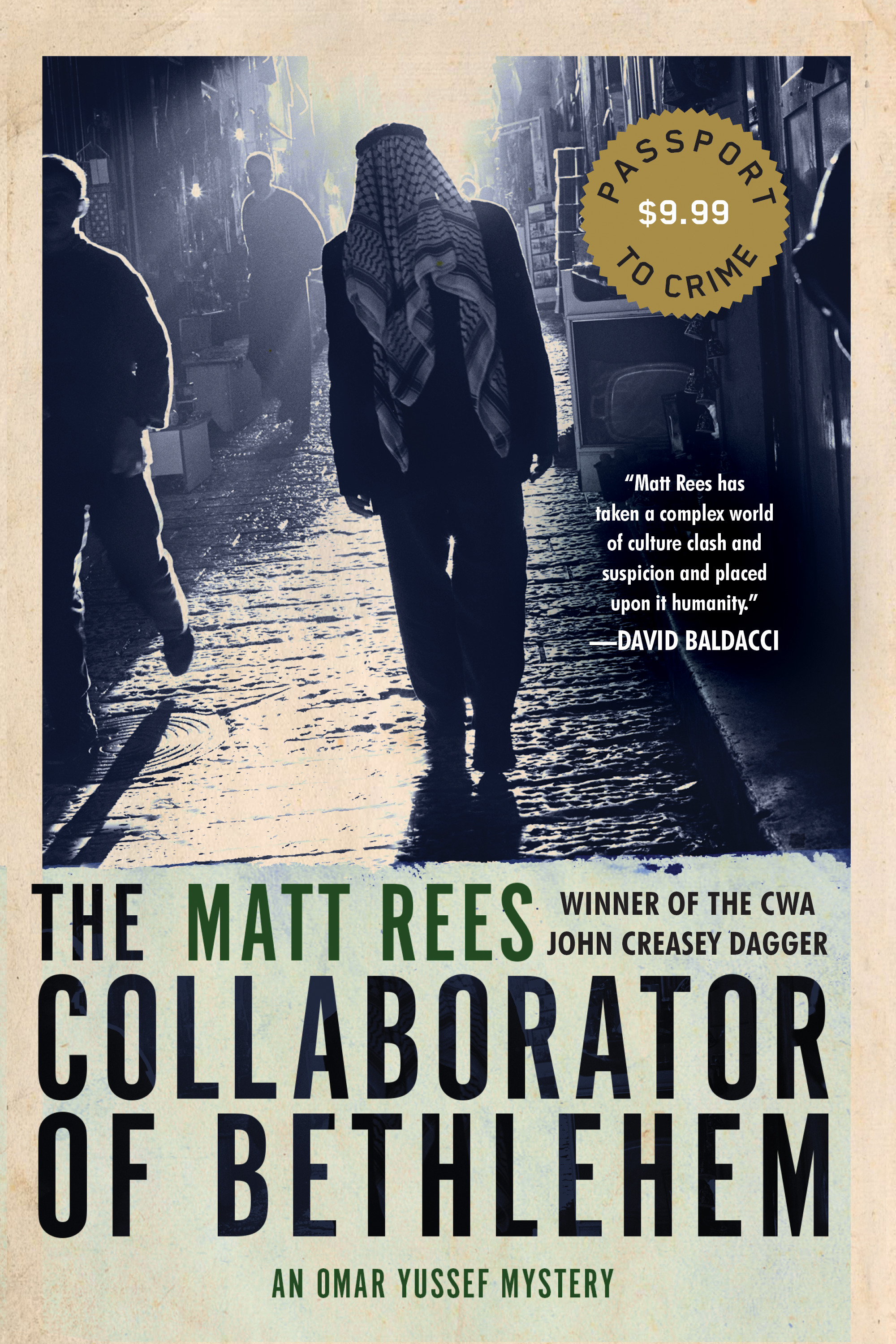

“Matt Rees has taken a complex world of culture clash and suspicion and placed upon it humanity.” –David Baldacci

Soho Crime has a deep, diverse backlist and it is always a joy to dip in and see what kind of gem turns up.

Such is the case this week as we gear up for the reissue of Matt Rees’ outstanding Collaborator of Bethlehem.

The book is a fast, smart thriller that satisfies on many levels and won the CWA John Creasey Dagger.

