’s writing a realism that is physically palpable. When I read his stories, I’m ready to hop on a motorbike and speed through the streets of Taipei and enter any dark den of iniquity and imbibe any long-fermenting reptilian liquor that might be thrust in front of me. In other words, I’m young again.

I can’t promise you that by reading Ed Lin, you’ll literally regress in age, but I can promise that immersing yourself in Jing-nan’s life in Taipei will clear your sinuses and wake you up like a dose of smelling salts to the nose and a hard slap to the cheeks.

Light a joss stick. Smell the incense. And welcome to the multi-sensual literary world of Ed Lin.

Martin Limón: Where did you get the idea for the character Jing-nan (aka Johnny)?

Ed Lin: My family had a business, a hotel, that I had to work at while growing up. I was heavily encouraged to do well in school but the greatest inducement to excel was visions of being stuck at that counter for the rest of my life. I wondered what it would be like for someone who ended up getting stuck that situation, if one could make peace with it, or even kick it up a notch. Johnny is certainly helped with the explosion of foodie culture. I personalized the character by giving him the same Chinese name as mine (景 南)!

ML: I loved the character of the brilliant but disturbed teenage girl, Mei-ling, in your forthcoming novel, Incensed. Can you talk about writing female characters?

EL: I have a bunch of younger cousins and many memories to draw upon from when they were girls and growing up under domineering parents. Taiwan has a fairly modern society but it still has a bunch of old chauvinist ideas it would be well rid of. For Mei-ling, which is a common name, I imagined a rather uncommon and uncompromising girl who would fight ’em all, possibly to her detriment. In general, I try to approach developing female characters the same as I do with men—I try to keep it atypical and specific. I want to catch my readers unaware in terms of plot and character.

ML: The red envelope (hongbao) nightclubs in the Ximending district of Taipei are so evocative. Old soldiers gathering to hear over-the-hill performers sing out-of-date songs. Where did you come up with the idea for places like that? Do they actually exist?

EL: They really did exist and the ones that are left are hanging by their fingernails. I have a picture from 1975 of an old soldier in the street on his hands and knees, bawling his eyes out at the news of the death of Chiang Kai-shek and crying out, “Take us back to the mainland!” That soldier had fled to Taiwan 25 years before, when he was still sort of young, and believed he’d charge back and recover the mainland. With the death of Chiang, that gung-ho illusion was finally and fully dispelled. I thought that when that soldier was finally able to pick himself up, he’d go to a hongbao nightclub and pay a woman to sit with him at his table as he cried and cried some more.

ML: When I was in Taipei years ago, I didn’t notice the use of betel nut. Everyone seemed to have clean teeth. Has its use increased over the years? How about the stands with the scantily-clad hostesses. Is that also a recent innovation?

EL: I think betel-nut chewing is something that the Japanese discouraged when Taiwan was a colony and later Chiang and the KMT tried to stamp it out, but it is a native Taiwanese habit that has nonetheless flourished. Doing so now by the younger generation is an assertion of their “Taiwaneseness.” The “sexy” angle has been around for at least a decade and it seems it’s here to stay, just as strippers at funerals have attained permanence. You know how boring the highways would be without betel-nut beauties?

ML: From the beginning of Ghost Month, Jing-nan is trapped paying off a gambling debt he inherited from his grandfather that his family owes to a Chinese triad. If he tried to return to the States without repayment, Jing-nan informs us, there would be a “price on his head.” Do the triads really have this powerful a hold over the Chinese people and are their rules enforced internationally?

EL: I’ve interviewed a number of people in organized crime in Taiwan. Like almost all people in Taiwan, they are incredibly polite nearly to a fault and extremely forthcoming. One guy I spoke with who is in one of the larger organizations said they had ties all over the world, in particular with groups in the U.S. I would say that people in criminal organizations have a strong sense of honor, which is why they hold in high regard the protagonists in the Chinese classic novel Outlaws of the Marsh where the so-called “outlaws” are like Robin Hood who are fighting a corrupt government. They are a proud people and with them there is no such thing as a statute of limitations on unpaid debts (no matter how small) or an insult. Just last year a Taiwanese businessman and his wife in the Philippines killed their three children and then committed suicide because they couldn’t repay their debts to loan sharks. I wouldn’t say that criminal groups hold a world-wide sway over ethnic Chinese/Taiwanese, but if you owe them money and can’t pay it right away, work out a payment plan with your representative—don’t try to skip town.

ML: I found that Taiwanese are reluctant to speak frankly about what they see as folk superstitions; especially to a foreigner. In addition, most of the books I’ve read on the subject have very little specific information on the local deities and how they are viewed. Your books are the exception. In Ghost Month and Incensed you’re revealing what amounts to Chinese cultural “Top Secret” information. I’ve learned more from them than I have from any number of non-fiction intellectual tomes. For example, you inform us that when giving gifts to Tu Di Gong “include a generous serving of rice cakes to stick to the roof of the mouth so he can’t say anything about your bad deeds.” Do you agree that you’ve opened up about things—specifically superstition—that other Taiwanese have been reluctant to talk about?

