“What starts in a sanatorium leads to a high-stakes, dangerous race to find a killer and avert a crisis in the fight against Hitler . . . Chilling echoes of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Prisoner reverberate in every twist and turn of Billy Boyle’s life-or-death mission to unmask a plot in the thick of WWII.”

—Tom Straw, seven-time New York Times bestselling author writing as Richard Castle

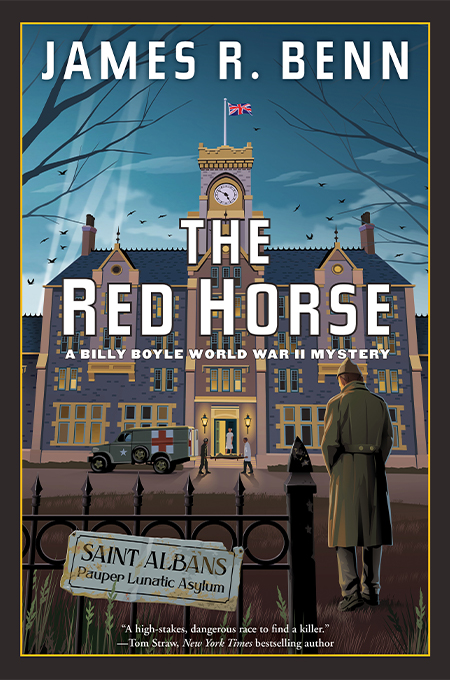

Just days after the Liberation of Paris, US Army Detective Billy Boyle and Lieutenant Kazimierz are brought to Saint Albans Convalescent Hospital in the English countryside.

They won’t have much time for rest though, because Billy is asked to help solve a possible murder at Saint Albans. The convalescent hospital is really a secret installation for those in the world of clandestine warfare to recover from wounds, physical and emotional. Some are allowed to leave; others are deemed security risks and are detained there. Billy must carry find the killer while maintaining his tenuous recovery, shielding his actions from suspicious hospital authorities, and dodging the unknown murderer.

CHAPTER ONE

Something was wrong.

The wind bit at the back of my neck, and I hunched my shoulders as gray clouds scudded across the sky, outpacing me as I trudged along the gravel path. I stuffed my hands into my pockets, thankful for the warmth.

Thankful I could hide the tremor in my right hand.

Because they were watching.

I couldn’t let them see how bad it had gotten.

My boots scrunched on crushed stone, the wide walkway stretching out before me. It looked like a straightaway, but the low wrought iron fence on either side curved slightly to the left. It was a circle. A long circle, but all the same, circles lead nowhere.

Which was where I was, evidently.

I don’t know why. I haven’t figured it out yet. All I know is that beyond the ornate fence, painted a gleaming jet black and hardly higher than my hip, there is another fence. In the woods, about ten yards in. A serious fence. Ten feet high and topped with coils of barbed wire. Patrolled by British soldiers who watched from the other side, silently staring me down.

I pushed on, trying not to attract their attention as they moved through the shadows beyond the wire. Two days ago, they’d let me outside. Not the soldiers, but the doctors, or nurses, or orderlies, or whatever they were. They said I could walk, that it might help me sleep.

But I can’t sleep a wink. Maybe that’s why I’m a little confused. Sometimes it feels like I can’t stay awake, either. Or move, for that matter. I didn’t want to go outside, but they insisted, so I started walking.

Two days I’ve been walking this circuit. My eyes are gritty with fatigue, but every time I stop to sit on a bench, my lids stay open. There’s a haze over everything—the woods, the guards, the massive stone structure constantly off to my left, its towers and turrets visible above the treetops and across the lush green lawns. My memory is hazy too. I don’t remember how I got here, although I recall waking up in an ambulance.

Before that, all I remember is France. Paris, to be exact. But everything is jumbled up, like in a dream, where things look familiar but nothing makes sense. I know this place isn’t a dream, because nothing looks familiar and nothing makes the slightest bit of sense.

It isn’t a dream or a nightmare. No, it’s worse.

Why?

The answer to that one was coming up ahead. The gravel walkway sloped downhill as it curved around the rear of the scattered buildings. I hadn’t even counted them all. There was the main building, four stories of sandstone set down in front of a green lawn, with a tall clock tower at the center. Wings extended off either end at right angles, like giant arms, encompassing a smattering of smaller buildings, all covered in the same sooty stone, soiled by the chimneys spouting coal smoke into the gray skies.

