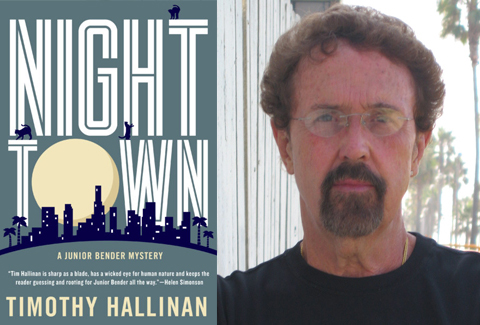

We are not the only ones excited for the release of Nighttown, the sixth installment in Timothy Hallinan’s award-winning Junior Bender series.

“Hallinan’s top-notch prose and plotting are reminiscent of Lawrence Block and Elmore Leonard.”

–Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

And from Booklist:

“Nobody does comic mystery with an edge better than Hallinan.”

Now, to stoke the flames of anticipation even more, here’s an audio recording of the author reading from the book’s first chapter (text below).

1

WEEEoooooo

By way of a prelude, a few words about the dark.

In the entire, staggering length of the Bible—Old and New Testaments combined, a total of 783,137 words—darkness is mentioned only about one hundred times, and it gets slagged almost every time. It’s identified with ignorance, hell, evil, exile, the absence of God, and other conditions to which few of us aspire. The only positive mention of darkness in the whole Book is when the Lord speaks to Moses after dimming the day to protect the Israelites from the sight of Him, and that good darkness, the one and only good darkness, is called by a completely different word, araphel, which will never be used again. Just that once. For God’s personal and merciful darkness.

It gets its own damn word to distinguish it from, you know, ordinary every-night darkness, which is Not Good.

According to the King James Bible, translated from a bunch of older languages by forty-seven of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, the Lord gets right down to business with the very first line he speaks: Let there be light, He says. And then . . .

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.

Night is just what’s left over after the big chop: over here, light, which is good; and over there, dark, which is definitely not good and which will be thrown at us, regular as clockwork, every sunset through eternity to lay claim to half of our lives, whether we like it or not. And we’re not supposed to like it.

As you can probably tell, I have a problem with this outlook.

I make my living, ninety percent of the time, in the dark. Burglars tend to prefer the dark because, while some of us are pretty dumb, there aren’t many of us stupid enough to begin a job by turning on the lights. One iron-clad rule of burglary is to avoid unexpected interactions with others, and darkness helps to prevent them. That was taught to me at the age of seventeen by my mentor, the late, great Herbie Mott, and he had the game down cold. Thanks to Herbie’s guidance, I’ve been at this game very successfully for more than twenty years and I don’t even have an arrest record, much less a conviction. I’m good at this, and I resent the way my old ally darkness is slandered.

It’s not that light is useless. I’m as fond of a sunny day as anyone who isn’t prone to melanoma, but I can’t help thinking that giving the sun the night off is one of creation’s better ideas. It rests the eyes, it allows plants a chance to take a break from making sugar. It clears the landscape for a lot of very interesting animal life. Most love is made at night, at least by people older than, say, seventeen. Many of the world’s most fragrant flowers bloom at night. In place of the monochrome blue of the daytime sky, night offers us the moon’s waxing and waning face, set off against the infinite jewelry of the stars.

If it seems to you that I’ve given this a lot of thought, you’re right. Nighttime, in a manner of speaking, is my zip code. It’s an undiscriminating neighborhood, one I share with disk jockeys, cops, ambulance drivers, insomniacs, air traffic controllers, French bakers, peeping toms, recovering drunks, speed freaks, the terrified, the bereaved, the guilt ridden, and those with the medical condition photophobia. Sure, it’s a mixed batch, but night also evens the odds for the blind and extends a hand of mercy to the odd-looking, the ones who draw stares in the glare of noon. It softens the edges of even our ugliest cities.

But there actually can be too much of a good thing.

I had never really subscribed to that idea, but as I stood in the entry hall of Horton House, holding my breath and listening—which is always the first thing I do when I enter a house—I was revising my opinion. Horton House was too dark. For the first time in my perhaps four hundred burglaries, it seemed like a good idea to just blow it off and go back out into the comparative glare of a moonless night.