More about the book:

Omar Yussef has taught history in Bethlehem for decades. When a favorite former student, a member of the Palestinian Christian minority, is arrested for collaborating with the Israelis in the killing of a Palestinian guerrilla—a transgression with an inevitable death sentence—Omar is sure he has been framed. When Omar begins to suspect the head of the Bethlehem al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades is the true collaborator, he and his family are threatened, but since no one else will stand up to the violent Martyrs Brigades who hold power over the city, it is up to him to investigate.

All it takes is one good man—a detective, of course—to humanize events that confound understanding … An astonishing first novel … Setting a mystery in the epicenter of a war zone challenges the genre conventions, but it doesn’t change the rules. In fact, it clarifies the role of the detective as the voice of reason, crying to be heard above the cacophony of gun-barrel politics.” –New York Times Book Review

The Collaborator of Bethlehem is on sale for today only.

PB: $4.99

EB: $1.99

***

Read an Excerpt: Chapter 1

Omar Yussef, a teacher of history to the unhappy children of Dehaisha refugee camp, shuffled stiffly up the meandering road, past the gray, stone homes built in the time of the Turks on the edge of Beit Jala. He paused in the strong evening wind, took a comb from the top pocket of his tweed jacket, and tried to tame the strands of white hair with which he covered his baldness. He glanced down at his maroon loafers in the orange flicker of the buzzing street lamp and tutted at the dust that clung to them as he tripped along the uneven roadside, away from Bethlehem.

In the darkness at the corner of the next alley, a gunman coughed and expectorated. The gob of sputum landed at the border of the light and the gloom, as though the man intended for Omar Yussef to see it. He resisted the urge to scold the sentry for his vulgarity, as he would have one of his pupils at the United Nations Relief and Works Agency Girls School. The young thug, though obscured by the night, formed an outline clear as the sun to Omar Yussef, who knew that obscenities were this shadow’s trade. Omar Yussef gave his windblown hair a last hopeless stroke with a slightly shaky hand. Another regretful look at his shoes, and he stepped into the dark.

Where the road reached a small square, Omar Yussef stopped to catch his breath. Across the street was the Greek Orthodox Club.

Windows pierced the deep stone walls, tall and mullioned, capped with an arch and carved around with concentric rings receding into the thickness of the wall, just high enough to be impossible to look through, as though the building should double as a fortress. The arch above the door was filled with a tympanum stone. Inside, the restaurant was silent and dim. The scattered wall lamps diffused their egg-yolk radiance into the high vaults of the ceiling and washed the red checkered tablecloths in a pale honey yellow. There was only one diner, at a corner table below an old portrait of the village’s long-dead dignitaries wearing their fezes and staring with the empty eyes of early photography. Omar Yussef nodded to the listless waiter—who half rose from his seat—gesturing that he should stay where he was, and headed to the table occupied by George Saba.

“Did you have any trouble with the Martyrs Brigades sentries on the way up here, Abu Ramiz?” Saba asked. He used the unique mixture of respect and familiarity connoted by calling a man Abu—father of—and joining it to the name of his eldest son.

“Just one bastard who nearly spat on my shoe,” said Omar Yussef. He smiled, grimly. “But no one played the big hero with me tonight. In fact, there didn’t seem to be many of them around.”

“That’s bad. It means they expect trouble.” George laughed. “You know that those great fighters for the freedom of the Palestinian people are always the first to get out of here when the Israelis come.”

George Saba was in his mid-thirties. He was as big, unkempt and clumsy as Omar Yussef was small, neat and precise. His thick hair was striped white around the temples and it sprayed above his strong, broad brow like the crest of a stormy wave crashing against a rock. It was cold in the restaurant and he wore a thick plaid shirt and an old blue anorak with its zipper pulled down to his full belly. Omar Yussef took pride in this former pupil, one of the first he had ever taught. Not because George was particularly successful in life, but rather for his honesty and his choice of a career that utilized what he had learned in Omar Yussef’s history class: George Saba dealt in antiques. He bought the detritus of a better time, as he saw it, and coaxed Arab and Persian wood back to its original warm gleam, replaced the missing tesserae in Syrian mother-of-pearl designs, and sold them mostly to Israelis passing his shop near the bypass road to the settlements.

“I was reading a little today in that lovely old Bible you gave me, Abu Ramiz,” George Saba said.

