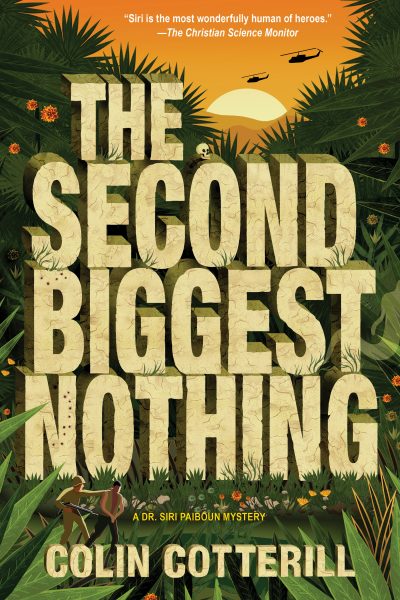

The fourteenth installment in the Dr. Siri Paiboun mysteries is here! Join “the most wonderfully human of heroes,” Dr. Siri Paiboun, in Communist Laos in the early ’80s, a time and place evoked in only the way Colin Cotterill could: skillfully, magically, and spookily. In this quirky and critically acclaimed novel, a death threat sends Dr. Siri down memory lane–all the way from Paris in the ’30s to war-torn Vietnam in the ’70s–to figure out who’s trying to kill him in his present.

Vientiane, 1980: For a man of his age and in his corner of the world, Dr. Siri, the 76-year-old former national coroner of Laos, is doing remarkably well—especially considering the fact that he is possessed by a thousand-year-old Hmong shaman. That is, until he finds a mysterious note tied to his dog’s tail. Upon finding someone to translate the note, Dr. Siri learns it is a death threat addressed not only to him, but to everyone he holds dear. Whoever wrote the note claims the job will be executed in two weeks.

Thus, at the urging of his wife and his motley crew of faithful friends, Dr. Siri must figure out who wants him dead, prompting him to recount three incidents over the years: an early meeting with his lifelong pal Civilai in Paris in the early ’30s, a particularly disruptive visit to an art museum in Saigon in 1956, and a prisoner of war negotiation in Hanoi at the height of the Vietnam War in the ’70s. There will be grave consequences in the present if Dr. Siri can’t decipher the clues from his past.

Find out in The Second Biggest Nothing: on sale wherever books are sold!

1

A City of Two Tails

Dr. Siri was standing in front of Daeng’s noodle shop when she pulled up on the bicycle. It was a clammy day, but his wife rarely raised a sweat even under a midday sun. She leaned the bike against the last sandalwood tree on that stretch of the road and patted Ugly the dog. Siri shrugged.

“So?” he said.

“So what?”

“What did she say?”

Daeng pecked him on the cheek and walked past him into the dark shop house. He trotted behind.

“She said I have the body and constitution of a sixty- nine-year-old.”

“You are sixty-nine.”

“Then I have nothing to be disappointed or smug about, do I? I’m fit and healthy. I’m a nice, average Lao lady with supposed arthritis. She did, however, mention that most people my age in this country are dead. I think that’s a positive, don’t you?”

“But what about . . . ? You know?” “She didn’t say anything,” said Daeng. “She what?”

“Didn’t mention it at all. She obviously didn’t notice it.” “What kind of a doctor doesn’t notice that one of her patients has a tail?”

“I’ve told you, Siri. You and I are the only people who see it.” “What about the shamans in Udon?”

“They didn’t see it, Siri. They visualized it. Not the same thing.”

“It’s a physical thing, Daeng. You know it is. I can feel it.” “I know. And I like it when you do.”

“But now Dr. Porn would have us believe that it doesn’t exist, which means I must be senile,” said Siri.

“It means we’re both senile.”

“Then, by the same account, if you don’t have a tail, then obviously my disappearances are a figment of my imagination.”

“Not at all,” said his wife dusting the stools to prepare for the evening noodle rush. “All it tells us is that nobody else notices you’re gone.”

