In the spring of 1948, work began on a development of homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, on ninety-seven acres of forest in northern Westchester County bordered on two sides by Kensico Lake, and on a third by the vast properties of a former state senator named Seabury Mastick. It was a community of homes that would come to be known as Usonian, a word Wright mistakenly attributed to Samuel Butler’s novel Erehwon, where it does not appear, but which Wright claimed Butler had coined to distinguish citizens of the United States from other inhabitants of the Americas. Wright believed this was the future of the American homestead, these small, mostly one-story houses built on concrete slabs, each on a circular plot of about an acre set amid rocky knolls and rolling hills covered by sugar maple and yellow beech.

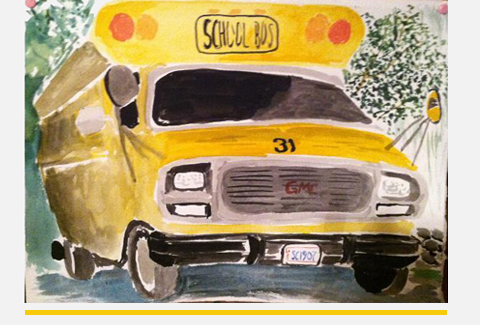

About fifty years later I was hired by a day camp to drive a short yellow school bus along Usonia Road and its environs, picking up campers and ferrying them to the campus in White Plains, and then back home safely at the end of the day. It was a dead end job that involved driving down a number of actual dead ends, and I could hardly have been happier.

The bus, which had an oversized button to turn on flashing red and yellow lights above the windshield and a lever to make a stop sign pop out from the side, was a delight. Its pug nose gently probing the serpentine roads, I watched the sights unfurl: mailboxes and driveways and crooked streams, saplings and stone outcroppings, wintergreen, shot bush, and wood sorrel sprouting from roadside ditches. I would pull into a driveway, open the accordion door and shift to park; the kids would climb on and I’d tell them to put on their seatbelts. Then back on the road, such as it was. One pair of siblings always brought along a small radio shaped like a football, with a CD soundtrack to The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

I’m conscientious enough, but images slip right out of my head. So driving the same roads twice a day was a constant revelation. The homes, built of stone, cypress, cement and glass, were nestled into the landscape and not easily visible. I’d catch a glimpse of a roof on the far side of a hillock, or a carport sticking out from a stand of white ash. It gave the built environment the same fleeting quality as the deer and squirrels that sometimes dashed across the road. The kids would sing along to their disc, changing the lyrics of Peaches & Herb’s “Shake Your Groove Thing” to “Shake Your Booty,” and lose it, giggling.

To make sure I wasn’t late, each morning I headed out early, got a cup of coffee from a gas station, then parked the bus by the edge of a meadow until it was time to make my first stop. I’d roll down the window and wait. A syrupy light fell on the tall summer grasses and the stink of rubber and diesel drifted on the rising heat. I sipped coffee and listened to the buzzing insects, waiting for the morning to click into place. And like a Victorian heroine who pauses at the threshold and does not enter until she is announced, or a story that arrives only when all the words are in place, the day waited, and waited, and then with a rush, began. That’s one reason I tend not to worry too much. No one tells you that it’s only the not-writing that hurts; writing itself is easy as pie.

* * *

* Ed. note: This is an occasional series featuring essays about the various jobs, some good, some not as good, that writers have held over the years. Would you like to contribute? Email us.