And it wasn’t just the dark, which was so close to absolute that I might as well call it that. The house was noisy, in the way only an all-wooden house that’s more than a century old can be. Horton House had been built by a briefly prominent family in 1908, and every join, plank, beam, and nail was feeling its age and complaining about it. It was almost as loud as a sailboat, which (the claims of their owners notwithstanding) never stops creaking and moaning and sloshing. Horton House made so much noise that I was having trouble listening around and through all of it for the sound of something human: movement, breathing, snores, whatever. The place was supposed to be empty; in fact, a sign outside confirmed that the house was due for demolition in three days. Still, I waited and listened, as I always do, in recognition of the perpetual gulf between what I think I know and what’s actually happening.

The most off-putting of the house’s trinity of disquieting characteristics—the one I found even more disagreeable than the darkness and the noise—was its smell. One component was a sharp-edged stink that could only be really, really old paper, and I was willing to bet that my little penlight, when I felt secure enough that I was alone to turn it on, would show me the original wallpaper, more than a century old, clinging for dear life to the walls. And running just beneath the sharp wallpaper smell, like a large but muted string section supporting a snare drum, was a pervasive, over-sweet scent with an almost physical heaviness that I first guessed as long-dead flowers, maybe tuberose or narcissus or some kind of lily. It took me a full minute to realize what it really was.

Baby powder.

If what I’d learned about the house was true, there hadn’t been a newborn baby here since 1921, and the thought of the smells that baby powder might have been intended to disguise in these latter days was more than a little unsettling. The “baby”—Miss Daisy, the last of the Hortons—had died upstairs, almost exactly a month earlier, at the age of ninety-six after spending almost fifty years confined to a bed on the second floor.

Put it all together, and what it came down to was that Horton House had a certain WEEEooooWEEEoooo factor. The place absolutely hummed with malice. Miss Daisy, who had spent eighty years or so alone here, except for a skeleton staff of servants and a long and apparently unsatisfying succession of daytime caregivers, was semi-famous for hating everything. In her thirties, before the fall on the stairs that had almost severed her spinal cord, she’d been nicknamed “the Witch of Windsor Street” for her skill at terrifying children who dared to play on the sidewalk in front of Horton House. Her animus remained evident even after she gave up hoping for a cure and took to her bed: her response to the changes in her neighborhood, as the old houses went down and stucco went up to welcome an influx of new occupants whose native languages were more likely to be Spanish and Korean than English, was to put the evolving world literally out of sight and out of mind. First, she had her gardeners install the thick ficus hedge that surrounded the property and over-fertilize it until it was higher than the streetlights and the windows of the houses on either side. Second, when the home on her left was demolished to make way for a three-story apartment house with vaguely French Provincial pretensions, she covered the inside of every window in her own house with two layers of the heavy brown paper used for supermarket shopping bags. Dark as it was at night, in the daytime, the light in here in mid-afternoon must have been the rich color of caramel. I knew much of this because Miss Daisy had long been the Cruella de Vil of fading Los Angeles gentility, and as such, she’d gotten her share of newspaper space and, much later, TV time, although she was never seen on-screen.

Apparently, one of the more enduring marks she’d left on Horton House was the odor of that damn baby powder, a kind of cloying sweetness that bordered on decay. I hated it all the way to the back of my neck, which is a part of my body I’ve learned to pay attention to. Everybody gets the prickles in different places, I guess, but I get them on the back of the neck, and my neck had essentially been calling my name from the moment I opened the gate in the center of that towering hedge.

Which I had done with a key, by the way. The key alone should have told me from the beginning that something was off about the whole enterprise. I hadn’t even turned my penlight on, and I was already having second thoughts.

Still, I’d just hidden more than $25,000 in hundreds in my chimney at home and there was another $25,000 waiting for me when this errand was complete. I focused on that. Large sums of money create a powerful reality-distortion field, and in my experience it had rarely been harder to overcome. I was facing a problem that only money would solve, and the problem involved not only me but a person I loved.

