Introduction by Timothy Hallinan

Cool and hot. Yes and No. Head and shoulders. Matter and anti-matter. Laurel and Hardy.

Sueño and Bascom.

Martin Limón has created my favorite crime-solving team since (and, perhaps, including) Holmes and Watson. He’s taken a perfectly balanced union of opposites and put them into a whole landscape of opposites. Army grunts versus Army brass. The rigidity and pragmatism of the U.S. 8th Army versus the truculence and tradition of Korean officialdom. On a larger scale, the permanent war between North and South Korea.

It’s in the intermittently neutral spaces between all these grinding jaws that Limón sets the stories in which George Sueño and Ernie Bascom right wrongs caused by crime, betrayal, stupidity, misunderstanding, prejudice, drugs, and heartbreak. This is American-occupied Cold War South Korea, long after the armistice that resolved nothing and long before the miracle explosion of the economy. So, in addition to all the other opposites in Limón’s books and stories, we have a vast economic and political division between haves and have-nots, between the powerful and the weak.

Martin Limon owns this world in a way that very few writers can claim their setting and characters. He learned it first-hand, over the course of a decade spent with the Army in Korea. Like George Sueño, he opened himself to Korean culture and learned the language. Like Ernie Bascom—who will walk through a wall when it’s the shortest distance between two points—he developed a healthy loathing for the cover-your-ass obstructionism of Army procedure.

So he had the experience to tell these stories. But hundreds of thousands of people graduated from that same school of experience, and none of them came up with George and Ernie. None of them came up with the AWOL soldiers in the Ville, none of them came up with the tragically exploited working girls, the Army’s boneheaded officers and lost boys, the hard-eyed Korean cops, the whole landscape of want and desperation, invisibly layered with a rich and deeply spiritual culture thousands of years old.

And that’s because Martin Limón is a writer of the very first rank. He’s a poet of the people, although without the political connotations that phrase might suggest. He looks at people of at least two cultures and at every level, and he sees all the way through them, and then he uses his gifts to put them on the page, so fully the reader feels that he or she can walk around them. And then, sometimes, he allows them to be broken into tiny pieces, and as we readers retreat to our fundamental conceptions of right and wrong and our comfortable certainty that right will prevail, George and Ernie’s investigation reminds us forcefully that in this particular world, that’s often not the case. Sometimes tiny victories are the only ones in sight, and sometimes you have to search even for those.

I discovered Limón when his first novel, the astonishing Jade Lady Burning, came out. I waited, often impatiently, for each succeeding book. It got to the point where all I had to do was open the cover to smell the charcoal cookers, feel the cold, see the eyes of the people—almost know what was around the corner—because the world Limón creates is so consistent, so thoroughly known, in a way that only the very best writers’ fictional worlds are. If you think of, say, a prose description of a street as the point of view of a camera that’s been placed there, Limón is one of those rare writers who could tell you instantly what’s behind the camera and what’s out of view to the right and the left. (He can do the same with the internal landscape of his characters.) I soon learned to put aside a big chunk of time when the new Martin Limón novel finally landed in my lap, because I wasn’t going to be home, or anyplace close to home, until I’d finished it.

When I set out to write my own books about the emotional and spiritual collision between two cultures, Martin Limón was my primary inspiration. In thinking about my books, I read Limón not for events or characters or tropes but for the particular wizardry with which he keeps the larger perspective in view even while he’s got his reader at the level of details. When we see a movie, we’re rarely conscious of the lens the director has chosen, even though it can have a huge impact on how we see the scene. For Limón, it seems to me, this ever-present awareness of a cultural gulf is the lens through which we view the action in his books and stories, and it brings everything into a very clear and specific relief.

I am not a short-story reader, so it came as a complete surprise to me when Soho told me this volume was in the planning stages. All I can say is that it’s a bonanza on the King Solomon’s Mines scale, probably the best news of my reading year. I invite you to read these tales slowly or fast or however you do it (I really had to take my time because they’re so rich and so many of them are so overpowering) and once in a while, ask yourself whether you know any other writer who could do what Martin Limón does here.

And if you think of one, send me his or her name.

***

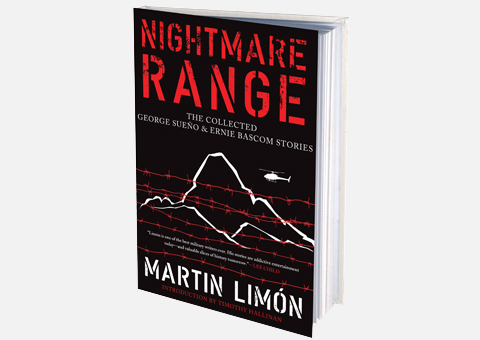

Read more about Martin Limón’s Nightmare Range.