“I’ve disappeared in public before,” said Siri with more than a touch of indignation. “Haven’t I disappeared in the market? At a musical recital? In a crowded—”

“Look, my love,” she said, taking his hand, “there is no doubt that you disappear. There is no doubt you cross over to the other side and learn things there and return and tell me of your adventures. There is no doubt you are possessed by a thousand-year-old Hmong shaman and communicate through an ornery transvestite spirit medium. There is no doubt that you see the souls of the dead just as there is no doubt that I have a tail that I received from a witch in return for a cure for my arthritis. But, for whatever reason, nobody else bears witness to our little peculiarities. And perhaps it’s just as well. The politburo would probably have us burned at the stake for occult practices if anyone reported us. Even Buddhism makes them queasy. Imagine what they’d do if Dr. Porn wrote in her official report, ‘. . . and, by the way, Madam Daeng appears to have grown a tail since her last checkup.’”

“You’re right,” said Siri.

“I’m always right,” said Daeng. She squeezed his hand and smiled and returned to the chore of readying her restaurant. She was startled by the sound of hammering from the back room.

“What’s that?” she asked. “Nyot, the doorman,” said Siri.

“He’s still here?” asked Daeng. “How long does it take to put in a door?”

Mr. Nyot, the carpenter, was busy hanging. Following the previous monsoons, the door had changed shape and would no longer close. Daeng was not afraid of intruders. Ever since it was installed when the shop house was rebuilt, that door had never been locked. Nobody could remember where the key was. There were no security issues in Vientiane. The Party wouldn’t allow such a thing. All the burglars were safely behind bars on the detention islands. The ill-fitting door banged in the wind and Mr. Nyot had promised them a nice new door at a special price. But it was also a special door. Daeng went to inspect the work.

“What’s that?” she asked, pointing at the missing rectangle of wood at the base.

“It’s a dog entrance,” said Nyot. “It’s a hole,” said Daeng.

“Right now it may look like a hole,” said Nyot, “but over there I have a flap with hinges that I will attach shortly.”

“That’s not what I ordered,” said Daeng.

“Maybe not. But this door is five-thousand kip cheaper than the next in the range. And I did notice that you have a dog outside that seems unable to enter the building.”

“That dog has never entered a building,” said Daeng. “Not because it’s unable to but because it has some canine dread of being inside.”

“Well, when it gets over its fear this will be the perfect door for it.”

She couldn’t be bothered to argue and the saved five-thousand kip would come in handy even though it was a tiny sum. But she was sure that when the wind blew from then on, the dog flap would bang through the night and the hinges would creak and they would miss their old one. She was very pessimistic when it came to doors.

Siri laughed at their exchange as he wiped the tabletops with a dishcloth and thought back to his last contact with Auntie Bpoo, his unhelpful, unpleasant spirit guide. It had been a while. She had him on some kind of training program. He’d passed “taking control of his own destiny” and “awareness,” and he was ready for the next test but for some reason she’d gone mute. He attempted to evoke her often, but the channel was off air. Often, he wished his life could have been, not normal exactly, but more under his own control. Daeng was saying something behind him.

“What was that?” Siri asked.

“I said the ribbon was a nice touch,” said Daeng. “What ribbon’s that?”

“You didn’t decorate the dog?”

“Not sure I know what you’re talking about.”

“The ribbon, Siri. You didn’t see him out there? Ugly has a rather sweet pink bow on his tail.”

“Nothing to do with me,” he said walking to the street. Ugly was under the tree guarding the bicycle. Sure enough, he was wearing a ribbon with a silk flower, and from the rear he looked like a mangy birthday present.

Siri laughed. “This looks like the work of a certain Down syndrome comedian I know,” he said.

“Can’t blame Geung and his bride this time,” said Daeng. “In case you haven’t noticed, we’re doing all the noodle work here. He and Tukta won’t be back from their honeymoon for another week. And Ugly was not so beautifully kitted out when I left this morning. Don’t take it off. He looks adorable.”

Siri was bent double inspecting the dog’s rear end. There was more of a sausage than an actual tail so it was surprising the decorator had found enough length to tie on the bow and that Ugly would allow it.