A service road cut across the path ahead. The gate was set in the woods, part of the security fence guarded by soldiers. I’d caught a glimpse of them a few times as they opened the gate to let in trucks bringing supplies. Their forest-green berets marked them as elite Commandos. I didn’t look in their direction anymore. They might think I was planning an escape.

Which might not be a bad idea if I knew where to go.

I quickened my pace as I passed the stone pillars that once had marked the entrance to the grounds. I could see the old metal sign that had greeted visitors; it was rusted and pitted by age, but still clear enough to announce what this place was.

Saint Albans Pauper Lunatic Asylum.

I was sure I’d been here before. I hadn’t seen the sign back then, but I’d driven through a back entrance to visit a British major. I hadn’t stayed long, but I knew this was the same joint. Except everything was different. Maybe because they’d let me leave that last time.

So, I know I’m at Saint Albans. About an hour outside London, if I remember correctly, not that my memory’s all that good right now. I do know I’m not a pauper. But there are some strange people here, and the place is surrounded by barbed wire and guards, so I guess it is some sort of asylum.

Lunatic? As I walked the path, I eyed the other residents. Or patients, probably. I tried not to make eye contact, not being up for a friendly chat. I saw the whistling man, an American who strolled the circuit regularly as he whistled a tune. The same tune. All the time. We passed each other, his eyes focused straight ahead and a little toward the sky, as if he were waiting for angels to swoop down and take him away.

I came to a Brit sitting on a bench. His wool cap was pulled down, covering his eyes. His arms were crossed and his legs jittered, boot heels keeping time. I’d seen him around. He was one of the mutes. Never spoke. There were a few of them here, all wearing the British battle dress uniform.

But that was all I could tell about them. Everyone was in uniform, but the rule at Saint Albans was no rank or unit patches. No identification, except for the color of your uniform. Last names only. It made sense, in a way. If the place was full of lunatics, it wouldn’t do for a crazy colonel to start issuing orders to loony lieutenants.

I picked up the pace as the path took me closer to the south wing. That was the medical area where people wore pajamas, bandages, and casts. They spent their time in bed, rolling around in wheelchairs, or limping about on crutches. I hadn’t run into any mutes or whistlers among them.

But I hadn’t been in the south wing in a couple of days.

I couldn’t handle seeing Kaz.

Lieutenant Piotr Augustus Kazimierz, that is. Kaz and I work together. We had some trouble in Paris and ended up here. I’m walking around and he’s not.

Bad heart. Really bad. My brain is sort of scrambled, but his ticker is shaky. He always had some sort of problem with it, which is why he ended up as a translator working in General Eisenhower’s headquarters. Kaz had been given a commission in the Polish Armed Forces based on his brains, not his brawn. But he’d built himself up, strengthening his body and using his brilliant mind as part of Ike’s Office of Special Investigations.

Until Paris.

Everything had fallen apart in Paris. Kaz’s heart, my mind, and, well, something else.

I can’t think about that now.

I pressed on, head down, not looking at the medical ward windows for fear I’d see Kaz looking at me. Wondering. Worried about his future and my sanity. I didn’t want to think about that either. Or that other thing clawing at the edges of my mind.

I walked faster, staring at the façade of the main hall now that I’d turned the corner. A few faces gazed out at me from the offices at the front of the massive building. Bored typists, doctors in their white coats, a few uniformed honchos, Yanks and Brits who gave the orders around here.

I made for the entrance, glancing up at the tall clock tower dead center. Ten minutes of five, but that time was only right twice a day. The thing was busted.

I stopped, uncertain if I wanted to go inside or take another tour of the estate. I stood there, rooted to the spot, paralyzed by the simple task of deciding if I wanted to go indoors. This sort of thing was happening all the time, and I didn’t like it much. Like I said, something was wrong.

I stood still, unable decide which way to go.

Which is why I saw the two men up in the clock tower. The door to the tower was usually locked and off-limits. They were nothing but blurs of brown uniform, heads and shoulders barely visible above the crenellated stonework as they scurried around, circling the white flagpole with the British Union Jack flapping at the top.

Then there was only one man, and he was flying.

CHAPTER TWO

He must have been a mute, because he made no sound.

Until he hit the ground.