So. All the creaks, shudders, and groans were just old wood, nothing that couldn’t be explained by the contraction of an arthritic old house. The smells, awful as they were, were just smells. Now that I’d forced myself not to go all fizzy because of the baby powder, I also smelled tobacco—not fresh, but the indelible nicotine funk given off by walls, rugs, and furniture that have been marinated in cigarette smoke for years. The place was dark and noisy and it reeked, but I seemed to be alone.

I flicked on the little penlight and played it around, startled for a second by a bulky shape right beside me, an authentic elephant’s-foot umbrella holder, probably from the 1920s: dark, wrinkled, gray skin that was thicker than any leather I’d ever seen, all hollowed out, with four huge toenails in a deeply unwholesome yellow, the whole thing almost hip-high on me. I stepped away from its potent creepiness, did a quick sweep for four-foot spiders and other unwelcome surprises, and embarked on my usual internal preview of the house I was about to explore.

Quite a bit had been written about Horton House since it was built, and as far as I had been able to see from the outside, it still had the original 1908 floor plan I’d read about. The entrance hall, stretching about thirty feet from the front door to the grand stairway, had broad arched openings on either side, the one on the right leading to the enormous living room and the study behind it, and the one on the left affording access to the dining room and the kitchen. This confirmation that I was right about something was a relief, because even though I needed the money so badly, I’d been unnerved by how much of it I’d been handed to pay this visit. In my line of work, too much almost always turns out to be not enough.

I tabled the thought and went back to my mental map. Assuming the second floor was as intact as the ground floor seemed to be, I basically knew my way around. The blind spot, if I had one, would be the servants’ quarters, which hadn’t made the cut for the society pages. Still, I expected to find at least one small bedroom, probably beyond the kitchen. Almost certainly there would be nothing important back there, but it’s always a good idea to get a quick look at the spaces you’re not sure about before exploring the ones you are.

The curved, darkly carpeted stairway at the hall’s end was wide enough to allow an entire barbershop quartet to sing their way down it, side by side. It led, I knew, to three upstairs bedrooms, two baths, the nursery, and the sitting room, where, I supposed, people once sat. In front of me at the end of the hall, in a recess just to the right of the stairway, was a small nook with a door in it. My guess was that it opened onto stairs leading down to the basement.

I was not going down to the basement.

Not believing in the supernatural doesn’t necessarily protect you from the heebie-jeebies. Reason lives in one room, and yes, I’ll concede that it’s a nicely lighted room, while unreasoning, primal, bogeyman fear lives in another. The door between the rooms is usually locked, which meant that my comforting, no-woo-woo belief system was not currently accessible. I stood absolutely still, four feet from the scooped-out elephant’s foot, with my back pressed against the front door, beaming that pathetic little finger of light around and asking myself why the hell I was there, even though I knew it was plain old money.

Look around. Looking around would divert me.

The penlight put out a yellowish beam that intensified the yellow of the ancient wallpaper on either side of the hall. As anyone who owns an old print knows, blue is the first color that light leaches away, and paper yellows naturally as it ages, so eventually you end up with a narrow chromatic scale that’s heavy on yellows, not so much a color wheel as a color semicircle. Wallpaper is no exception, and what had once been peacock plumes now looked like fancy fans and feather dusters made of straw. The hallway’s white ceiling was arched, like the doorways and the openings to the other rooms. The effect was beautiful in a slightly churchy manner. Builders used to care about the houses they built.

Dangling above me was a delicately angular wrought-iron chandelier. To my surprise, it was just perceptibly moving, although I could only see the motion in the magnified shadow thrown on the wall by my little light. Somehow, despite the nailed-shut windows and their brown-paper coverings, a draft had tiptoed in. I closed my eyes and tried to sense the moving air on my face. If I felt anything, it came from in front of me and, possibly, to the left.

Since the thought of an open door on the ground floor wasn’t reassuring, I decided to locate the source of the draft before I went upstairs. So I took a couple of steps and stopped, fighting the impulse to put my fingers in my ears. The floor beneath me yielded up an extraordinarily varied assortment of creaks and pops. I edged, just sliding my feet, to the left; floors creak less where their beams are joined at the wall. It was a little quieter, but by the time I’d reached the archway to the dining room I’d figured out that a movie company could have recorded an entire film’s worth of ominous groans, squawks, creaks, and pops in Horton House without even going upstairs.

