Juliet Grames: One of the main characters in Death of a Nightingale is a Ukrainian woman named Natasha. We meet her in a prison convoy: she has been convicted of the attempted murder of her ex-fiancé and thrown into Danish prison. How did you dream up Natasha’s character and storyline?

Lene & Agnete: Natasha has been part of the Nina Borg storyline ever since The Boy in the Suitcase. At first she was just a young woman so terrified of being deported that she would put up with just about anything—including an abusive fiancé—to be allowed to stay in Denmark. It was only gradually that we began to wonder why she was so terrified. She developed from being a peripheral character, mainly defined by her role as a victim, into something much more complex. Had she been from Poland or Slovakia or pretty much any other East European nation, her deportation would have been immediate and automatic, since the Danish authorities regard those countries as “safe”—that is, territories where rejected asylum-seekers will not be met with persecution. This would not suit our purposes; we needed her to stay around for three whole novels, so she had to be from Ukraine, one of the very few former East-bloc countries still considered so questionable from a human rights point of view that deportation cannot be automatic. As a matter of fact, you could say that not only Natasha’s nationality but most of the plot of Death of a Nightingale was decided by Danish foreign policy…

Juliet: Part of the book is set in the 1930s in a Ukrainian village that has been damaged by a recent famine. How did you decide on this plotline and setting? How did you research it and make it feel so realistic?

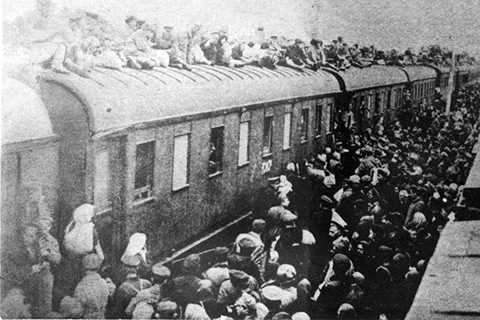

Lene & Agnete: The Holodomor—the great famine caused by Stalin’s drive to force Ukraine’s farmers into collectivization—came up when we started researching the history of Ukraine. We were both amazed that a disaster of that magnitude could have escaped our notice; numbers are uncertain and fiercely debated, but several million people lost their lives, and yet we had never heard of it. We decided to dig a little deeper and were lucky enough to find quite a few first-hand accounts. But books and pictures can take you only so far. Luckily, Ukraine has an excellent open-air museum at Pirohiv, not too far from Kiev, where we could walk among houses like the ones that would have made up Olga’s village, and visit a school room like the one in which she and her sister Oxana would have been taught.

Juliet: At the core of the plot of Death of a Nightingale is a secret from the distant past—seventy years ago—that is still having an effect on contemporary Ukrainian politics. Was this motif a fictional invention for the book? Or in your research did you encounter real incidents where Soviet-era scandals are still treated this seriously?

Lene & Agnete: Oh, the past is very far from dead in Ukraine. In current affairs, it matters what you grandmother did and whose side your father was on. In the 2004 presidential campaign, the pro-Russian Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovytch called the Nationalist candidate Viktor Yushchenko “a Nazi,” and Yushchenko’s wartime pedigree came into play—how his father had been imprisoned at Auschwitz as a Red Army Soldier, how his mother had hidden some Jewish girls at great risk to herself. Then, when Yushchenko became president, he made Holodomor-denial a criminal offense. However, Yanukovytch was eventually re-elected and went on record saying that the Holodomor could not be called genocide but was “a common tragedy of the Sovjet people.” Yushchenko made Ukrainian nationalist and anti-sovjet army leader Stepan Bandera a posthumous “Hero of Ukraine”—Yanukovytch annulled that honor. Soccer fans from Lviv in Western Ukraine regularly fly a huge banner with Bandera’s face on it, particularly provocative when they are playing a team from the more pro-Russian areas in the east. Ukraine is far from ready to let Stalin era events be relegated to the cold case files.

Juliet: How did you collaborate on the actual writing of this book? Did one of you write certain characters’ points of views? Or did you share them all?

Lene & Agnete: The collaboration mostly works because of intense preparations. Before we really start writing, we have mapped out the story and the plot, scene by scene, so that we can basically dip into it at any point—Agnete may be busy writing Chapter Six, while Lene is deep into Chapter Sixteen, it doesn’t really matter. We gossip about the characters as if they were real people, we share pictures, research files, quotations—and, of course, impressions from the research trips. All so that we can work from a common base. We’ve sworn a bloody oath never to reveal exactly who wrote what . . . and actually, we both make it a point to write a bit in the voice of even those point-of-view characters for which we are not primarily responsible—it helps you understand them better, and it means that we are better equipped to critique and edit each other’s work.

Juliet: In Death of a Nightingale, we finally learn more about a dark secret from Nina Borg’s past—one that has been alluded to in previous books but never spelled out. Can we hope to learn more about this chilling episode in a future Nina Borg book?

Lene & Agnete: Actually, in the fourth novel—we’ve just finished the draft—calamity in the shape of an attempted murder finds Nina in the town where she grew up. She is supposed to be helping her mother through a time of serious illness, but ends up being in dire need of help herself. And yes, the ghosts of the past do close in . . .

* * *

Lene Kaaberbøl and Agnete Friis are the Danish duo behind the Nina Borg series. Friis is a journalist by training, while Kaaberbøl has been a professional writer since the age of 15, with more than 2 million books sold worldwide. Their first collaboration, The Boy in the Suitcase, was a New York Times and USA Today bestseller, and has been translated into more than 30 languages.