“It appears to have a message attached,” Siri said. “There’s a small capsule hanging from it. Lucky he didn’t need to go to the bathroom before you noticed it.”

“A message?” She smiled. “How thrilling.”

Never one to pass up a mystery, Daeng joined her husband on the uneven pavement. Ugly seemed reluctant to give up his treasure. He growled deep in his throat.

“Come on, you ungrateful mongrel,” said Siri. “Who do you think pays for your meals and applies ointment to all your sores and apologizes to the neighbors for your indiscriminate peeing?”

It was a compelling argument and one that Ugly obviously had no counter for. He held up his haunches for his master to remove the capsule. It was a silver cylinder about the size of a cigarette. Its two halves could be pulled apart. Siri had seen its kind before but he couldn’t remember where. Inside was a tight roll of paper, which he unfurled.

“Unquestionably a treasure map,” said Daeng.

“Only words, I’m afraid,” said Siri. “And handwritten.” Still pretending that his eyesight was as good as it had always been, he held out the slip at arm’s length and squinted at the tiny writing. He would blame that arm for its shortness rather than admit to any deficiency in his eyesight. The note was just within range. “It’s in English,” he said.

“What a shame,” said Daeng.

He read it aloud with what he considered to be an English accent.

“My dear Dr. Siri Paiboun, it has been a while. By now I’m sure you have either forgotten my promise of revenge or have dismissed it as an idle threat. But if you had known me at all, you would have realized that my desire to destroy you and your loved ones is a fire that has burned in my heart without end. After such a long search I have found you and I am near you. I have already deleted one of your darlings. Before I leave I will have ruined the life you have established just as you did mine. I have two more weeks. That should be more than sufficient.”

It would be several hours before Siri and Daeng could fully appreciate the seriousness of their note because neither of them understood English. They knew French and could read the characters and they could guess here and there at meanings. But the languages were too far apart to cause either of them to panic. That would come later.

2

The Glory of Totalitarianism

At the end of 1980, Vientiane was a city still waiting for something to happen. It had waited through the droughts and floods, through the flawed policies, the failed cooperatives, the mass exodus of the Hmong and lowland Lao and, more recently, ethnic Chinese business holders across the Mekong. It had waited for inspiration, for good news, for a break. It had been waiting for five years but still nothing of any note had happened. So, what better way to celebrate five years of Communist rule than by inviting a large number of foreign journalists to observe the results of all those things that hadn’t happened? There were those who argued that nothing was a good thing. For thirty years the Lao had been waging a war against their brothers and against the foreign powers that put them in uniforms. Wasn’t nothing better than that?

It was what they called “a cocktail reception” even though none of the glasses being carried around on silver trays contained anything more exotic than weak whisky sodas and room temperature white wine. The hostesses who carried the trays wore thick makeup, military uni- forms and uncomfortable boots. They smiled in a way that suggested they were under orders to do so. They did not enter into conversation with the already soused foreign journalists because they could not. They were from villages in distant provinces and even fluency in the Lao language was beyond their linguistic ability. And they had been warned by their superiors about these men from the decadent West and the shady East who bit the heads off babies and had sexual organs the size of ripe papayas. The girls trembled at every flirtatious glance, each beckoning whistle.

In its day, the nightclub of the Anou Hotel had been a gloomy cavern of nefarious goings on. When first the French, and then the American soldier boys played there, it was a mysterious grotto, so dark you couldn’t see the age of your dance partner, so heavy with marijuana smoke you couldn’t smell the fluids that had soaked into the carpets the night before. But on this evening, this glorious eve- ning that marked the fifth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos, the lights were all on, and there were no secrets. The gaps in the parquet tiles on the dance floor had been filled with cement and painted brown. The table vinyl curled up at the edges, and the light-blue paint peeled from the beams.

But, as Comrade Civilai said, perhaps this was the symbolism the Party wanted to pass along to the world. The decadent past had fallen into ruination. The last altars to the gods of depravity were crumbling and turning to dust. “Or,” Civilai added, “perhaps there was no other venue

with a functioning sound system and a full bar.”

Since he left the politburo he’d not been sure of the motives behind Party policy. Perhaps he never had.

