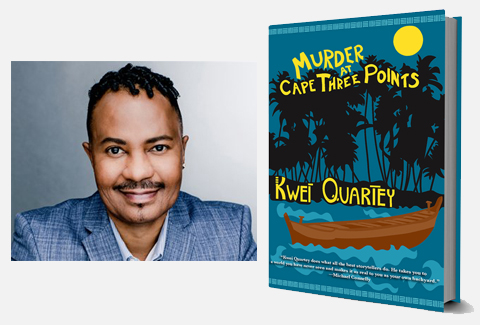

Kwei Quartey was born in Ghana and raised by a black American mother and a Ghanaian father, both of whom were university lecturers. As a teenager, he got into serious trouble with the military government for putting up protest posters; after a stint in prison for “sedition,” he left for the United States, where he has lived ever since. In 2008 he returned to Ghana for the first time, and now visits frequently as research for his writing. A practicing physician, he now lives and works in Pasadena. He writes in the morning before he sets off to work at HealthCare Partners, where he runs a wound clinic. He is the author of Murder at Cape Three Points, the third novel in the critically-acclaimed Darko Dawson series.

How do you pronounce your name?

It’s pronounced, “Kway Quart-ay.” It is a Ghanaian name. The full version is Jones-Quartey.

Your father was Ghanaian. And your mother?

She’s black American. She met my father while she was at Hunter College in New York, where he was studying Political Science at Columbia University. They got married and my mother went with my father back to Ghana.

So, you were born in Ghana?

Yes, all three of my brothers and I were born in Accra, the capital.

Did you live in the city?

Both my parents were university lecturers, and we lived on the campus of the University of Ghana on the outskirts of the city.

Did you have the opportunity to visit the States when you were growing up?

The extra perk the university granted my mother in her official status as an “expatriate” was a fully paid trip to the States for her and her children every two years. So we spent many happy summers in New York. Travel was easy because, born to an American mother, my brothers and I were U.S. citizens by the regulations at the time.

Do you think the university environment as you grew up had a lot to do with your interest in writing?

Undoubtedly. Our house was a treasure trove of books. There were hundreds of books, both fiction and non-fiction, in all our bedrooms, the sitting room and the study—even the dining room. On Saturday mornings I liked to go down to the university bookshop, which was very well stocked, and spend hours browsing. Yes, I was your classic nerdy kid reading on a Saturday instead of out playing soccer. Reading as voraciously as I did inspired me to write my own “novels” when I was around eight to ten years old. I typed or hand-wrote them, and then stapled them together and bound them with illustrated cardboard covers.

What influence did your parents have on your writing?

They had a huge influence. My mother nurtured my creative instincts, and my father showed me the craft of writing. He was a writer of non-fiction, and I remember the tap-tap-tap of the typewriter keys as he worked late into the night. His demonstration of tenacious dedication to writing inspired me tremendously.

Why did you leave Ghana?

It was a combination of things. First, my father died of pancreatic cancer. My widowed mother was without relatives of her own in Ghana, and she began to feel like returning to New York City, where her own mother lived. Secondly, the then military government of Ghana had put the country in an abysmal state of financial ruin. There was university student unrest, and our schooling kept getting interrupted.

After a long absence, you went back to Ghana in February 2008. What was that like?

Almost surreal. I didn’t recognize a lot of places because of the amount of development that had taken place in my absence. There were skyscrapers going up, brand new American-style malls and supermarkets, restaurants of all types, pizza parlors—I was dumbfounded. Ghana’s economy at the time was said to be growing at 8%, and with the new oil discovery, it’s now around twice that much. No matter how impressive the growth rate figures in Ghana, though, for the majority of citizens, it’s not all sweetness and light. Like most developing countries, the financial sector can surge while poverty remains rampant on the city streets and in the rural areas.

Would you like to give up practicing medicine in order to write full time?

I can see myself happily writing all day long without spending another minute in medical practice, but the fact is that practicing medicine keeps my soul open to those sensibilities important to creativity. And the reverse is true too—writing as I do very early in the morning gets me mentally prepared for the day of practice in clinic. So the two careers, medicine and writing, are symbiotic.

Much of the practice of medicine is like writing a mystery. The whodunit and howdunit in the story is exactly like trying to detect what ails a person. In fact the doctor is the detective, whether he immediately announces, “Aha, I know what’s wrong,” like Sherlock Holmes saying, “Elementary, my dear Watson,” or he has to assemble a bunch of clues before he feels confident to make the diagnosis. And of course, the diagnosis is the triumphant denouement.

* * *

About Murder at Cape Three Points

At Cape Three Points on the beautiful Ghanaian coast, a canoe washes up at an oil rig site. The two bodies in the canoe—who turn out to be a prominent, wealthy, middle-aged married couple—have obviously been murdered; the way Mr. Smith-Aidoo has been gruesomely decapitated suggests the killer was trying to send a specific message—but what, and to whom, is a mystery. The Smith-Aidoos, pillars in their community, are mourned by everyone, but especially by their niece Sapphire, a successful pediatric surgeon in Ghana’s capital, Accra. She is not happy that months have passed since the murder and the rural police have made no headway. READ MORE …