“Ah, it’s a beautiful book,” Omar Yussef said.

They shared a smile. Before Omar Yussef moved to the UN school, he had taught at the academy run by the Frères of St. John de la Salle in Bethlehem. It was there that George Saba had been one of his finest pupils. When he passed his baccalaureate, Omar Yussef had given him a Bible bound in dimpled black leather. It had been a gift to Omar Yussef’s dear father from a priest in Jerusalem back in the time of the Ottoman Empire. The Bible, which was in an Arabic translation, was old even then. Omar Yussef’s father had befriended the priest one day at the home of a Turkish bey. At that time, there was nothing strange or blameworthy in a close acquaintance between a Roman Catholic priest from the patriarchate near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem and the Muslim mukhtar of a village surrounded by olive groves south of the city. By the time Omar Yussef gave the Bible to George Saba, Muslims and Christians lived more separately, and a little hatefully.

Now, it was even worse.

“It’s not the religious message, you see. God knows, if there were no Bible and no Koran, how much happier would our troubled little town be? If the famous star had shone for the wise men above, let’s say, Baghdad instead of Bethlehem, life would be much brighter here,” Saba said. “It’s only that this Bible in particular makes me think of all that you did for me.”

Omar Yussef poured himself some mineral water from a tall plastic bottle. His dark brown eyes were glassy with sudden emotion. The past came upon him and touched him deeply: this aged Bible and the learned hands that left the grease and sweat and reverence of their fingertips on the thin paper of its dignified pages; the memory of his own dear father who was thirty years gone; and this boy whom he had helped shape into the man before him. He looked up fondly and, as George Saba ordered a mezze of salads and a mixed grill, he surreptitiously wiped his eyes with a fingertip.

They ate in quiet companionship until the meat was gone and a plate of baklava finished. The waiter brought tea for George and a small cup of coffee, bitter and thick, for Omar.

“When I emigrated to Chile, I kept the Bible you gave me close always,” George said.

The Christians of George’s village, Beit Jala, had followed an early set of emigrants to Chile and built a large community. The comfort in which their relatives in Santiago lived, worshipping as part of the majority religion, was an ever-increasing draw to those left behind, sensing the growing detestation among Muslims for their faith.

In Santiago, George had sold furniture that he imported from a cousin who owned a workshop by the Bab Touma in Damascus: ingeniously compact games tables with boards for backgammon and chess, and a green baize for cards; great inlaid writing desks for the country’s new wine moguls; and plaques decorated with the Arabic and Spanish words for peace. In Chile, he married Sofia, daughter of another Palestinian Christian. She was happy there, but George missed his old father, Habib, and gradually he persuaded Sofia that now there was peace in Beit Jala and they could return. He admitted that he was wrong about the peace, but was glad to be back anyway. He had seen Omar Yussef here and there since he had brought his family home, but this was their first chance to sit alone and talk.

“The old house is the same as ever, filled with racks of Dad’s wedding dresses. The rentals in the living room and those for sale in his bedroom, all wrapped in plastic,” George Saba said. “But now they’re almost crowded out by my antique sideboards from Syria and elaborate old mirrors that don’t seem to sell.”

“Mirrors? Are you surprised that no one should be able to look themselves in the eye these days?” Omar Yussef sat forward in his chair and gave his choking, cynical laugh. “They lead us further into corruption and violence every day, and no one can do anything about it. The town is run by a shitty tribe of uneducated bastards who’ve got the police scared of them.”

George Saba spoke quietly. “You know, I’ve been thinking about that. The Martyrs Brigades, they come up here and shoot across the valley at Gilo, and the Israelis fire back and then come in with their tanks. My house has been hit a few times, when the bastards did their shooting from my roof and drew the Israeli fire. I found a bullet in my kitchen wall that came in the salon window, went through a thick wooden door and traveled down a hallway, before it made a big hole in my refrigerator.” He looked down and Omar Yussef saw his jaw stiffen. “I won’t let them do it again.”

“Be careful, George.” Omar Yussef put his hand on the knuckles of George Saba’s thick fingers. “I can say what I feel about the Martyrs Brigades, because I have a big clan here. They wouldn’t threaten me, unless they were prepared to face the anger of half of Dehaisha. But you, George, you’re a Christian. You don’t have the same protection.”

