Aimée Leduc isn’t done prowling the cobblestone streets of Paris, but for the past decade I’ve had another story I’ve needed to tell and can wait no longer.

Aimée Leduc recently celebrated her twentieth anniversary (nineteen books in twenty years is hard even for me to believe) and I’m thrilled to confirm—she will be returning. I’m writing this in Paris where I’m researching her next adventure. So far, as a private detective, Aimée has investigated murders in eighteen of the twenty Parisian arrondissements. Soon, she’ll be entangled in a yet-to-be-named arrondissement. There are only two arrondissements left for Aimée to adventure in. Any guesses?

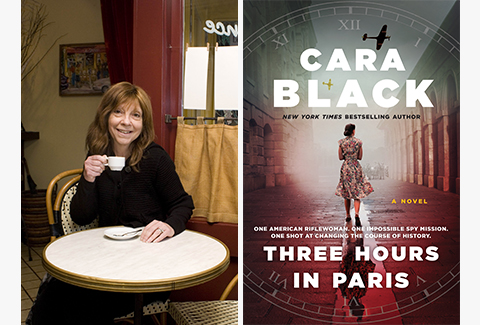

It’s not that I wanted to stray from my Aimée Leduc series, but rather that there was a story I had to tell. This story, Three Hours in Paris, germinated and grew from information and anecdotes I encountered during my many research trips to Paris. Before long, I found myself thinking about it as often as the Aimée book I was already writing at the time. But I waited. A few more books passed while Three Hours in Paris sat on the back burner.

I’ve always been interested, maybe a little obsessed, with the Second World War era. Tales of the war and military service were handed down in my American family. In France, I began to visit the battle-scarred sites I’d previously only read about. To this day, I am still deeply impressed by the Parisian buildings with bullet holes left from street fighting during the Libération in 1944. The war is very much still visible in Paris and so my WWII story was always lurking in the periphery.

Somewhere along the way I began keeping a separate journal to jot down ideas and note stories from older Parisians I spoke with. I began saving period photographs and old maps I’d find at the flea market. I consulted with private collectors of WWII memorabilia and interviewed former Résistants whose memories of the German occupation still contained a freshness and pain that was startling. It wasn’t until I found myself poring over archival newspapers and documents that I realized that Three Hours in Paris was the only book I could possibly write next.

As I said before, this story had long been on a slow boil, simmering, while I wrote the Aimée Leduc investigations. Now that the story was out in the open, I was excited to actively work on it. My heroine even had a name: Kate Rees. Kate, I was soon to learn, lived a hardscrabble life during the Depression. She was motherless, the only girl in a family with five brothers, and learned to survive while moving around Oregon with her father, a migrant ranch foreman. Her father taught her to shoot game and defend the ranch, a necessary skill in backwoods Oregon. Her family’s itinerant life made her resilient. Kate, I decided, descended from the frontier women. She was forged in the Wild West. A cowgirl.

A modern young woman in her time, Kate came from all the strong, even headstrong, women I’ve ever known. She is very different from Aimée in many ways: more stolid in character, more solidly built in appearance, and decidedly less fashionable. But fans of my Parisian detective will find these two women definitely share moxie, spirit, and relentlessness.

While Kate Rees was surprising as she developed, I already knew the fulcrum on which her story turned. The seed from which she and this novel grew was a single historical fact, a footnote really, that was irresistibly full of potential. In June of 1940, after Paris was seized by the Nazis, Adolf Hitler came to Paris to victoriously survey the city. He spent only three hours in the City of Light before abruptly leaving and never returned.

Why did Hitler leave so quickly? What could cause him to flee from a city held in the Reich’s iron grip? From this little imaginative exercise in “What happened?” came the opportunity to finally tell the story of occupied Paris and weave together all the lore I’d been hoarding.

In 1940, Germany invaded France. Paris was declared an open city to prevent its destruction, though it reeled during the first two weeks of the occupation in June, 1940. Many Parisians fled in an exodus to the countryside and what passed for the hastily re-assembled government operated from Bordeaux. Rationing was on the horizon and a curfew was put in place by the occupying German command. Historians sometimes refer to this period it as the honeymoon phase. The German soldiers, Luftwaffe, High Command and staff were under strict orders to behave. And enjoy. This was Hitler’s gift to his troops after they had blitzkrieged across Europe. Hitler was also resting them. Operation Sea Lion, the name for Germany’s plan to invade Britain, had already been drawn up and stamped for approval.

Enter newly appointed Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who’d rallied his country to save their troops at the ignominious retreat at Dunkirk. He saw the writing on the wall: his island country was next. Churchill desperately needed a win. It would have to be incredibly bold to give his country confidence in what he, not to mention Britain itself, could accomplish. For that, he relied on the little-known Section D. This branch, the precursor and forerunner of SOE (Special Operations Executive), was mandated to run sabotage operations and assassinations in Occupied Europe. All Section D operations were clandestine, often using non-British agents, not officially sanctioned and therefore deniable. No love was lost between Section D and the British Secret Intelligence service who thought of them as a seat-of-the-pants, put-together-with-spit outfit of misfits. Just what Churchill needed.

Several of Section D’s files became unclassified a few years ago and fell into my purview. These amazing documents reveal a rough-and-tumble outfit of men—and some women—with skills as diverse as their backgrounds. Class, family and elite old school ties didn’t count here. This group was recruited for their abilities to think on their feet and outside of the box.

Back to our Kate. This tough girl from the American West went to Europe. She married a Welshman and together, they had a child. She found herself living life as a European woman. Until a German bombing took all of this away, leaving Kate bereaved and then, enraged. Gifted with a skill for languages, a knowledge of how to live off the land, and not least of all a way with guns, the grieving Kate would be recruited by Section D. A woman like Kate Rees, a markswoman who’d lost her husband and child to the enemy, desirous of revenge and without anything to lose, was exactly the sort of outsider Section D looked for.

Kate was just the woman this novelist needed to send the Führer packing and spring the story I’d been longing to tell.

All of this is to say: I had to do this. To my dear Aimée Leduc fans, I want to reassure you that as I write this note, our gal in Paris is already on her way back to bookshelves. In the meantime, I am hopeful you will enjoy the story of Kate Rees and occupied Paris half as much as I did writing it.

—Cara Black