Intimacy was obviously another government plot to endear itself to the outside world. There really wasn’t a great deal of space in the Anou. Sixty-four foreign journalists—all male—were shoulder to shoulder with Russian interpreters, most of the resident diplomatic community, selected aid workers and donors and the UN, even though nobody was ever really sure what the latter did to earn their living in Laos. All of the ministries were represented, each minister and vice minister with his own aide to help carry him back to the Zil limo at the end of the night.

Comrade Civilai—wearing cool, avant garde sunglasses— was there because of his distinguished service to the cause of communism in Laos and his apparent undying loyalty to the politburo. Chief Inspector Phosy was there because, despite several attempts to oust him by those who had become accustomed to graft and corruption, he was still the head of the police force. His wife, Nurse Dtui was there because it was a perfect opportunity to practice the foreign languages she’d taught herself with little or no benefit thus far. And Dr. Siri and Daeng were there because it was walking distance from their restaurant and a nice evening. They hadn’t been invited, but no scruffy sentry with an unloaded AK-47 was going to turn away such a distinguished white-haired couple.

This small group of friends and allies sat at a table near the exit. They’d tired of attempting to snare any of the reluctant hostesses and instead had relieved the open bar of a half bottle of Hundred Pipers. With it they toasted anything that came to mind: to the miracle that they were all still alive, to Geung and Tukta on their honeymoon at a small vegetable cooperative outside Vang Vieng, to the peaceful, almost ghostly quiet streets of Vientiane, to the dizzying figure of 15 percent Lao literacy announced that afternoon, and, finally, to friendship. The bottle was approaching empty. Civilai had made more than his usual number of bladder runs to the bathroom because he’d hit a bad patch of stomach troubles following experiments with Lao snails in fermented morning glory sauce. The comrade was a pioneer in the kitchen and pioneers stepped on their own rabbit traps from time to time.

“What I don’t understand . . .” said Siri.

“There must be such a lot,” said Civilai, returning from the crowded toilet.

“I’m serious about treating this condition of yours,” said Siri.

“I’m not letting you and your rubber glove anywhere near my condition, thank you, Doctor,” said Civilai.

“Then, what I don’t understand,” Siri tried again, “is the significance of five years. Nine I can appreciate. Always been a lucky number. And ten has some decimal roundness to it. But five?”

“Well, young brother, it’s quite simple,” said Civilai. “The government is celebrating five years because, despite all its mismanagement and false hopes and poor judgment, it’s still here. They never expected to make it this far.”

“Who’s going to kick them out?” said Daeng.

“Exactly,” said Civilai. “That’s the glory of totalitarian- ism. You can screw up for five years and admit you have no idea what you’re doing and you wake up the next morn- ing and you’re still in power. You can experiment all over again.”

“If you weren’t suffering from dementia I’d arrest you for treasonous rhetoric,” said Phosy.

“Look around, young chief inspector,” said the old politburo man. “Point me out one minister or vice minister here who isn’t demented. All those grenades exploding too close to their brains.”

“Uncle Civilai, you seem particularly nasty tonight,” said Nurse Dtui. “Is it the snails?”

They charged their glasses and toasted to the snails. “In a way, yes,” said Civilai. “I’ll tell you, sweet Dtui.

Today, with no warning, no request, no discussion, I received a copy of the speech they expect me to give to all these pliable journalists at the end of the week.”

“You could always say ‘no,’” said Siri.

“And then what? They’d give the same script to some other doddery old fool to read the lies.”

“So what are you planning to do?” Daeng asked. “Harness the power of redaction,” said Civilai.

“You’d get two minutes into the speech and they’d drag you from the podium,” said Phosy.

“But what a glorious two minutes they would be,” said Civilai.

“Except the simultaneous interpreters will be reading the original script,” said Daeng. “The old king tried to change his abdication speech, and the radio station brought in an actor to read the Party version.”

“An actor we could sorely use right now,” said Siri, anxious to change the subject.

“I still have the floor,” said Civilai.

“Oh, right,” said Nurse Dtui, ignoring him, “your movie.