EL: Taiwanese are friendly people but by nature are tight-lipped about their goddesses and gods. I think there are a few reasons for this. For one thing, people have personal relationships with their deities and in their prayers they speak/think frankly and openly with them in ways they can’t with their own family. To speak with anyone else about them (much less with a foreigner [gasp!]) would violate the sacredness of that relationship and could even possibly result in divine retribution. Also, during the Japanese colony years, the authorities tried to stamp out Taoist and folk deities because they were seen as too “Chinese,” so Taiwanese hid their idols among the Buddhist shrines or in the walls of their houses. (Buddhism was acceptable to the Japanese.) That sense of concealing and protecting the deities remains with the Taiwanese. I think the main reason why there aren’t guidebooks about the various goddesses and gods is that each means something different to different people. For example, Mazu, the Taoist goddess and most popular Taiwanese deity, originally represented a protector of fisherman but her powers have expanded to bestowing rain to farmers, helping women conceive and other heavenly capabilities. I’ve definitely opened up about what Taiwanese won’t talk about, but I think that if most of them read my interpretations, they would shake their heads and say, “That American writer’s got it all wrong!

ML: There seems to be some exquisite research going on in Incensed. For example, an idol holds a ruyi, a short curved scepter with a knob at one end that resembles a back-scratcher with a tassel attached to the bottom. (Can I buy one at Wal-mart?) In the other hand, the idol holds a yuanbao. It is a metal ingot shaped like an egg with a brim. You go on to explain that tough guys in Chinese historical novels could break off pieces of the brim with their bare fingers to pay for trifling amounts of food or drink. How in the world did you know all this? Is it from research or is it from having grown up within Chinese culture? Were you educated in a Chinese school or an American school or both simultaneously? This seems to me to be another marvelous example of readers being allowed to go where no reader has gone before.

EL: Oh, shucks, I’ve just grown up with these images, being in a Taiwanese/Chinese household. Doesn’t every house have a Guan Gong statue bearing a fearsome moonblade? I have been slowly reading, over the years, volumes of Chinese folktales along with the standard classics. With something as ancient as the ruyi, the origin is obscure but the contemporary meaning of “fortune” was good enough for the builders of the Taipei 101 skyscraper to put giant ruyi representations on the sides. We had a gold yuanbao, on the mantel (doesn’t everyone?) and I while I read about the heroes in Outlaws of the Marsh, I thought, they must totally break off pieces of it for the inns where they got wasted! I did go to Chinese school for a number of years, but I was a lousy student and landed on the “dumb track,” which was essentially babysitting. Chinese school in America in the 1970s was essentially KMT propaganda, anyway, and was more geared toward opposing Communism and worshipping the KMT and Chiang rather than truly teaching about Chinese culture.

8. You say, “Confucius was right to hate children.” I hadn’t realized that. Is this a common perception in Chinese culture?

That’s me being snarky. I think those revisionists, the neo-Confucianists, have perverted the original message into being right-wing, conservative and authoritarian. Pinning societal failure on the lack of discipline in children rather than a failed system. I think a lot of Asian Americans ascribe to a fake Confucianist ideal where kids are supposed to study and get all A’s or face punishment. Yet Confucius himself pushed for art and music education and said that a man who didn’t understand poetry wasn’t worth listening to.

9. You mention that tourists consider Taiwan to be “a great vacation place that was seemingly crime-free. What they don’t know won’t hurt them.” When I lived in Taiwan, I considered Taiwan to be virtually crime free. At least free of violent crime. I was burglarized a few times but the thief seemed quite polite; even though as a poor student I owned little of value. This is another example of you portraying Taiwan as being the mirror image of what the foreigner imagines. Do you believe you’re “spilling the beans” here to the wider world?

I stand by with what I’ve read in a Taipei guide: If you don’t patronize prostitutes or buy drugs you likely won’t come face-to-face with anyone in the underworld. I feel that Taiwan is like Japan in that the criminal organizations have legitimate enterprises and operate as legally as, say, mortgage lenders do in the U.S. Am I spilling the beans? I dunno. If visitors asked a criminal for directions, he would probably walk them to the corner and make sure they knew where to go. The visitors would think, “What a nice young man with lovely tattoos!”

10. On page 87 of Incensed you refer to Mei-ling: “Like most Taiwanese, she sounded nice and innocent when she spoke English.” Talk about bursting my bubble! When I was there, I thought most Taiwanese were innocent. Where do you get these insights? Is it your mission to break down the illusions that divide the people of Taiwan from the West?

