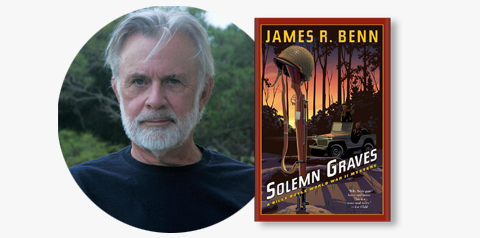

Solemn Graves, the thirteenth book in the Billy Boyle series by Soho Crime author James R. Benn publishes in September, and we could not be more excited.

It seems each of these books is somehow better than the last, and Benn’s unique ability to weave together a fast-paced plot and a deep-dive into WWII history is nothing short of thrilling.

In fact, Publishers Weekly just issued the book a starred review, saying: “Exceptional … Benn has never been better at integrating a whodunit plot line with a realistic depiction of life on or near the battlefield.”

To tide you over until the book’s release, we thought you’d like to read an excerpt.

The first chapter is below.

ABOUT THE BOOK

US Army detective Billy Boyle is called to investigate a mysterious murder in a Normandy farmhouse that threatens Allied operations.

July, 1944, a full month after D-Day. Billy, Kaz, and Big Mike are assigned to investigate a murder close to the front lines in Normandy. An American officer has been found dead in a manor house serving as an advance headquarters outside the town of Trévières. Major Jerome was far from his own unit, arrived unexpectedly, and was murdered in the dark of night.

The investigation is shrouded in secrecy, due to the highly confidential nature of the American unit headquartered at the Manoir de Castilly: the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, aka, The Ghost Army. This vague name covers a thousand-man unit with a unique mission within the US Army: to impersonate other US Army units by creating deceptions using radio traffic, dummy inflatable vehicles, and sound effects, causing the enemy to think they are facing large formations. Not even the units adjacent to their positions know what they are doing. But there are German spies and informants everywhere, and Billy must tread carefully, unmasking the murder while safeguarding the secret of the Ghost army—a secret which, if discovered, could turn the tide of war decisively against the Allies.

EXCERPT

July 1944

NORMANDY, FRANCE

~

Chapter 1

The first dead body I saw in Normandy was a cow, tangled in the branches of a shattered tree at a crossroads by the edge of a field, a good thirty feet off the ground. More of them lay scattered across the pasture, the thick green grass dotted with gaping holes of black, smoking earth.

A few cows were still upright. One wandered into the ditch alongside the road, trailing intestines and bellowing, her big brown eyes crazed with fear and pain.

“Stop,” Sergeant Allan Fair said from the front seat, placing a hand on the driver’s arm. “Easy like.” The driver, a skinny kid who looked like he might shave soon, if he lived that long, let the jeep roll to a halt. Fair got out, planted his feet, raised his M-1 to his shoulder, and squeezed off a round that found a home between those two brown eyes. The cow collapsed into the ditch, and silence filled the air.

“Damn,” Fair said to no one in particular, and got back in the jeep. The driver eased into first gear and took off slowly, carefully navigating around a shell hole on one side of the hard-packed dirt road. We passed a sign at the crossroads, tilted lazily to one side and peppered with shrapnel.

Dust means death.

As we drove on, the roadside was decorated with the burned-out hulks of vehicles whose drivers had not heeded the warning. The bovine casualties had likely been the result of a nervous driver who barreled down the road, kicking up a dust storm and making it through before the German shells rained down on the intersection.

“I didn’t think we were close to the front yet,” I said from the back seat, as we proceeded at a dust-free twenty miles an hour under the hot morning sun. “I mean, for Kraut artillery spotters.”

“It’s close enough. They’re up in those hills,” Fair said, sweeping a hand toward the distant rise to the south. “With a good pair of binoculars, they can pick out a swirl of dust five, ten miles away. Plus, they left spotters behind, hiding out in barns or in the woods.”

“Scuttlebutt is, they pay the French for any dope they bring them about targets,” the driver said.

“Hard to imagine any Frenchman would sell information to the Germans,” Big Mike said.

“How long you been in Normandy?” Fair asked.

“We got here yesterday,” Big Mike said.