I was going to ask about that. Don’t you have a cast yet?” “I feel nobody takes me seriously anymore,” Civilai grumbled.

“The Women’s Union has brought together a vast gaggle of would-be performers,” said Siri.

“All we’re missing is a functioning camera,” said Daeng. “The camera is functioning,” said Siri, “and we are on the verge of acquiring a world-class cinematographer to operate it.”

“Here I am about to re-educate the planet,” said Civilai, “and you dismiss my plan out of hand.”

“Perhaps we aren’t yet drunk enough to take you seriously,” said Daeng. “Another bottle might persuade us.”

Civilai huffed and the hairs in his nostrils flapped. He walked off to the bar with a heavy smattering of umbrage and a noticeable stagger.

“He’s not really going to sabotage the speech, is he?” Nurse Dtui asked.

“He’s a politician,” said Siri.

He’d planned to say more but realized that short phrase said it all.

“And the camera story?” asked Phosy.

The camera in question was a very expensive Panavision Panaflex Gold which had become ‘lost’ during the shooting of a film called The Deer Hunter in Thailand. Through the rice-growing underground it found its way to Laos and into the spare room on the upper floor of Madam Daeng’s restaurant. Until then, all it lacked was someone with the ability to turn it on. But that small setback to the filming of Dr. Siri’s ambitious Lao spectacular was apparently resolved.

“Our cinematographer has arrived and will begin his duties this weekend,” said Siri with a smile. “Daeng and I and various relatives went to the airport to greet him and make sure he didn’t change his mind and get on the return flight.”

“And by ‘cinematographer,’” said Daeng, “what Siri means is a young boy with a certificate in film production and no experience.”

“Yet more experience than all of us in the operation of a camera,” said Siri. “I was born into a generation of candles and beeswax lamps. Electricity entered my life late. It wasn’t until I arrived in Paris that I discovered the magic of volts and ampères. But by then I had decided to dedicate my life to medicine. If I had not, who’s to say by now I wouldn’t have been the one to invent the cassette player and the Xerox machine?”

“Is he legal, this camera person of yours?” the chief inspector asked.

“He’s Lao,” said Siri, “the cousin of Seksak who runs the Fuji Photo Lab. He’s harking the call of the Party for its lost sons to come home to the motherland to share their new skills and savings.”

“He left in the ’75 exodus?” Dtui asked.

“Before,” said Siri. “He made an orderly exit about ten years before with his father. Dad had a scholarship from the Colombo Plan. His wife died in childbirth, so it was just the two of them. They moved to Sydney. Bruce went to—”

“His name’s Bruce?” said Dtui.

“His father renamed him when they got there,” said Siri, “perhaps in an attempt to hide him amidst all the other Bruces. The boy had studied with the Australians here and become proficient in English. He sailed through high school and entered college.”

“Why would he ever want to come back?” Phosy asked.

“His cousin believes he was disillusioned with the decadent West. His father had been killed in a car accident in Australia and Bruce was homesick. Missed his distant family. When our government announced we’d welcome expatriate Lao with no hard feelings, he was only too keen. His cousin told him about our film. He read my script and was delighted to join us.”

“Can you afford him?” asked Dtui.

“Said he was happy to do it for nothing.”

“Must be mad,” said Civilai, returning with another half bottle of whisky, which he plonked down on the table like a memento of war.

“You could talk the crutches off a legless man,” said Daeng. “How do you do it?”

“Those young fellows just need to know who’s boss,” said Civilai. “Look important. Don’t say anything. Walk behind the bar. Pick up the bottle. Simple.”

He sat at the table, his revolutionary fire apparently doused.

“And speaking of who’s boss,” said Daeng, “where’s Madam Nong this evening?”

“My wife does not enjoy watching me drink,” said Civilai. “She seems to think I devalue myself when I allow alcohol to make decisions for me.”

“Whereas Madam Daeng here knows only too well that I am at my brightest and most perceptive with the Hundred Pipers playing the background music,” said Siri.

“Sadly, as the music grows louder and the perception reaches a crescendo, the passion is known to wane,” said Daeng.