Actually, this goes back to when I was working at a children’s-services nonprofit in Manhattan’s Chinatown. I remember this at-risk kid, who talked tough and pushed around smaller boys, once had to ask me for something. His whole personality changed when he spoke English and he even gave me a meek, “Thank you.” I think because many Taiwanese learn English in school, they revert to their best school behavior when they speak the language. The main illusion that the people of the West have of Taiwan is that it’s a province of China! I hope I’m breaking that one down!

11. I’m always looking for little details to provide verisimilitude to my writing. You appear to be a master at it. In a Japanese-style home, the “two pillows were filled with buckwheat chaff.” I’m impressed. How did you know that?

I have a pretty awesome memory that is both a blessing and a curse, and one thing that I remember from a family trip to Japan is that there were two types of pillows in the hotel–one with feathers for Westerners and one with buckwheat hulls for the Japanese. I didn’t know it was buckwheat hulls, of course, but as I was changing money in the hotel lobby, I asked the clerk what was in the pillows. He told me and mentioned that it was a traditional Japanese pillow filling. Years later, I saw an American commercial for buckwheat-filled pillows. They didn’t catch on as well as the “Ginsu” knife, however!

12. On page 286 of Incensed you write: “yelling as if testing the lobby for echoes . . . ” How do you come up with phrases as effective as this? Do you spend a lot of time searching for them or do they just come to you?

It’s all work for me, literally. I edit business news at my day job and a big part of it is coming up with catchy headlines. I’m a natural punster and I’ve learned to channel that to come up with expressions that convey a deeper meaning in addition to the literal words. In the unending editing process, sometimes I’ll rework a phrase again and again until it shines or has to be taken out (and shot).

13. On page 308 of Incensed you write: “The lone desk clerk was confronted with a group of Chinese who clung to the counter as if climbing out of the sea.” Another effective phrase. What struck me about this one was that many years ago I had to go to a bank in downtown Taipei in an effort to cash a Stateside bank check. There were no lines, only a mob of people confronting a tall female teller and clinging to her counter “as if climbing out of the sea.” I stood in back of the mob for a few minutes, making no progress forward, wondering what the heck I was going to do. Apparently she decided to reward my patience. Regally, she reached out her arm to me and accepted my check and motioned for me to step forward. The rest of the people made way and without a word of complaint I was allowed to conduct my transaction. It was as if she was a goddess and no one dared question her decision. I believe most Americans have never encountered such a scene and can hardly imagine it. Yet you manage to make these enormous cultural differences vivid, in just a few short words. Do you spend a lot of time wrestling with how to show your English-speaking readership what day-to-day life is truly like in Taiwan? It’s not like writing about Chicago or New York where certain cultural assumptions can be made and the reader can fill in the blanks. On the other hand, do you worry about spending too much time explaining cultural differences and thereby taking the risk of having the story bog down? The fact of the matter is that you don’t bog the story down and yet deftly explain these differences. What I’m wondering is, how hard do you work at getting it right? Or does all this come naturally to you? If it comes naturally, I’m jealous.

I’m sorry you actually had to witness that, Martin! How embarrassing for my people! Well, shoot, especially in a bank context, unfortunately many Taiwanese and the Chinese mainlander population have faced banks going under without the FDIC insurance on the accounts that U.S. banks offer, hence the “I must get on that boat!” desperation. From what I’ve seen at the Taiwan museums where Chinese tourists congregate, I’ve been shocked and awed by their bad behavior. I just imagined that it would be even worse in the situation of grabbing the best hotel rooms. I do worry about bogging down my stories with cultural baggage. In fact, my many detractors say that this is in fact the case! In all honestly, however, I would say that it is necessary to have it all. If the story seems like it’s dragging, that would actually be a good opportunity to catch my readers unaware and put a hammer to the back of their heads, so to speak. I agonize over getting everything as “right” as I can and apart from my efforts, I have to thank the many people I’ve talked to for helping me to the point of exhaustion!

14. What’s one thing I, and your readers, don’t know about you that would surprise us?

I’m allergic to nearly all seafood, so I can only eat about 30% of what Taiwan has to offer. I know, I know, this aspect of my life proves what a fake Asian I am! I’ve asked my wife to sample many dishes (such as Taiwan’s famed oyster omelet) and tell me what they taste like so I can get that part “right” in the books.

#SohoCrime25

Ed Lin is a journalist by training and an all-around stand-up kinda guy. He’s the author of several books: Waylaid, his literary debut, and his Robert Chow crime series, set in 1970s Manhattan Chinatown: This Is a Bust, Snakes Can’t Run, and One Red Bastard. Lin, who is of Taiwanese and Chinese descent, is the first author to win three Asian American Literary Awards. Lin lives in New York with his wife, actress Cindy Cheung.

Martin Limón retired from military service after twenty years in the US Army, including ten years in Korea. He is the author of eleven books in the Sueño and Bascom series, including Jade Lady Burning, Slicky Boys, The Iron Sickle, The Ville Rat, and the short story collection Nightmare Range. He lives near Seattle.