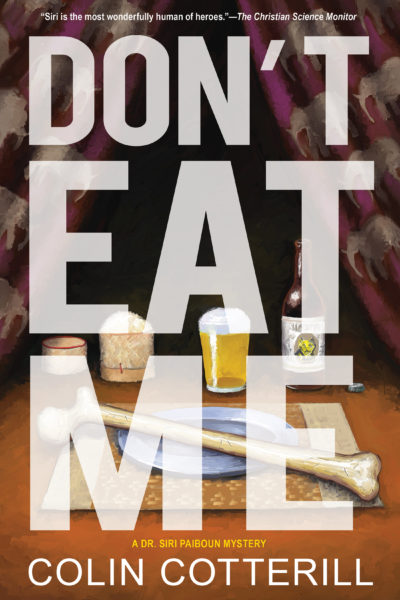

Colin Cotterill’s brilliant and darkly hilarious Dr. Siri Mysteries has its seventeenth installment publishing this month.

Don’t Eat Me follows the 75-year-old Dr. Siri Paboun as he attempts, among other things, to identify the skeleton of a woman that has appeared under the Anusawari Arch in the middle of the night.

Though the death of the unknown woman seems to be recent, the flesh on her corpse has been picked off in places as if something—or someone—has been gnawing on the bones. The plot Siri and his friends uncover involves much more than a single set of skeletal remains.

We asked Cotterill to discuss the book’s themes and ideas and how he went about setting them down on the page.

Enjoy!

1. What’s your new book about?

Don’t Eat Me is the latest in the Dr. Siri mystery series and, as usual, it looks at the political intrigues and mismanagement in the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos at the beginning of the 1980s. It deals with the lies that politicians can get away with and the advances that can be made with the right influential people at your back. But the underlying theme of the book is the trade in endangered wildlife and of what little importance it seems to hold in the eyes of the authorities.

2. What attracted you to the idea/concept of the book?

I’ve lived in Laos and Thailand for almost thirty years and I remember the days when you’d expect to find all manner of exotic wildlife at the fresh markets even in the cities. You could get tiger meat and medicinal extracts and pelts from creatures you’d see in the zoos of Europe and the Americas. Then, over time, as the world cries against cruelty and endangerment became louder, the creatures seemed to vanish from view. International organizations were reporting on national measures to restrict or ban hunting and dealing in wildlife. But I wondered how effective these measures had been. How much of the agreement was a cosmetic snow job to keep the foreigners happy? Laos and Thailand are both signatories of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) but what does that mean?

3. What kind of research was required?

Animal traffickers are very protective of their trade and go to violent ends to keep out nosey investigators. And there’s a lot of money involved so it’s still comparatively easy to bribe officials. I wasn’t likely to head off into the jungle with my machete to check out the reported illegal animal compounds. CITES has documentation of suspected dealings and I admired the workers who risked their lives to collate that information. As my Lao books are historical I needed to learn of the state of affairs in 1980. There had been no foreign journalists in the country for five years and there were no documented cases. I contacted a number of people involved in animal protection and they shared their personal knowledge and referred me to relevant material.

4. Which books or authors influenced you while writing this book?

Perhaps the most useful book I read in the lead up to Don’t Eat Me was The Animal Connection by Jean-Yves Domalain (1977). The writer was a supposedly reformed animal trafficker who knew the trade intimately and fell into a deep remorse over his involvement. He’d been the leading exporter of animals through Laos to the West for a number of years. He knew all the agents and which officials to bribe. The character Yves in my book is based on Domalain.

For a more recent update on what’s happening in Laos, I contacted Hanneke Nooren and Gordon Claridge and got hold of a copy of their book, Wildlife Trade in Laos: The End of the Game (2001). I wanted to believe it really was the end of the game but it turned out more of a case of a game developing from disorder to professional competence. As with the tiger farms in Thailand, the traffickers are moving away from the dwindling market in the jungles and into the world of battery farming. They’re getting smarter and better organized and a handful of Samaritan commandos isn’t going to make any headway against the industry.

5. Did anything not make it into the book that readers might find surprising or interesting?

When dealing with cruelty to animals it’s tempting to shock your readers with the gruesome facts and thoroughly depress them. I’ve written about child abuse and genocide in the past so I have experience of tempering my anger and getting on with the job of entertaining. So, to understand the vastness of the problem, all you have to do is multiply the horrors I’ve written about by a thousand and you’d still not be close to understanding it all.

There were two areas I downplayed in this way. Firstly was the role that zoos have played and continue to play in the decimation of wildlife. After reading Domalain’s book I would never go to a zoo or take my friend’s kids for a “wholesome day out.” The inmates you see there are the survivors; they’re the ones who somehow triumphed over disease and inhumane treatment and earned the right to see out their lives in environments that will make them miserable and kill them prematurely.

I was also light on the Chinese. It’s impossible to ignore the major role played by China, both as a producer and customer of wildlife products. The production of cures and life-extending remedies and aphrodisiacs—all with unproven efficacy—has become a multi-billion dollar industry.

6. When readers finish the book, what do you hope they will think and feel?

So, we get to the question, “What can I do about it?” Me? I can write a book and influence one young girl who will grow up to be a prime minister and enforce changes on the countries that ignore the regulations. Perhaps.

You? You could be angry for a little while until the story is supplanted by another cause from another book. But while you’re still moderately seething, join a group. Pick yourself an endangered species and fight for it. Politicians are more swayed by voter numbers than a well-written angry letter about the plight of the tiger.

For those of you who read the book and dismiss the treatment of animals in it as fiction, sadly, it’s not.

7. Have you seen any improvement in the treatment of animals in Southeast Asia as things stood in 1980?

No.

***

Excellent . . . The eccentric Siri continues to stand out as a unique and endearing series sleuth.” –Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

Buy from IndieBound | Buy from Barnes & Noble | Buy from Amazon | Buy from Soho Press