The problem with setting fiction in the near future is that it keeps coming closer—and usually about twice as fast as one expects. By mid-century, will we still stare at our phones? Or will we instead use bionic contacts (already in development, mind you) that project images of our incoming texts?

Will we even call those brief messages “texts”?

Speculative fiction pioneer William Gibson likes to inform interviewers that the true point of sci-fi is not to predict the future. His classic Neuromancer, written in 1984 and set in about 2035, failed to predict mobile phones, as did the movie Blade Runner, in which clunky, stationary videophones predominate.

And yet: one doesn’t want to create a world that will become obsolete only years after a book appears. Worse yet, one doesn’t want to include details that are passé even prior to publication. In our fast-moving world—Amazon’s Alexa made her debut in late 2014 and starred in a Super Bowl ad that counted on pop-culture familiarity only three years later—the chances of getting the near-future wrong are greater than ever. Yet more and more novelists, intent on penning semi-realistic sci-fi hybrids, seem to be taking the chance.

When I first started imagining Plum Rains, a novel set in 2049 about a much older woman and the robot delivered to care for her, threatening the livelihood of an immigrant nurse with her own problems and secrets, the world was a different place. The iPhone was a year old. I wasn’t even using a dumbphone yet. iPads, Fitbits, and voice assistants like Siri weren’t on the market. I’d never downloaded an app, making me an unlikely novelist to guess what the world might look like a few years hence. Just the fact that I’d use a word like “hence” probably undermines my reputation as an aspiring futurist.

Yet when I first started imagining the book, some aspects of the future were already well established. In 2007, South Korea had announced the need for an ethical charter for robots—not only to protect humans from AI, an old trope, but to protect vulnerable future androids from people as well. Many years ahead of movies like Her (2014) or Ex Machina (2015), that news item planted a seed.

Also in 2007, author David Levy published Love and Sex with Robots, predicting that human-robot marriages could be expected by 2050. He has since gone further, claiming that robots and humans will be able to make offspring, based on recent advances in bionanotechnology.

These early rumblings set the stage for the questions my novel raises and which our factual future will pose: do we really want social robots advanced enough to replace human relationships? To what extent should we automate the care of elders, children, and other vulnerable members of society? Should we not only be afraid of robots who will make war, but also of robots who will make love?

These are the types of questions that sci-fi has always asked, but only recently have they ceased being wild speculations. They’re the stuff of science journals, public debates, ethics campaigns and realistic—or nearly realistic—fiction.

I originally pictured my robot story as happening by mid-century. But darn it, things kept speeding up: the same problem, I’d wager, facing many novelists who try to set a plot ten or twenty years from now.

I had to bring my own story twenty years closer, re-jiggering it for the year 2029. And still, it seemed that the future would keep speeding toward me faster than was convenient, shrinking the gap between the impossible-to-pin-down “now” and the “coming soon” future I wanted to depict.

Between the first conception of Plum Rains and its final execution, I wrote two other novels. By the time I got a few chapters on paper, robot eldercare wasn’t a prediction, it was an evolving reality. The harp seal-shaped PARO Therapeutic Robot, often used with dementia patients, was first exhibited in 2001; in the U.S., it’s been around since 2009.