Just before I made the left into the dining room, heading toward the kitchen area, I realized why the carpet on the stairway had caught my eye. The hallway floor, by contrast, was bare, but not, I thought, to show off the quality of the flooring. To confirm my hunch, I turned around and played the little flashlight’s beam over the juncture of walls and floor on either side of the long entrance hall. No question: the ten to twelve inches of wood closest to the wall had been bleached by decades of indirect sunlight, scarred and scratched by generations of feet, while the strip down the center, although dusty, was as lustrous as the soundboard on a fine guitar. It wasn’t hard to visualize the missing carpet: a fine old custom-made runner, thirty feet in length and a good five feet wide. Literally an antique, the label US Customs reserves for artifacts manufactured a century or more ago. If it hadn’t been ripped up because it was worn through or was in tatters, it had been worth a small fortune.

I turned into the dining room and angled my way relatively quietly along the walls, the windows not admitting a candle’s worth of light through their thick brown paper masks. The parts of the room I could see seemed oddly empty—I’d been told the house was still furnished—but I wanted to locate the source of the draft before I checked anything else. The temperature had dropped a little as I neared the kitchen, so I figured I was going in the right direction.

The dining room was so dark that I was completely unprepared for the chest-high flare of reflected light as I turned through the doorway into the kitchen. The glass in the windows above the sink and counter had been uncovered, undoubtedly the work of a cook, who needed more light to do his or her stuff and who knew that the mistress of the house was upstairs being sprinkled with that awful baby powder and wouldn’t be dropping in anytime soon. I snapped off the penlight and tried to blink away the black negative the reflection had printed on my retina. I couldn’t see much of anything but I could feel the draft more directly now, and it came from my right. When I could focus, I saw that the window directly above the end of the counter was open by about four inches.

Leaving the light off, I went to the open window and got the best look at it I could under the circumstances. Neither on the sill nor on the counter beneath it did I see any dirt or grass or other bits of the outside world someone might have brought in on his or her shoes. When I slipped my hand beneath the window, my gloved fingertips hit a screen, which appeared to be tightly in place. In the interest of thoroughness, always prudent when committing a felony, I passed my palm over the counter, which was greasy but not sandy or littered with shoe crap, and then I got down on my hands and knees and aimed my penlight at the floor. There were no footprints. I stood up and turned off both the light and my mind for a moment, simply not thinking about it. It’s a mental version of looking to the side of something you want to see when it’s dark.

With my light off, the world on the other side of the windowpanes had the wavy, somewhat watery appearance that’s the hallmark of old cylinder glass from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a process developed to create a sheet of glass big enough for larger windows. It was blown in the form of a long tube that was slit down one side and opened while still pliable and then put into an extremely hot furnace where it melted and flattened into a smooth but slightly rippled sheet. This was obviously the glass that came with the house, not a later replacement. When I got closer, though, I saw that I had been right in thinking that it had once been covered: The edges of the panes were a remarkably ugly brown where years’ worth of dust particles and cooking oil had adhered to the sticky imprint of the tape that once held the heavy paper in place.

Okay, I decided, at some point the cook had simply cracked open the window to provide an escape route for the heat and the odors of cooking. It was a small kitchen, and perhaps she’d been instructed to keep the door to the dining room closed to spare the house’s inhabitants the smells of cabbage or cruciferous vegetables, the smoke of broiling meat. I can’t say the explanation made me completely happy, but I allowed it, combined with the money in hand and the money yet to come, to keep me from going straight out through the front door and across Koreatown to the apartment I shared with my girlfriend of more than a year now, Ronnie Bigelow. Ronnie and I needed the money. We were planning an operation to kidnap her two-year-old son from his father, a New Jersey mob doctor, and it was an expensive proposition.

The house chose that moment to creak, and I said to it silently, the hell with you. I’m in, and I’ll finish up and get out again. Twenty-five thousand bucks can muffle a lot of creaks.