“Maybe I’ve lived too long away from here to accept things.” He glanced up at Omar Yussef. There was a raw intensity in his blue eyes. “Perhaps I just can’t forget what you taught me about living a principled life.”

Omar Yussef was silent. He finished his coffee.

“You know who else has returned to Bethlehem from our old crowd?” George Saba’s voice sounded tight, straining to lighten the tone of the conversation. “Elias Bishara.”

“Really?” Omar Yussef smiled.

“You haven’t seen him yet? Well, he’s only been back a week. I’m sure he’ll stop by your house once he’s settled in.”

Younger than George Saba, Elias Bishara was another of Omar Yussef’s favorite pupils at his old school. “Wasn’t he studying for a doctorate in the Vatican?” Omar Yussef asked.

“Yes, but since then he’s been living in Rome as some kind of apostolic secretary to one of the cardinals. Now he’s back at the Church of the Nativity. I know, Elias and I are only asking for trouble by coming home, Abu Ramiz. Perhaps you can’t understand what it has been like for us. We grow up in this dismal place, wanting desperately to leave for another country where we can make money and live in peace. But the day always comes when you imagine the savor of real hummus and the intoxicating brightness of the sun on the hills and the sound of the church bells and the muezzins. You miss it so much you can taste the longing on your tongue. Then you come back, no matter what it is you are giving up. You just can’t help it.”

“I’ll go to the Church and say hello to Elias as soon as I get a chance.”

“Next month is Christmas, so I wanted to invite you to come with us to the Church to celebrate,” George said. “And then you and Umm Ramiz will come for Christmas dinner at my house.”

“I would be delighted, and so will she, too.”

The two men argued over who should pay the check. Both threw money onto the table and picked up the other’s cash to force it back into his hand. Then the shooting began. It was close enough that it sounded big and hollow, not like the whipcrack of faraway firing.

George looked up. “Those sons of whores, they’ve started again.” He stood, leaving his cash on the table. “Abu Ramiz, I have to go.”

They went to the door. Omar Yussef could see the tracer striping across the valley toward a house along the street. The big, bass bursts of gunfire from the village were directed toward the Israelis in the Jerusalem suburb over the wadi. The gunfire emanated from the roof of a square, two-story house only fifty yards away. There was a dark Mitsubishi jeep in the lee of the building. George Saba stepped into the street. “Jesus, I think they might be on my roof again.”

“George . . .”

“Don’t worry about me. Get out of here before the Israelis come. Not even your big clan will protect you from them. Goodbye, Abu Ramiz.” George Saba put an affectionate hand on Omar Yussef’s arm, then went fast along the street, bending low behind the cover of the garden walls.

Omar Yussef put his hands over his ears as the Israelis switched to a heavier gun. It shot tracers that left a deceptively slow, dotted line in the darkness, like a murderous Morse Code. That code spelled death, and the warmth that he had felt during the dinner left Omar Yussef. He could no longer see George Saba. He wondered if he should follow him. The waiter stood nervously behind him in the doorway, eager to lock up. “Are you coming inside, uncle?”

“I’m going home. Good night.”

“May God protect you.”

Omar Yussef thought he must have looked foolish, groping his way along the wall at the roadside, kicking his loafers in front of him with every step to be sure of his footing on the broken pavement. An awareness of fear and doubt came over him. He sensed movement in the alleys he passed, and shadows momentarily took on the shape of men and animals, as though he were a frightened child trying to find the bathroom in the darkness of a nighttime house. He was sweating and, where the perspiration gathered in his mustache and on the baldness of his head, the night wind chilled him. What an old fool you are, he told himself, scrambling about in a battle zone in your nice shoes. Sometimes you can have a gun to your head and you still don’t know where your brains are.

The firing behind him grew more intense. He wondered what George Saba might do if he found the gunmen on his own roof again, and he decided that only when a gun points at your heart do you realize what it is that you truly love.

George Saba’s family huddled against the thick, stone wall of his bedroom. It was the side of the house farthest from the guns. George came through the front door. The shooting was louder inside and he realized the bullets were punching through the windows into his apartment. He ducked into an alcove in the corridor and crouched against the wall. At the back of the house, his living room faced the deep wadi. It was taking heavy fire from the Israeli position over the canyon.

