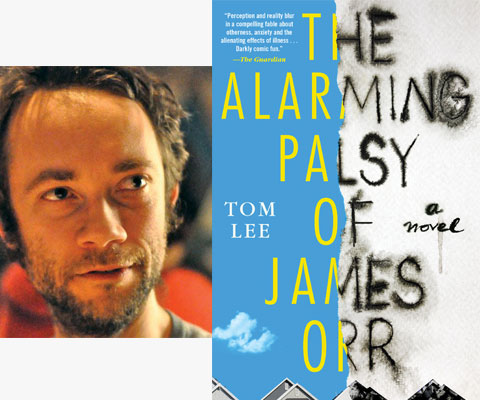

Today we celebrate the publication of Tom Lee’s extraordinary novel, The Alarming Palsy of James Orr.

A Kafkaesque and darkly humorous “suburban gothic” tale that tracks the unraveling of man’s body, mind, and life, it is told in “clipped, cold-blooded sentences [that] form a thin mantle over the sinisterly simmering plot of a mesmerizing first novel.”

Read Chapter 1 below.

More about the book:

James Orr—husband, father, reliable employee and all-around model citizen—awakes one morning to find half his face paralyzed.

Waiting for the affliction to pass, he stops going to work and wanders his idyllic estate, with its woodland, uniform streets and perfectly manicured lawns. But there are cracks in the veneer. And as his orderly existence begins to unravel, it appears that James himself may not be the man he thought he was.

A deeply unsettling story of creeping horror that consistently confounds expectations, The Alarming Palsy of James Orr introduces a writer of extraordinary and disturbing talents.

“Astonishing and riveting . . . a perfectly calibrated absurdist novel that amuses and unnerves in equal measure.” –Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

~

Chapter 1

When James Orr woke up, a little later than usual, he had the sense that there was something not quite right, some indefinable shift in the normal order of things, but it was not until he bumped into his wife on the landing—James had been sleeping in the spare room for several weeks—that he had a clue as to what it might be.

“Oh!” said Sarah Orr, and put her hand to her mouth in genuine alarm.

James continued to the bathroom and there, in the mirror, he saw the cause of her dismay—and such dismay did not seem unreasonable.

The left-hand side of James’s face had collapsed, a balloon with the air gone out of it, a melted wax-work. The cheek was hollow and the skin hung in a bulge over the side of his jaw, a grotesque one-sided jowl. The side of his mouth had fallen, too, the pale line of his lips angling sharply downwards. Where the bottom of the eyelid had pulled down, the full white of the eye was exposed, as well as its veiny roots. The skin itself was different. Yellowed, blood- less, and a little shiny.

James tried to smile. Only the right-hand side responded. The right eye narrowed, the skin creased into folds, the corner of the mouth hoisted itself upward and pulled his lips back over his teeth. The left side remained slumped, unmoved. The effect, a forced and crooked grin, the teeth bared on one side, was appalling.

Sarah stood next to him, staring at his reflection in the mirror.

“My god, James, what is it? Have you had a stroke?” She laughed, nervously. “I’m sorry—you just look so . . . awful.”

James turned on the tap, splashed his face with water and then looked again. He put his hand to his face and it was like touching someone else. He pushed the left side up so that it was level with the right but it was not convincing, and when he let go, it dropped slackly back down.

“It won’t move,” said James. The words came out thickly, caught in his half-closed mouth. “It’s paralysed.”

And yet it was not simply this, the sight of the paralysed features themselves, that was so unsettling, it was the discord between right and left. If both sides hung like this, then perhaps, at least when his face was at rest, he would only resemble a much older man—himself thirty or forty years from now. As it was, it gave the impression of two different faces, two different people, welded savagely together.

“Don’t come downstairs,” said Sarah. She had recovered herself. James recognised the tone—practical, coping, in charge—most often employed when there was some kind of drama involving the children, a sound that he usually found reassuring. “I’m going to sort out the kids.”

“Okay,” murmured James, out of the side of his mouth.

He turned back to the mirror. The only thing on the left-hand side of his face that moved was his eye. But when he blinked, only the right eye closed. The left stared unrelentingly back at him. Its gaze seemed agitated, intense, almost accusatory, as if all the expressiveness of that immobilised side of his

face was now concentrated there. From downstairs, he heard the everyday noises of his wife and children having breakfast, getting ready to go out, sounds that suddenly seemed full of pathos, or at least a kind of anticipated pathos. The eye had a yellow, filmy look to it, almost as if it were sheathed in something else. The edges of the cornea were reddening. It felt dry and was already a little sore.

~

Amazon | Barnes and Noble | Apple | IndieBound | Soho Press