There was a long silence at the table.

“We all know this is Daeng making a joke, right?” said Siri.

“I’m not so sure,” said Dtui. “Daeng, tell them,” said Siri.

Daeng looked around the room. “Daeng?”

The embarrassment was blurred by the voice of some- body leaning too closely into a badly wired microphone. Like announcements at the national airport, nobody knew exactly what had been said. But it was the signal for Siri’s crew to down their drinks and head to the exit. It was speech time and their finely tuned instincts naturally sent them in the opposite direction.

It was only a short walk to the noodle shop, but Siri must have told them a dozen times that his wife was joking about his waning ardor. Still she kept mum and they were all shedding tears of laughter by the time they reached the closed shutter. High in a tree opposite perched Crazy Rajhid, the Indian. They could only see his silhouette against the moon, but it was obvious he was as naked as on the day he was born. They waved. He ignored them. He still believed that if he kept perfectly still he was invisible.

It was the time of the evening when the dusty streets were usually deserted and no other sound could be heard: no television, no radio, no hum of air-conditioning. But on that evening their drunken voices were carried across the river to Thailand to show the enemy that socialist Laos could still have a good time once in a while. In an hour, when the curfew took hold, their voices would be silenced too, but right now was as good a time as any to stand on the riverbank and yell abuse. It was nothing personal, just a friendly diatribe against a nation with an ongoing animosity toward their inferior northern neighbors. It was therapy.

Once in the restaurant, Madam Daeng made a batch of noodles to soak up the whisky and put something in everyone’s stomach for the ride home. Only Civilai, still blaming the snails, forwent the meal.

“I think we need to approach the girl,” he said. “What girl’s that?” Phosy asked.

“The blonde,” said Civilai. “Acting second secretary at the American embassy. Looks gorgeous. Speaks fluent Lao. She was standing at the bar. I’ve met her at a few functions recently.”

“He has these hallucinations,” said Siri.

“In a room with two hundred men you really didn’t notice one attractive woman?” Civilai asked.

“Even in a room with two hundred women I’d only notice Daeng,” said Siri.

Daeng smiled and squeezed his hand.

“I was making all that up about his ardor,” she said.

“At last,” said Siri. “Why do you feel the need to approach the blonde, Civilai?”

“She has acting experience,” said Civilai. “We need her for the film.”

“In what role?” Siri asked. “Ours is the story of the nation through the eyes of two young revolutionaries not unlike ourselves. How many pretty blonde Americans fea- tured in the birth of the republic?”

“We could write in a part for her,” said Civlilai. “As what?”

“I don’t know. She could be the CIA.” “All by herself?” asked Siri.

“Why not?”

“I think you’ll find most women in the CIA back then were making coffee and typing,” said Madam Daeng.

“Look, it doesn’t matter what she does,” said Civilai.

“How many commercially successful movies have you seen that didn’t have a glamour interest?”

“I believe we have one or two beautiful Lao women in major roles,” said Dtui.

“That is admirable,” said Civilai. “But if we’re aiming at the international market . . .”

“Lao women aren’t attractive enough?” said Daeng. “They . . . you are lovely in the domestic sense,” said

Civilai, “but we need sexy. We need . . . we need a Barbarella.”

Only Siri and Civilai knew who Barbarella was, and Siri wasn’t about to disagree with his friend’s choice. There followed a testy five minutes as the old boys tried to define sexy and explain why even the most attractive Lao in her finest blouse and ankle-length phasin skirt would not qualify. They dug themselves deeper into the muck with every comment. The discomfort was only eased when Civilai felt the need for one more visit to the toilet.

“Time for us to go pick up Malee,” said Dtui. She stood to leave. “She’s with a neighbor and they’ll want to get to bed.”

Despite his lofty position, Chief Inspector Phosy and his wife were still billeted at the police dormitory until their modest government house was completed. To his wife’s mixed disappointment and admiration, he’d refused to move into the palatial two-story abode of his predecessor.

“Come husband,” she said.

“I’m fine to drive the Vespa,” said Phosy.