“Figures,” was all Fair said.

“We seen pictures,” Big Mike said. “People throwing flowers at GIs, stuff like that.”

“Anyone throw flowers at you, kid?” Fair asked the driver.

“A Kraut threw his helmet at me when his rifle jammed,” he said.

“But no flowers.”

“See? So don’t believe everything you read in Stars and Stripes,” Fair said. He spat into the road, ending the conversation.

Big Mike looked at me, eyebrows raised. Or looked down at me, I should say. Big Mike—Staff Sergeant Mike Miecznikowski—was tall and broad and took up most of the cramped back seat.

“I was looking forward to the flowers, Billy,” he said. “In Sicily, all they threw were stones.” The jeep moved slowly, past open fields and into more hedgerows.

Here, the roadway became a narrow, sunken lane with a deep ditch on either side. For centuries, farmers had been mounding earth to mark the boundaries of their fields and to keep livestock in. Topping it all off was a tangle of trees and bushes, their roots intertwined with the gritty gravel, dirt, and stone base.

Hedgerows made every pasture a fortress, every lane a death trap.

“How long have you been here, Sergeant Fair?” I asked. Fair had been ordered to take Big Mike and me from First Army headquarters to the outskirts of Bricqueville, where a dead body was waiting for us. Not the sort that ended up in a tree or torn apart by explosives, but the kind that found itself wearing a slit throat in the sitting room of a French villa, safe behind the lines, and wearing the uniform of a US Army captain. Simply said, it was murder, an almost quaint and old fashioned custom these days. Killed In Action was the usual phrase, and here in hedgerow country—the French call it the bocage—there was a lot of it going around.

“I been on the line since D+3,” Fair said, his voice a low mutter as he turned to study me. He did his best to look unimpressed. My ODs were clean, and from the SHAEF patch on my shoulder, I was obviously nothing but a headquarters feather merchant out for a joyride. Fair was headed back to the front, where he’d been since three days after D-Day. His olive drabs were worn and muddy, bleached by the summer sun to a shade not found in any Quartermaster’s stores. The bags under his eyes were as dark as midnight sin, and crow’s-feet arced from the corner of his eye, an occupational hazard from squinting over the sights of an M1. His mouth was a thin slit of insolence. His eyes were narrowed, wary, and suspicious. He didn’t bother saying “sir,” but I didn’t care about that. At the front, there was an unspoken rank, and it wasn’t based on an officer’s bars or a non-com’s stripes. It had to do with how long a man faced death and kept going despite it. All Fair knew was that Big Mike and I still had the smell of London about us, and that made us nothing but nuisance cargo in his book.

I didn’t blame him one damn bit.

“Anything else, Captain?” Fair said, his eyes scanning the road as it curved ahead. Which was obviously of greater interest to him than any stupid questions a desk jockey from Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force had. Probably why he was still alive.

He clamped a hand on the driver’s arm, signaling him to roll to a dustless halt.

“Look, he’s making a run for it,” Fair said, pointing to a flurry of road dust off to our right, where the land sloped away.

“Who?” Big Mike asked.

“The jerk who got all those cows killed,” the driver said.

“They’re dead meat,” Fair said, leaning back and shaking a Lucky Strike loose from a crumpled pack. He lit one, ignoring the sound of distant booms and the screaming crescendo of shells coming in from the German lines. “The Krauts got a crossroads over there zeroed in.”

Explosions crumped a mile or so away, just ahead of the dust cloud, belching smoke and fire as they ripped through trees and shrubs. Then it was over. Fair drew in his smoke as if it were oxygen, cupping the cigarette even in broad daylight.

“Shouldn’t we see if they need help?” I asked.

“Naw,” Fair said, shaking his head at what to him was obviously a silly question. “Lemme finish my smoke.” He did, tossing the butt into the road as two more shells landed out where smoke from a burning vehicle was already curling into the sky.

“Krauts always send a few in after the fact,” Fair said, signaling the driver to move on. “To pick off guys who don’t know any better.”

Meaning us.

The driver eased his way around the curve, keeping the speed down. Down so much we could have walked and kept pace. But I didn’t complain, since I liked not being blown up.