The sound of boots pounding gravel snapped me out of my stupor. I ran toward the body as the front door slammed open and people tumbled out. White coats, uniforms, and suits. Behind me, a couple of guards were making a beeline for the body.

I got there first. I pushed aside a Yank in his unadorned khakis and a Brit major in his service dress uniform.

“Don’t touch anything,” I said. “I’m a police officer.”

Why the hell did I say that?

I knelt by the body, my mind a jumble of thoughts as I studied the dead man. Sure, I’d been a cop before the war. I’d even made homicide detective before I traded blue for khaki. But why did I announce myself like that?

Maybe it was the situation. People had a habit of rushing into a crime scene and obscuring what evidence there might be.

“Sure, you’re a policeman,” one of the guards said, his hand grasping my shoulder. “Now come along.”

“Wait a minute,” I said, shaking his arm off and raising my hand. He stepped back, and I could see his palm resting on the butt of his holstered pistol. It was a typical pose, putting enough space between us so he could draw his weapon without me grabbing it. I took my time, studying the corpse, committing everything I saw to memory. I may have had a few screws loose, but I knew what was what when it came to murder. Or suicide, maybe.

“Okay,” I said, rising and taking a few steps back, my hands raised slightly, apologetically. I didn’t want to risk being pistol-whipped.

“Get these patients away,” the major snapped, sparing a moment to frown in my direction. He was a thick-faced guy with a brown mustache and a stiff gait that seemed to pain him. Or he didn’t like his mornings ruined by patients falling from great heights, I couldn’t really say.

I gave the guard a friendly nod to let him know I wasn’t going to cause any trouble. I let him pull me back a few steps as his partner gathered the other Yank and an older Englishman in his darker khaki wool serge. As the major stood over the body, one of the white coats knelt and felt for a pulse. Purely for the record.

One other white coat stood aside, watching me. Maybe I was paranoid, or a lunatic, or both, but it was odd that he spent more time looking at me than at the guy who’d taken a swan dive onto packed gravel. Beneath his white jacket he wore captain’s bars on one collar and the caduceus of the medical corps on the other. He wasn’t a stranger. Captain Theodore Robinson, US Army psychiatrist. Blond hair, glasses, and an athletic build. Track star in college back in Wisconsin, he’d told me. We’d had a few chats, which consisted mainly of him yakking because I didn’t have much to contribute. But the army paid him anyway, he said, so I sat and listened. I’d been bored, but the army paid me too.

Robinson’s gaze finally wandered to the body. Mine went up to the clock tower. Nobody was leaning over, distraught at not being able to stop this guy from falling. I looked at the main entrance, where by now, the second man would have burst through, telling his story of trying to talk the jumper out of his fatal leap.

Nothing.

“What do you think?” I heard the major say.

“We’ve been worried about Holland for a while, haven’t we, Dr. Robinson?” This from the British white coat. Older than Robinson, gray showing at his carefully trimmed temples, dark bags under his eyes, and a thin, sharp nose that made him look like a sparrow hawk.

I didn’t hear Robinson’s response as the guards ushered us inside. I thought about saying something about the other person I’d seen up in the tower, but I was low man on the totem pole around here, and I could end up in a padded cell if I spouted off to the wrong person. Like the guy who’d tossed poor Holland to his death.

Or, I was imagining things, and then they’d put me in a straitjacket for sure. My best bet was to clam up and keep my head down. I let the guard shove me inside, resisting the impulse to unleash a smart-aleck wisecrack and give him a chance to kidney punch me when no one was looking. He wore sergeant’s stripes and a mean grimace splashed across a face in need of a shave. A private trailed us, Sten gun at the ready, looking angry enough to squeeze off a few rounds for the hell of it.

“You guys been at it long?” I asked, once we were inside and the door slammed shut behind us.

“At what, Yank?” the sergeant said as his companion stood by the door.

“Guarding this place. Patrolling the perimeter, that sort of thing.” I was going for polite conversation to learn anything about their routine, but the grizzled non-com wasn’t going for it. “Have you been on duty all night?”

“Yes, while you’ve been dreaming of Betty Grable, we’ve been tramping through the woods to keep you safe, lad. Now go on, leave the business outside to the major. He knows how to handle these things.”

“Okay, Sergeant,” I said. “I didn’t catch your name.”

“Didn’t give it, but since I know who you are, Boyle, seems only fair you should have it. Sergeant Owen Jenkins,” he said.