The door at the far end of the kitchen opened, as expected, into a cramped servant’s bedroom with bare floors—concrete, not wood—and only one narrow window, placed so high by the room’s designers that it suggested they’d been afraid someone might escape through it. The room was empty except for a single bed, bare but for a thin, graying mattress and a couple of misshapen pillows. Sheets, none too clean, were neatly folded at the foot of the bed. The closet contained nothing but a tangle of coat hangers and a sharp smell of mouse urine, and when I checked the bathroom I found the barest of minimums: a sink, a claustrophobic shower, and a toilet containing water that would probably give me nightmares for weeks. The bathroom had neither a window nor a vent, which seemed like the cruelest economy of all.

Keeping the uncovered window in mind, I turned off the penlight as I moved through the kitchen, opening drawers and cupboards until I came upon a cupboard that was jammed solid with brown paper supermarket bags, undoubtedly to replace the ones masking the windows as they aged and tore. This had all the symptoms, I thought, of a full-blown mania. I closed everything and headed back into the dining room, staying close to the wall. I was most of the way to the hallway, when I was brought up short once again by the carpeting, or, rather, the lack of it. The dining room should have been carpeted. Since the windows in here were covered, I flicked on the light and played it around the room, and on the bare floor was a sparse huddle of junk: a Formica table on aluminum legs, three banged-up folding director’s chairs. Total value, maybe eighty-five bucks. Just to confirm my budding suspicion, I crossed the hall and took a look at the living room.

More rubbish furniture on the bare floor, and now I also saw the rectangles on the walls, slightly darker than the wallpaper, the ghosts of paintings that had hung there for decades. The only framed art pieces remaining in the room were a couple of gauzy sepia photographs, one on each side of the fireplace, at about eye level. They did not call out to me to take a closer look. Even the bookcases had apparently been ransacked, creating spaces on the shelves, the books on either side tilting left and right, looking depressed at having been left behind in the methodical disappearance of items of value.

So, unlike the window glass, unlike the house itself, the carpets, furnishings, and decorations had departed, to be replaced with crap—modern, cheap, and even a little battered. Much of it looked like the rag ends of yard sales, which is to say that it was not just used, but hard used. Some items might have sat outside in bad weather. And yet the house had never been rented out, as far as I knew, and the Hortons had never gone broke. The place was going to be razed presumably because the lot was worth more without the house on top of it, and none of the living Horton cousins wanted to live in it.

The missing carpets and the vanished furniture, with its bargain-basement replacements, suggested an appalling little playlet. Rich old woman immobilized upstairs. Downstairs, slow-motion, wholesale theft: sell a piece here, sell a piece there, and there, replace it with crap, knowing the next time Miss Daisy would come down the stairs and into these rooms, she’d be carried through them feet first. One immobilized woman, dependent on others for everything, a woman who had been born into a world where servants were seen as faithful retainers, practically “members of the family.” Living in service, dying in service, drawing satisfaction from their positions close to the rich and the near-rich, loving the family’s children like their own, taking pride in being part of a great house.

Had that ever been true? Couldn’t have been. At the very least, I supposed, it had been a notion that reassured the rich that the people who moved through the rooms while the family slept were unlikely to murder them in their beds. Despite that awful, airless little bedroom, that dire bathroom.

If I was reading the ground floor correctly, Miss Daisy had, for at least her last few years, lived upstairs from a skeleton crew of thieves who cashed in one Horton possession after another, possibly even working their way up the stairs and into the unoccupied rooms on the second floor as Miss Daisy’s world grew smaller until, at last, she’d been sentenced to spend the rest of her days in bed, the cradle waiting at the bad end of life, being turned and baby-powdered and, one hoped, comforted occasionally, while pieces of her life walked out the front door. She might have been an awful old rag—her reputation when she was younger, and the cold, closed nature of her house suggested that the solitude in which she lived had been well earned—but it was hard to imagine that she, or anyone, deserved that.

If the original things in these rooms had been the kind of quality appropriate to the house and the Hortons’ place in society, there had probably been more than a couple hundred thousand bucks’ worth on the first floor alone. And who knew what the pictures had been? Even if the people who sold the items had no sense of what they were worth, they’d still be thirty, forty thousand to the good.

And that thought stopped me with one foot on the bottom stair. If all those fine things had been stolen and sold, why in the world would the thing I was after still be here?

***

Buy from Your Local Bookstore | Buy from Barnes & Noble | Buy from Amazon | Buy from Soho Press