“They ain’t going to like keeping a stiff around this long,” Big Mike said, meaning our murder victim, who had apparently bled out in the sitting room of a farmhouse.

“There’s stiffs all over the place,” Fair said. “Ours, Krauts, and plenty of French who can’t get out of the way fast enough.”

“Out of the way of what?” Big Mike asked.

“Pissed-off Krauts, our planes bombing and strafing the hell out of everything, artillery, land mines, drunk GIs, you name it,” Fair said. “If I was them, I’d have gone south.”

“I think they like the idea of being liberated,” Big Mike said.

“Yeah, it’s working out just swell for them, isn’t it?” Fair said.

He had a point. Along our section of the line, the bridgehead from the beaches to the front lines was no more than eighteen miles deep, after a month of hard fighting and heavy casualties. It was a killing slog for the GIs, but French civilians were often worse off, caught in a cross fire of bullets, shells, bombs, and brutality. Things weren’t going all that well, truth be told. By now we should have broken out of the bridgehead, our tanks rolling toward Paris. But the Allied armies were still cooped up in Normandy, fighting for every hill and hedgerow and paying a heavy price.

“Look,” our driver said, pointing to the source of the smoke. A supply truck was on its side, burning, the rubber tires sending up thick, acrid smoke. Two bodies were in the road, thrown from the cab when it had been hit.

A couple of Frenchmen knelt by the bodies. They glanced up as we quietly rolled to a halt twenty yards away. One, caught in the act of rifling through the pockets of a dead GI, hastily stuffed a pack of smokes in his jacket. His pal let the arm of the other corpse flop to the ground as he filched a wristwatch.

Both soldiers were shoeless, their boots laced and draped around the necks of the Frenchmen. Farmers, by the rough cut of their worn clothes, although most residents of Normandy looked ill fed and poorly clothed these days.

“Goddammit,” Fair said, stepping out of the jeep and advancing upon the men. I followed, noticing bits of paper scattered in the dirt around the bodies. Photographs and letters, tossed aside as the bodies were looted. The men muttered in rapid-fire French, sounding apologetic, shrugging and smiling as they gestured over the two corpses. I couldn’t make out what they were saying, but I could guess. Sorry, we found them like this. It is a shame for good boots to go to waste when we have so little.

Fair shot them. Two sharp cracks, a bullet each to the chest. They were both dead before the second shell casing hit the ground, bounced, and rolled to a stop.

“Fucking looters,” Fair said. He slung his rifle and moved the GIs off the road, taking a dog tag from each of them. They wore the same shoulderpatch as Fair, the red-and-blue 30th Infantry Division insignia. He gathered up papers and stuffed them inside each man’s jacket. Then he took the boots and watches from the Frenchmen, left a pair of boots next to each GI, and shoved the wristwatches into their shirt pockets. He stood for a moment, shaking his head slowly.

“It’s not right,” our driver said, his hands resting on the steering wheel. “Stealing from the dead. Especially when them boys are from our own outfit.” He sounded angry and apologetic at the same time.

“They were idiots, driving like that,” Fair said, stuffing the dog tags into his jacket as he returned to the jeep. “But no one has a right to take from our dead. Right, Captain?”

“You could have turned them over to the military police, Sergeant,” I said.

“What, and make you and your pal walk? Sorry, Captain, but I got my orders. No one loots our dead, and I take you to Bricqueville. So mount up.”

We drove on at a snail’s pace, past the dead, both the young and foolish Americans who had come to liberate France, and the old and foolish French who stole their boots. None of them expected to die today on this dusty stretch of road, but there they were, shattered bodies in a ditch.

“I don’t know if I would’ve shot them,” Big Mike said in a low voice, leaning in close. “But I wanted to.”

“Yeah, I didn’t like seeing them paw over our boys,” I said. Which was true enough. But I also didn’t like Sergeant Fair much either.

Maybe because he did what I, like Big Mike, wanted to do myself. It’s not pleasant to see the worst of yourself in another man, so I tried to think about something else. Like the dead body waiting for us down the road.

Dust means death. Like that line from Genesis that scared me back in Sunday school: For dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.

“Keep it slow,” I told the driver. “The dead can wait.”