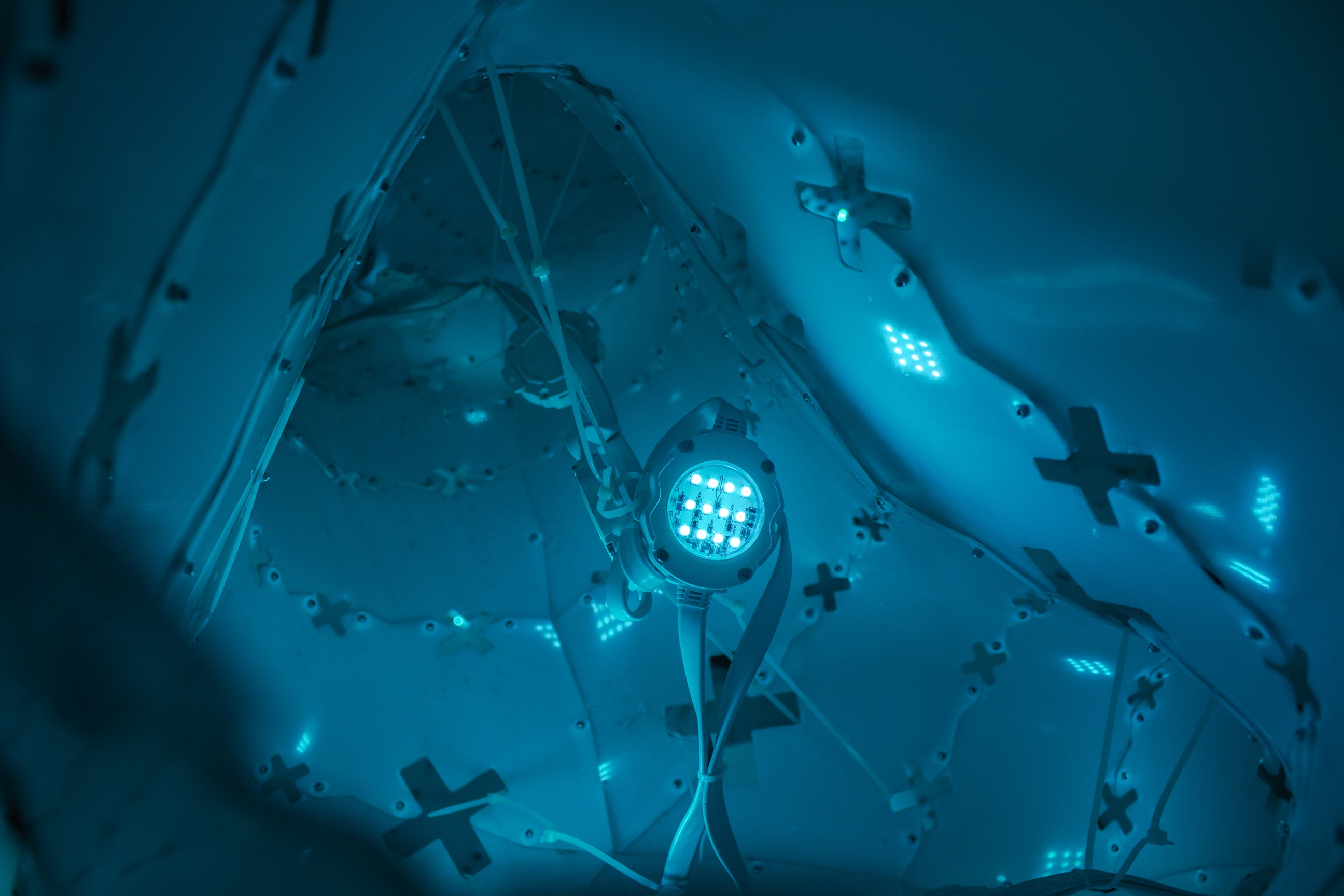

Robots are being developed to lift clients and administer medication. A new eldercare desktop robot called ElliQ entered beta testing in January, joining the already launched healthcare companion called Mabu. These first-wave robots read aloud emails, remind their owners to take medication or get some exercise. They’re helpful devices, of limited but still impressive intelligence. They aren’t fully ambulatory, socially sophisticated, medically expert human replacements, in other words.

But the market for more advanced social robots—especially ones designed to help the elderly—is huge. Awaiting my own pub day, I had to gamble that my eldercare robot scenario for 2029 wouldn’t seem hopelessly quaint by 2019.

Of course, my book isn’t really about gadgets or predictions. It’s about immigration, labor, the environment, and complicated ethnic identities.

Most fundamentally, it’s about relationships: about secrets kept and revealed, connections lost and made.

Where my own novel does aim to be a crystal ball, the forecast offered is less about what kind of robot could hit the market in 2029 than why we will need such a robot at all, as well as what consequences may ensue. The setup is less about tomorrow than about today, as has always been the case with books about the supposed future. As William Gibson once noted, Orwell’s 1984 is really about 1948.

If my future fiction is really a lens for seeing the present, as is my historical fiction, why not just set it in the present, then? Because if the near future is hard to see, the present is even harder. It’s the water all around us, including features we might be resistant to acknowledging.

Defamiliarization, achieved by setting a plot in a different time or place, can help us suspend judgments and shift us onto new tracks of perception, for reasons that can be explained via the psychology of Daniel Kahneman, the literary theory of Viktor Shklovsky, or by simple poetry.

As Emily Dickinson wrote, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant—/Success in circuit lies.”

Not “success in circuit boards,” necessarily. But I’d like to think the poet would understand. She also wrote:

“The Future—never spoke—

Nor will He—like the Dumb—

Reveal by sign—a syllable

Of His Profound To Come—”.

***

“In this profoundly inquisitive and compelling novel, Romano-Lax sets timeless human dilemmas involving love, racism, misogyny, violence, grief, and dissent against environmental decimation, the daunting ethical questions raised by burgeoning AI, and consideration of the very future of humanity.”

–Booklist, Starred Review

Buy from IndieBound | Buy from Barnes & Noble | Buy from Amazon | Buy from Soho Press