“Well, Sergeant Jenkins, I’m flattered. What do you know about me besides my name?” I asked, wondering if it might be something that was news to me.

“You like to walk,” he said, taking one step forward and fixing his dark eyes on me. “And you’re not friendly, not the way a lot of Yanks are. Most of you lot talk too much and too soon, if you don’t mind my saying so. Not you, though.”

“The conversation in here isn’t to my liking,” I said. “Maybe if we met in a pub we’d get along better. What’s the best watering hole around here? Or are you new to the area?”

“New?” Jenkins said. “Why’d you say that?”

“With all the fighting in Normandy, this must be like a rest area for you fellows,” I said. “What do they do, rotate you in for a few weeks of easy duty before you head back to the front? You can’t be stuck here permanently, can you?”

“Next time I see you, Boyle, best walk the other way,” Jenkins said, his finger stabbing my chest. So much for making polite conversation. I didn’t think a tough British sergeant would be so sensitive. “Or you’ll be here, permanent-like.”

“Come on, Sarge,” his private said, walking to a window and glancing out front. “He’s tetched in the head, remember? Pay him no mind. They’re taking the stiff away, so let’s go have a smoke.”

“Bastards,” Jenkins said, apparently taking in me and everyone else in residence at Saint Albans. “Living easy while our lads are fighting and dying. Leastways you and the others without any wounds. It’s one thing to be shot up, but where’s your wound? You’re nothing but a coward in my book.”

He turned on his heel and marched out the door, slamming it against the wall.

“Don’t say anything, sir, willya?” asked the private, glancing at the open door as he whispered. “Sarge is a bit on edge, is all.”

“Don’t worry, kid,” I said, looking more closely at him. His wool field service cap was pulled low over his eyes, but it didn’t disguise the fact that he had no worries about a five o’clock shadow. “Who would believe a nutcase like me anyway? What’s your name?”

“Fulton, sir. Private Martin Fulton.”

“Okay, Fulton. Now tell me something and I’ll keep this all under my hat. How did your sergeant know my name? Are you watching me during the day? Keeping tabs on me?”

“No, that’s not our job. Sarge asked that big fella who was here the other day, the Yank sergeant. He said you were a captain and that we should watch out for you, that’s all.”

“So you are watching me. Thanks, Fulton, now get back to your bully boy pal and stay away from me. Get it?”

Private Fulton’s face worked itself into a twist, as if he couldn’t understand plain English. He shook his head and walked away, muttering. Watch out for me, he’d said. Spy on me, more like. Jenkins, Fulton, and others, I bet. I’d have to watch them.

And have a talk with Big Mike. There was no reason for him to go around spreading rumors. He was supposed to be my friend. Some pal.

I heard a flurry of voices from outside. It sounded like Robinson and the others were at the door, about to enter the foyer. I darted into a hallway, not wanting to draw attention to myself or answer any questions. My bootheels were loud on the tiled floor, and I scurried as quietly as I could to a small alcove in the center of the hallway. On a stairway, the walnut banisters gleamed brightly, polished by countless hands over the decades. Next to the stairs was a door, an engraved sign proclaiming it to be the entrance to the clock tower. no admittance.

The door was wide open.

It was as good as an invitation.

I shut it behind me and walked up the narrow staircase. The stone steps were worn, and my footsteps echoed as I made my way, wondering what was going through Holland’s mind as he took his final steps. How had he gotten in? I knew the door was kept locked or was supposed to be.

Perhaps someone had been working on the clock, or doing some other repair job, and left the door open. I stopped to catch my breath, took a gulp of air, and kept going. I could picture a workman panicking as he saw Holland at the top of the tower. Maybe he tried to bring him back down and Holland fought back. Maybe it was an accident. If so, the workman might have hightailed it, trying to avoid any blame.

Or, was Holland murdered? Was that what Jenkins meant when he said I might find myself here permanent-like?

I came to the top of the stairs. I opened the access door and stepped out. The Union Jack snapped loudly in the breeze above my head, startling me. The space was smaller than I’d imagined, taken up by beams that held the flagpole in place and the thick stonework of the battlements. I walked around, looking for a trace of evidence as the wind whipped at my face. Up here, the breeze would carry away any loose bit of fabric or paper.

