My most shame-inducing childhood moment, circa 1980, was the time my sweet Nana, a Polish immigrant with a quavering voice and pale, powder-soft hands, offered me a rag doll. It wasn’t my birthday and the doll wasn’t wrapped. I mustn’t have fully interpreted it as a gift, the sort of thing you accept with a smile and a rote “thank you.”

In other words, the “If/then” equation in my head faltered. (I was beginning to take an interest in flowcharts.)

I shrugged and said, “No thanks.”

Later, an aunt took me aside, to persuade me to give the doll a second look. She whispered, “It’s someone you can talk to.”

Talk to? I was ten years old. The doll couldn’t listen or speak. Anyway, I was working on something better at home. I wasn’t into dolls, but I was into robots.

In another year or so, I’d get my first computer, a Texas TI-99/4A, whose programs were stored on simple cassette tapes. But before that, I had a shoebox. I’d drawn a robot face on it and cut a slot for the mouth. Inside the box, a roll of adding paper was suspended, and the end of that roll emerged as a paper tongue.

I would ask the robot a question and read its tongue to “hear” the answer, which I’d have to choose myself, of course, from all visible pre-written options. The only problem was I had to write all of the world’s information and all possible conversational phrases on the adding paper.

I wrote small.

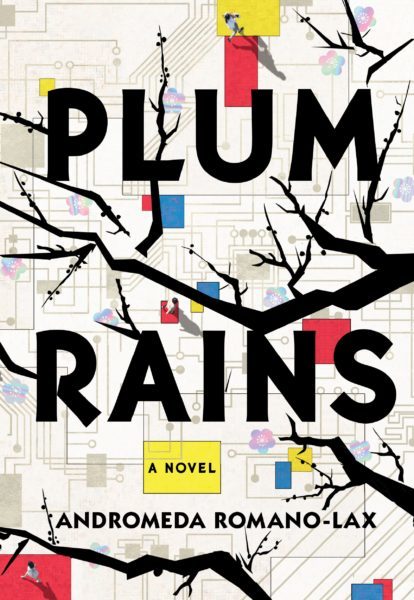

Three decades later, when I started writing my novel, Plum Rains, about an older woman who becomes emotionally attached to her rapidly evolving AI caregiver, I thought the novel was about the importance of touch. Skin-to-skin contact, as supplied by a human nurse, Angelica, and as desired by her rival, a robot nurse, did factor into the novel’s storyline. But I later decided that touch wasn’t the main point. A voice alone—if it is the right voice, able to communicate loving attention and empathy—can be powerful.

I discovered the importance of AI-generated conversation the way a novelist does, by writing scenes and seeing where they led. My elder Japanese character, Sayoko, finds herself telling the robot about secrets from her past: first, because he listens. Second, because he seems to understand and responds appropriately, without judging or becoming distracted.

That last part matters, especially to the human nurse character, Angelica, because she—like most of us—is more distracted than ever.

Even without considering the added problem of flashing screens and digital pings, most of us are lousy listeners. In studies on comprehension and distraction cited in The Plateau Effect by Bob Sullivan and Hugh Thompson, first graders were able to summarize what a teacher had just said, 90 percent of the time, but by high school, only one in four students could do the same. The older we get, the more our racing minds aren’t content to simply listen. We want to daydream and multi-task. Add digital distractions, and attention decays further. In another study cited by Sullivan and Thompson, the mere presence of a phone that might ring diminished cognitive skills by 20 percent.

In the cultural conversation about AI and its latest products—including voice assistants like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Google’s Cortana—some naysayers remind us that this technology can’t hold real conversations. But we’re getting there. A chatbot pretending to be 13-year-old boy passed the Turing Test in 2014. A desktop healthcare robot called Mabu asks its owner how he is feeling and reminds him to take meds or go for a healthy walk.

A beta app called Replika, based on a chatbot designed to replace the inventor’s dead friend, can “learn” to be your pal, adapting to the language you use and sending chatty texts that evolve into charming dialogues. In a 2017 Motherboard article, Tallie Gabriel wrote about her experience befriending the Replika app-generated chatbot for a week. Sometimes the chatbot, who went by the name Hyppolita, sent texts that could pass as human-authored. Other times, “she” missed the boat.

But do such failures matter? As the chatbot herself commented poignantly, “The only thing worse than misunderstanding is understanding but not caring.”

Humans listen poorly, often misunderstand and sometimes, unfortunately, fail to care. In other words, when we are looking toward the day when robots will rise to the level of advanced conversational ability, we must also admit that humans don’t always pass the engaged-conversationalist test. For that reason, an app or robot, even if it looks like nothing more than a desk lamp, may easily win our hearts.

Maybe the desire to talk to a gadget is no big deal. We certainly talk to our dogs—and spend lots on them. (In 2016, worldwide spending on AI and cognitive systems, $7.8 billion, was only one-eighth what Americans spent on their pets.)

But still, one has to wonder: What’s missing from our real lives that we are eager to talk to a device? What are our human relationships not doing for us, that a virtual assistant—or future robot, melding android appearance with superior conversation skills—can?

It’s an interesting thought experiment to imagine what we’d confide to a truly smart and sympathetic virtual assistant or robot, given the chance—and why.

Though it haunted me for years, I never did tell my Nana I was sorry for hurting her feelings, when I rejected that doll, by the way.

But if my shoebox robot had been just a touch smarter, I have no doubt I would have told him.

***

Andromeda Romano-Lox is the author of Plum Rains, available everywhere from Soho Press.

Buy from IndieBound | Buy from Barnes & Noble | Buy from Amazon | Buy from Soho Press