Rituals, Riches, and Superstition

Kwei Quartey discusses the real-life internet scam culture behind the first book in his latest crime series.

Many people are familiar with those Nigerian “419” emails in which the sender claims he is an African prince on the verge of inheriting millions, which he will happily share if you could simply send him $5000. But now, 419 has evolved into much more sophisticated schemes like credit card fraud, gold scams, Iraq war vet scams, and others. The rewards here are higher because the swindles are often more credible than the original 419. In Ghana, West Africa, Ghanaian fraud boys, also called “sakawa boys,” have proven themselves expert con artists—perhaps even excelling beyond their Nigerian counterparts.

“Saka” is a word from the Hausa language that means “to put in,” referring to the act of placing items in the virtual shopping cart on sites like Amazon. Originally, “sakawa” referred only to the act of duping people of their money through online scams. The victims were and still are largely Americans and Europeans.

While the jackpots for successful sakawa boys grew larger over the years, the work became more complex and competition stiffened considerably. So, looking for ways to make more and more money, sakawa boys turned to superstition. As in other African countries, belief in the supernatural is widespread and strongly held in Ghana. It’s no surprise, then, that it ultimately gained access to the sakawa world. These sakawa swindlers now use third parties such as traditional priests, considered intermediaries between the physical and spirit worlds, to gain ever greater deceptive powers through the blessings of the gods. It’s in this sense that the word sakawa has come to signify Internet fraud plus the supernatural.

But it’s not as simple as it may appear. The fetish or traditional priest often demands from his fraud-boy clients near-impossible and sometimes gruesome tasks like procuring body parts such as human lips or genitalia, which are of great value in rituals.

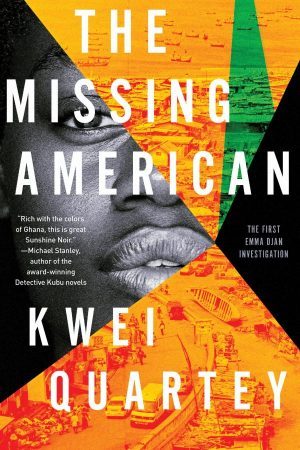

Sakawa shapes much of my latest novel, The Missing American. What makes the phenomenon so absorbing is that it incorporates age-old superstitions with the modern technologies of computers, mobile phones, and even real-time facial reenactment software. The two disparate realms are not a zero-sum game: it’s not that technologically savvy people have no superstitions, nor that superstitious people can’t possibly use advanced technology.

Internet fraud is of course a crime, and buried within it in turn are well-known motives for murder: greed, lust, power, and so on. Unsurprisingly, just as drug-dealing doesn’t remain confined to drug dealers, neither is sakawa solely the province of sakawa boys. There’s too much money to be made, and so the business reaches up into upper echelons already primed by corruption in other areas. Thus, The Missing American exposes a shockingly widespread network in which murder is the inevitable consequence. For Emma Djan, the rookie private investigator who is pulled into the case, it is a baptism by fire.

by Kwei Quartey

Read Kwei’s Op-Ed about the slaying of Ghanaian journalist Ahmed Hussein-Suale, The Jamal Khashoggi of Ghana, in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

Kwei Quartey was born in Ghana and raised by a black American mother and a Ghanaian father. A retired physician, he writes full-time in Pasadena. He is the author of five other critically acclaimed novels in the Darko Dawson series, Wife of the Gods, Children of the Street, Murder at Cape Three Points, Gold of Our Fathers and Death by His Grace. Find him on Instagram @crimefictionwithkweiquartey and on his website, kweiquartey.com.