Had Holland left a note? Probably in his pocket. That’s where jumpers stashed them sometimes. I leaned over the edge, looking down at the spot where he’d landed. A small darkening stain and scuffed stones were the only vestige of Holland’s final act upon this earth. Who was he anyway? What demons delivered him here? And down there?

From this vantage point, I could see the attraction. Vault over the wall and in seconds you’d have not a care in the world.

I could also sense the fear. The trembling fear of being pursued, unable to speak, his voice tamped down into the darkest corner of his mind, cornered and pushed against the hard, cold stone.

Hands grabbing him and hoisting him over.

The scream silent inside his head.

“Boyle.”

I jumped. Not like Holland, but I jumped, my heart thumping at the surprise.

“Step away from the wall, Boyle,” Robinson said. “Let’s go to my office and have a chat.”

“Sure,” I said, walking around the flagpole, keeping my distance. I’d learned one thing, anyway. Dr. Robinson was light on his feet.

CHAPTER THREE

“Have a seat, Boyle,” Robinson said. There was a couch in his office, but that seemed too melodramatic, so I took my usual spot in a worn leather armchair. Robinson had changed out of his lab coat and wore a nicely tailored Ike jacket. It fit his trim body well, which I guess was one of the benefits of having been a track star. As for the tailoring, that told me he had good taste and cared that people noticed. It occurred to me that I might already know more about him than he knew of me.

Robinson picked up a pen and pad from his desk, sat himself in a straight-back chair, crossed his legs, adjusted his glasses, then looked at me. The man took his time getting settled, but maybe it was part of a psychiatrist’s routine. It gave him time to observe me, even while he fiddled with his pen.

“Why are we here?” I asked. “Couldn’t it wait until two o’clock?” That’s when we had a session scheduled.

“The army calls that 1400 hours, Boyle. You’re an officer. A captain with Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force.”

“Yeah. I work at SHAEF. So?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said, flipping through his notes. “I guess I find it odd that after more than two years in the army, you haven’t picked up on the standard issue lingo. Now, I do see guys who count on their fingers to figure out the twenty-four-hour clock, but they do it. You, on the other hand, are one smart guy. It must take more mental effort to not say 1400 hours than to simply give in to it.”

“It takes five syllables to say it the army way. Three to say it the normal way.”

“See what I mean, Boyle?” Robinson said, tapping his pen on his pad. “You’re a sharp fellow. Intelligent enough to try to distract me with a wisecrack and not answer the question.”

“Listen, Doc, if I’m calling in an artillery barrage, I’ll say 1400 hours to be sure they don’t deliver twelve hours too late. But around here, two o’clock will do just fine, see?” I felt myself on the edge of my seat and eased back into it. “So, make your point or let’s call this quits.”

“Take it easy, Boyle. Only making conversation,” Robinson said, sounding like me when I talked to Sergeant Jenkins. We were both fishing for something useful. “It must have been a shock to see a person leap to their death.”

I shrugged.

“You must have seen worse in combat,” Robinson continued.

“It was different,” I said. True enough. People wearing the same uniform usually refrained from killing each other. Not all the time, though, which was one reason I was in my line of work. I crossed my legs, matching Robinson sitting across from me. I tapped my fingers on my thigh, as he was doing with his pen and paper. It was a trick my dad taught me to use in interrogations. Match your posture and movement with the suspect, and he might open up more easily under questioning.

“Why do you think Holland jumped?” I said, scratching my jaw as he rubbed his.

“No idea,” he said. “What I’m more interested in is why you’re mirroring me.”

“Is that what you call it?” I said, laughing despite myself. “All I know is that it’s an old detective’s trick. My old man swore by it, but I never knew if it really worked.”

“It can create the impression you and the person you are conversing with have things in common. And it’s a two-way street, since by adopting the other’s pose, you may begin to feel empathy for them. I can see it would be useful in getting a suspect to cooperate. But does that mean you feel I’m a suspect?”

“You’re keeping me locked up,” I said, trying hard not to avoid his eyes. That would be a dead giveaway that I was lying. It could have been him up there. Not in the white doctor’s coat, of course, but he could have discarded it.

“You have the run of the place,” he said, spreading his arms wide. “That’s hardly locked up.”

“What if I wanted to go into town? Those Brit Commandos would drill me dead, no questions asked, if I ever made it over that barbed-wire fence. I can’t leave, and that’s locked up in my book.”