Sofia Saba stared frantically across the corridor at her husband. She was not quite forty, but there were lines that seemed suddenly to have appeared on her face that her husband had never noticed before, as though the bullets were cracking the surface of her skin like a pane of glass. Her hair, a rich deep auburn dye, was a wild frame for her panicked eyes. She held her son and daughter, one on either side of her, their heads grasped protectively beneath her arms. All three were shaking. Next to them, Habib Saba sat silent and angry, below the antique guns mounted decoratively on the wall by his son. His cheekbones were high and his nose long and straight, like an ancient cameo of some impassive noble. Despite the gunfire, he held his head steady as an image carved from stone. George called out to his father above the hammering of the bullets on the walls, but the old man didn’t move.

Most of the Israeli rounds struck the outside wall of the living room with the deep impact of a straight hit. These were no ricochets. Every few moments, a bullet would rip through the shattered remains of the windows, cross the salon and embed itself in the wall behind which George Saba’s family sheltered. Sofia shuddered with each new impact, as though the projectiles might take down the entire wall, picking it away chunk by chunk, until it left her children exposed to the gunfire. The hideous racket of the bullets was punctuated by the sounds of mirrors and furniture falling in the living room and porcelain dropping to the stone floor from shattered shelves.

A bullet rang down the corridor and splintered the wood of the front door through which George Saba had entered. As he had dodged along the road in the darkness, he had been determined that tonight he would act. He had cursed the gunmen under his breath, and when a shot struck particularly close to him he had sworn at the top of his voice. Now he wanted only to crawl deeper into the alcove, to dig himself inside the wall until this nightmare stopped. If he stayed in the niche long enough, perhaps he would awake and find himself in his store in Santiago and this idiotic fantasy of returning to his childhood home would once more be merely a dream, not a reality of red-hot lead, blasting through his home, destructive and deadly. He looked over to the bedroom and caught his wife’s pleading expression, as she struggled to keep the heads of their children hidden beneath her arms. He wasn’t going to wake up in Chile. He couldn’t hide. He had to end this. He got to his feet, sliding up the wall, pushing his back hard against it as though it might wrap his flesh in impenetrable stone. He took the tense, expectant breath of a man dropping into freezing water and dashed across the exposed corridor into the bedroom.

George Saba hugged his wife and children to him. “It’s going to be all right, darlings,” he said. “I’m going to take care of it.” He pulled them close so they wouldn’t see that his jaw shook.

For the first time, his father moved his head. “What are you going to do?”

George looked sadly at the old man. He wasn’t fooled by the stillness with which Habib Saba held himself. It wasn’t calm and resolve that kept the old man frozen in his self-contained posture against the wall. His father cowered in the bedroom because he was accustomed to the corruption and violence of their town. He lived as quietly and invisibly as he could, because Christians were a minority in Bethlehem, and so Habib Saba was careful not to upset the Muslims by standing up to them. George had learned a different way of life during his years away from Palestine. He put his hand on his father’s shoulder and then touched the old man’s rough cheek.

Quickly, George stood and reached for an antique revolver mounted on the wall. It was a British Webley VI from the Second World War that he had bought a few months before from the family of an old man who had once served in the Jordanian Arab Legion and kept the gun as a souvenir of his English officers. The gray metal was dull and there was rust on the hinge, so that the cylinder couldn’t be opened. But in the darkness its six-inch barrel would look deadly enough, unlike the three inlaid Turkish flintlocks that decorated the bedroom wall beside it. George Saba tightened his hand around the square-cut grip and felt the gun’s weight.

Habib reached out for his son’s arm, but couldn’t hold fast. Sofia screamed when she saw the revolver in her husband’s hand. At the sound, her daughter peered from under her mother’s arm. George knew he must act now or the sight of those frightened eyes would break him. He reached down and put his hand over the child’s brow, as though to close her eyes. “Don’t worry, little Miral. Daddy’s going to tell the men to stop playing and making noise.” It sounded stupid and, for the moment, he kept his fingers over the girl’s face so that he wouldn’t see the look of incredulity he felt sure would have registered on her features. Even a child could tell this was no game. Then he dashed through the front door.

***

“Rees tells this grim story with skill, specificity and richly detailed descriptions of people and places.” – The Washington Post

On sale today only.

PB: $4.99

EB: $1.99