Dtui twiddled her fingers and he handed her the key. She knew that if he felt the need to tell her he was fine there had to be some doubt. Even in the carless streets of the capital there were potholes and sleeping dogs, and her husband had worked thirteen hours that day. He’d be safer on the pillion seat. They’d started toward the street when Siri remembered his letter.

“Oh, wait,” he said, and pulled the folded paper from his top pocket. “A quick translation and you can be on your way.”

He explained how the note had been attached to Ugly’s tail sometime that morning. Nurse Dtui, hoping for a study placement in America, had put in many hours to learn English. In’75, armed with a scholarship and high hopes, she’d watched the Americans flee, and, like their Hmong allies, Dtui was stranded. She looked up from the words with an expression of horror on her face. Her English was competent enough to read Siri’s letter and good enough for her to realize the menace it contained. She called Phosy back from the street and had the team sit once more around the table beneath the buzzing fluorescent lamp while she translated. Siri and Daeng appeared to be unmoved by the content.

“You don’t seem that concerned,” Phosy told them.

“It wouldn’t be the first threat we’ve received,” said Siri. “Almost a weekly event,” said Civilai.

“Well, I’m your friendly local policeman,” said the chief inspector, “and I’m not going to let you laugh this one off. It isn’t just a threat to you, Siri. The writer is promising to hurt your loved ones and that includes everyone at this table.”

“I don’t love him,” said Civilai. “I’m not even that fond of him. That should let me off the hook.”

“Ignore him,” said Daeng. “He’s having one of his difficult years. Go ahead Phosy. What do you suggest?”

“First, I suggest we look at the letter for what it does, not just for what it says.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” said Civilai.

“Well,” said Phosy, “the fact that it’s in English sends a message in itself. As Siri doesn’t speak the language I doubt he’s antagonized too many English speakers in his life. And, even if the writer knows more than one language, why would he choose English for this particular threat?”

“I’m assuming you’ll just be asking a batch of questions and have us fill in the answers later,” said Civilai.

“I think that’s a splendid system,” said Madam Daeng. “Continue, Phosy.”

“Secondly,” said Phosy, “why does he only have two weeks to complete his mission? If he lived here there’d be no restriction.”

“So, he’s a visitor,” said Nurse Dtui.

“On a visa,” said Siri. “We aren’t that generous in the immigration field.”

“And we just left a room full of foreign journalists who are in town for exactly two weeks with nice fresh correspondent visas in their passports,” said Phosy. “Any one of them could be our writer. Even the Eastern bloc boys would have a grounding in English.”

“We can’t interrogate all sixty-four of them,” said Daeng. “We need to eliminate some.”

“Well, he’s certainly not Vietnamese,” said Dtui. “How do you know?” Siri asked.

“He gave Ugly a break,” she said. “They still eat dogs over there. No Vietnamese is going to balk at slicing up a flea bitten mongrel if it serves a purpose.”

They heard a low howl from the street. It might have been a coincidence but Siri doubted that.

“Okay, there are four Vietnamese journalists,” said Daeng. “That takes us to sixty.”

“Not much of a help,” said Civilai.

“We need to start with the threat itself,” said Phosy. “Siri, the writer made a promise that he would have his revenge. That his lust for vengeance is still burning inside him. I’m guessing that when he made that threat initially you would have sensed that it was more than just words. You would have seen him as capable of following through with it. It would have frightened you. For some time you would have been looking over your shoulder. On how many occasions have you experienced that type of fear in your life?”

All eyes turned to Siri. He looked up at the lamp and seemed to be fast-rewinding through his seventy-six years. He sniffed when he reached the end.

“Twice,” he said.

“Then, that’s—” Phosy began.

“Better make it three times,” said Siri. “Just to be sure. Three times when I truly believed the nasty bastard meant what he said and had the resources to keep his promise. I’m not given to panic, but I confess to missing a few heart- beats on those occasions.”

“Then that’s where we start,” said Phosy. “Who’s first?”

Hooked yet? Get The Second Biggest Nothing delivered right to your door!

Your local bookstore | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Apple Books | Soho Press bookstore