“Commandos? Drill you? You’re overreacting, Boyle.”

“Hey, there must be a town around here somewhere. Want to go for a beer, Doc?”

“No. I don’t,” he said, scribbling in his notebook. “Tell me, why did you say you were a policeman? Outside, when you approached the body.”

“Holland,” I said. “That was his name, right?”

“Yes. Thomas Holland. Now, why did you announce yourself as a policeman?”

“Force of habit,” I said. Robinson waited, so I took a breath and gave him the basics. How my dad and uncle were homicide detectives with the Boston Police Department. How I’d followed in their footsteps. I left out the part about getting my promotion to detective mainly because a copy of the exam had found its way to me the night before I took it. And how Uncle Dan was on the Promotions Board. People who weren’t part of how things worked for the Irish in Boston had a hard time understanding that sort of thing. It was our department, our city. Back when an Irishman couldn’t get an honest day’s work, being on the cops meant a steady job for you and your own. It meant something, something this blond track-and-field star from somewhere in the Midwest would never understand. Maybe his granddaddy from the old country might, but not this corn-fed all-American.

Uncle Ike? I didn’t go anywhere near that story. Then they’d really think I was bonkers.

“You came upon a sudden death and your police training took over, is that it?” Robinson asked. I think he’d been talking for some time before that, but I’d been lost somewhere else. Back home.

“Yeah, yeah. Are we done yet?”

“One more thing. Why did you go up in the tower?”

“Scene of the crime,” I said. “I was still thinking like a cop.”

“Crime?” Robinson said.

“A head doctor ought to know suicide’s illegal,” I said. “Or were you thinking of something else?”

“I had a shock when I saw you at the edge,” Robinson said, ignoring my question.

“Is that why you followed me up there?” I asked. “You were worried about my state of mind?”

“That’s my job,” he said. “But I didn’t know it was you. I saw the door was open and wanted to be sure no one else had wandered up there. It’s kept locked for a reason. It’s a hazard in a place like this.”

“The door was open when I came to it,” I said. “But I shut it behind me. So, how’d you know anyone was up there? Or were you following me?”

“By open, I meant unlocked,” Robinson said. “Do you think people are following you, watching your every move?”

“You said one more thing. That’s two. See you later,” I said, as I rose and made for the door.

“What happened in Paris?” Robinson said, his words like a dagger at my back. I froze, my hand on the doorknob. I couldn’t turn it. My body went rigid as sweat trickled down the small of my back, the wood grain of the door swirling before my eyes.

I felt Robinson place his hand on mine, and together we turned the knob. With his other hand on my shoulder, he gently pushed me along into the corridor.

“I’ll see you at two o’clock,” he said, and shut the door behind me.

“Fourteen hundred hours,” I whispered. I laughed, even though I couldn’t figure why it was funny.

I headed for the south wing. Time to see Kaz, like it or not.

I crossed the foyer and spotted the English gent I’d seen earlier, the older fellow who’d been shooed away along with me and the other Yank. He was cracking open the door carefully, as if afraid of what he might find.

“Hello,” I said, tapping him on the shoulder.

“What? Oh, you gave me a fright, young man,” he said, turning his face toward mine. His unkempt hair was black and flecked with gray, his shoulders slumped, his eyes downcast over a pair of spectacles perched on the tip of his nose. He looked more like a professor than a soldier, and I wondered how he’d ended up in this joint.

“Is the coast clear?” I said, giving him a conspiratorial wink.

“You mean our minders, do you? Yes, they’ve cleared off,” he said. “Along with poor Holland.”

I pushed the door open, holding it for him as a stiff breeze blew over us. “I’m Boyle,” I said, keeping to the local custom of last names only.

“Sinclair,” he said, taking the steps carefully, like a man twice his age.

“Did you know Holland?” I asked, as we stopped by the spot where he’d fallen.

“Know him?” Sinclair said, as if the question startled him. “Of course not. No one knows anyone here. Secrets, that’s all there is here. And when there’s nothing but secrets, no one knows a damned thing!”

Without another word, Sinclair turned away from the small pool of drying blood and walked to the pathway, taking small, careful steps. He sounded nuts, until I thought about it. Whatever this place was, he’d figured it out. It was a house of secrets, and odds were, with Holland in the morgue, at least one secret was safe.

For now.

Intrigued? Purchase The Red Horse here!